Water Music II: Dotcom Dolphins

For the first part of this essay, see here.

IV.

With its positing of hardware as wetware, Vaporwave could efficiently stress just how much the economic system it is classically concerned with – late 20th century capitalism – was founded on liquidity (avoiding a certain landmass chauvinism), and haunted by the underwater. To Vaporwave, all consumer products might as well be wet, and all interesting culture is partly submerged.

And of course, all the ‘satirical’ bite Vaporwave develops also derives from this; from its incessant tracking of what happens to 1980s and 1990s water music when it sinks down beneath the water line, and performs its superficiality below surface. This is promise degenerated, submarine echoes of water-top extravaganza, disembodied pleasure, dark, hollow – but promise degenerated is still promise. The rumor of a king’s existence might be even stronger underwater.

Where you turn on the screen, the shore begins.

Simultaneously, its close association of hardware and wetware rendered the interface between ‘computer culture’ and what is commonly referred to as wetware – organic nervous systems including, for example, the human CNS and the brain – more permeable. In the classic view, organic systems are called wetware on the grounds of the large role that water plays in organic matter; but to Vaporwave, the same was true for 1990s hardware. Wetness was not the point of differentiation, but the common ground between the digital and the organic. Now the point of Vaporwave was not to claim, for example, that the Internet had a consciousness (that would be closer to a cyberpunk idea, I guess), but to be interested in the narco-agency of digital information; that is, what happens to the human nervous system in the situation of information impacting it immediately; immediately insofar as wetware interacts with wetware. Does this not amount to a sort of hydrophilic shock?

What has been called the hypnagogic aspect of Vaporwave is a result, I think of this interest. The hypnagogic side of Vaporwave speaks of the association of digital culture and non-ordinary states of consciousness, especially sleep and dreams. There is a fascination with PlayStation menu soundtracks, and especially with the PSX startup sound (1994), which is this great electronic double-impact sound – a spacey opening-up-sound followed by something like a deep blast – that fades away accompanied by a glissando of chimes and what I would describe as a synthetic reed-sound. There you already have something not unlike Water Music heard underwater, with this amazing combination of dark deep ominous soundscape sprinkled with sparks of glitter and brilliance; and I think it is crucial to note that the higher sounds are imitations of instruments while the sonorous double-impact is ‘openly’ electronic, without any pretense of imitating something else: rather, it seems to dramatize the way in which the screen opens up into this abyssal deep sea of digitality. Equally a source of vapor fascination is the PS2 menu sound (2000), which is, and I guess nobody will be surprised, an Ambient track, consisting of little more than what could be called gushes of electricity, readable as wind passing through trees, but equally readable as waves hitting the shore. Again, where you turn on the screen, the shore begins; and what appears on the screen is a strange type of jetsam. But the PS2 menu sound is of such strong interest to Vaporwave especially because it plays as long as the menu is left open, which allows for the hypothetical situation of you falling asleep at some point, and then waking up, and because you didn’t really plan to fall asleep you’re all confused and the world seems slightly off and you don’t know what time it is, but there is still this swooshing sound coming from the PS2 and it makes everything very tranquil and calm and eerie, and you’ve basically entered a different plane of reality at this point, a plane of wonder and terror, and it is really tied to the endless repetition of distant waves crashing in your living room. The temporal disjointedness of this moment – the way you feel as if with your unplanned nap you nestled yourself into a fold of time, into some obscure temporal pocket – is essential and already alludes to all those vapor doxa thinkpieces on the connection of Vaporwave to lost futures and nostalgia for things that never were etc., but more low-concept and closer to the point I’m trying to make is saying that what happens here is, first of all, that the sounds work with something like occasionality drag: how, as I’ve briefly remarked earlier, occasional music drags something of the occasion with itself even when jolted out of it.

Vaporwave takes these sounds – the PSX startup sound and the PS2 menu soundtrack – as data, as historical indices, as sites of libidinal attachment, and as proof that the Dotcom sublime is submarine in character. But it is also telling how neither of the two sounds really found their way into the vapor sample catalogue – they have been sampled, yes, but in no way as often as their prominence in vapor discourse could suggest. In different ways, both sounds are already too self-conscious, too theoretically advanced – they’re almost blueprints for Vaporwave rather than ‘raw material’.

Both the PSX startup sound and the PS2 menu music are occasional music, sounds for a specific setting, accompanying a particular process or situation. But menu music exhibits something like a sprawling occasionality, because the duration of the occasion is wide open – it takes place as long as you choose to stay in the menu – and thus lends itself to a seemingly endless repetition for when you never actually start up a game, or when you shut down a game but then not the console; and when listened to long enough, or returning to listening to it after having fallen asleep, it seems as if it had turned into something else, as if its ‘setting’ were no longer simply the menu interfacing you and your game library, but you and the deep sea. The occasion has sprawled, the menu music ‘still’ fits. It is Water Music ready to become Underwater Music.

The PSX startup sound is different as it is tied to a specific length, and a specific pattern of repetition: It repeats every time you start up the console, and it always takes up the same amount of time. But within this short timeframe, it dramatizes its underwater side by employing these dark, slowed-down samples in connection to the shimmering glissandi. It is Underwater Music employed as Water Music, and although this is a fascinating moment historiographically speaking, it is almost too advanced for Vaporwave, which is more interested in Water Music as Water Music, in order to establish, on its own, the respective Underwater Music. Rather than as something to be sampled, the PSX startup sound is something to be striving for.

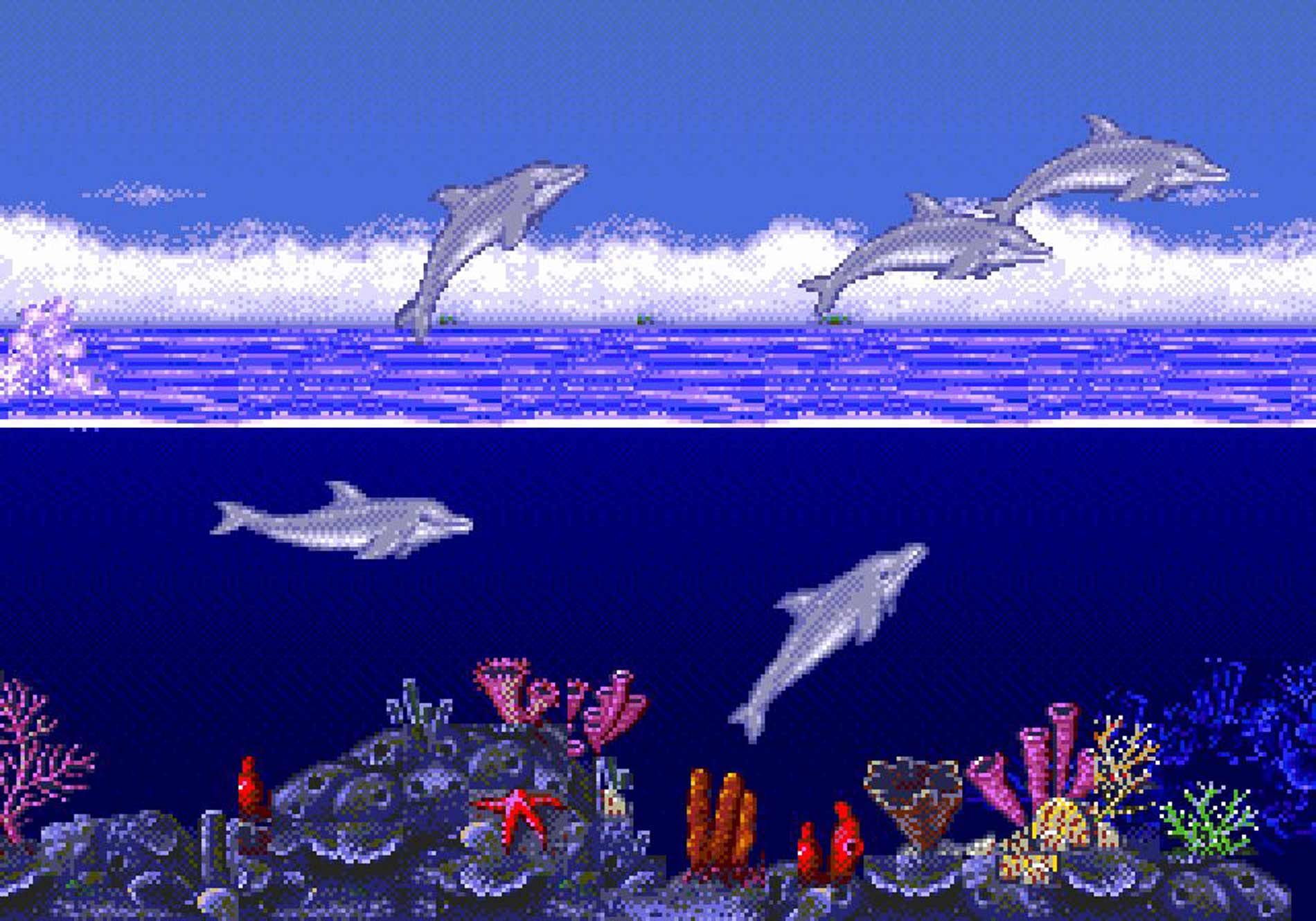

A similar interest is directed towards underwater levels in videogames. After having identified hardware as wetware, Vaporwave had to regard underwater levels in videogames as meta-levels: A basic truth about digital culture reaching visual density. Rather than as plugging in or jacking in, Vaporwave conceived of entering ‘cyberspace’ as a form of diving in. Underwater levels literalized and visualized this; so it was only logical that Vaporwave would be interested in the acoustics of underwater levels. What kind of sounds did the 1990s consider suitable for those instances in which it brought its hidden substrate to the foreground? I have already mentioned how Eccojams Vol. 1, a foundational album for Vaporwave, has to be read specifically, that is to say, taking the particular choice of game seriously. It is not enough to say that early Vaporwave was interested in game soundtracks. No, it was interested in the soundtrack of a very specific game, or at least of a very specific type of game, namely Ecco the Dolphin, which took place underwater. As mentioned, you play a dolphin, and a lot of the gameplay is based on sound and feedback: By pressing a button, you emit song – and thus communicate with other marine animals, but by pressing the same button for just a little bit longer, you make the sound waves return to you, and by doing so gradually establish a map of the level you play.

But while all underwater levels had the aspect of manifesting the marine quality of 1990 cyberspace, the choice of Ecco the Dolphin (rather than another game taking place mostly or exclusively underwater) might have another reason still. More than any other game of the era, it made the connection of 1990 digital culture and the submarine explicit, by alluding to an ever so slightly obscure figure at the intersection of (1) sound and acoustics, (2) the underwater, (3) global communication networks, and (4) narco-agency.

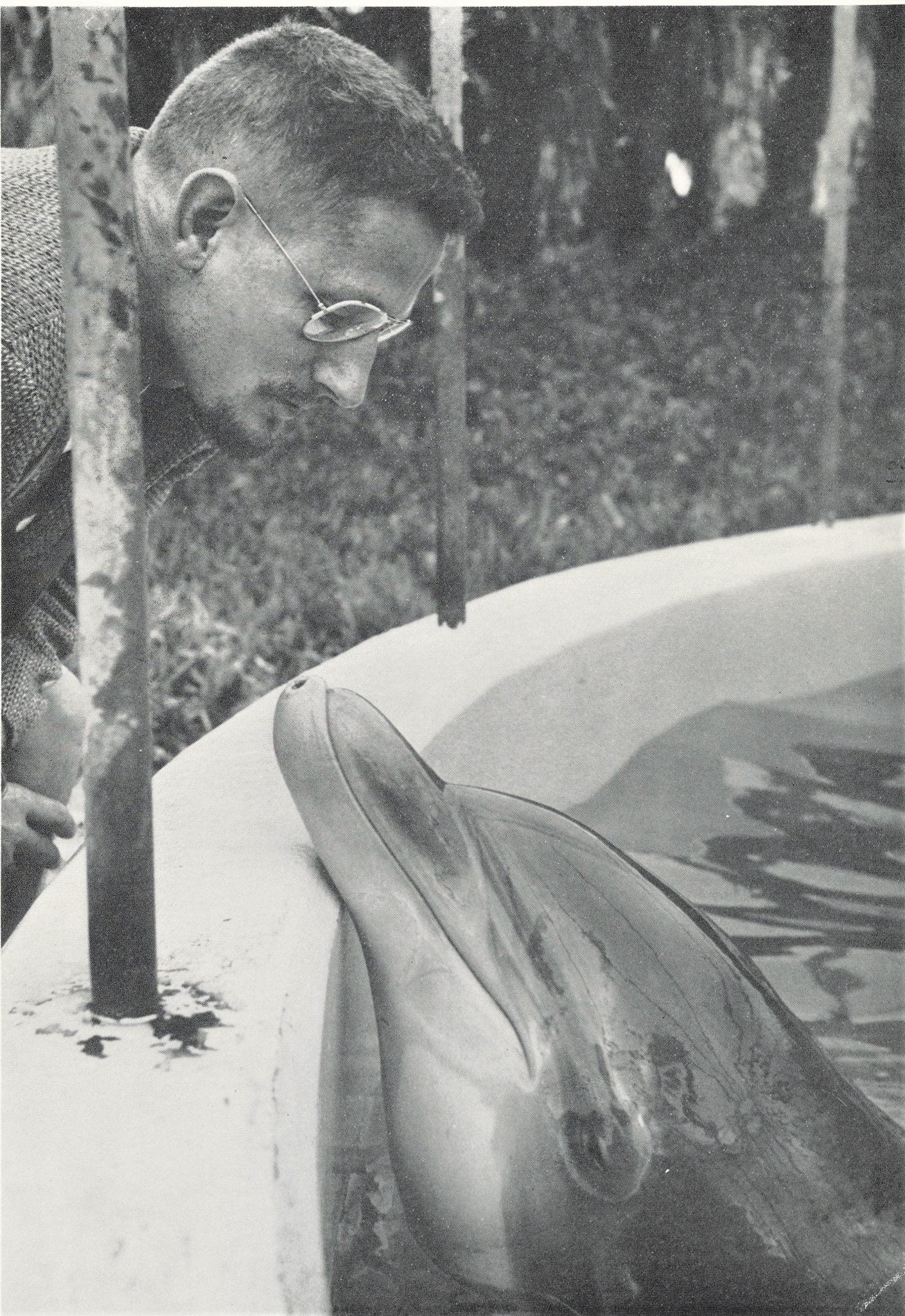

Of course, Ecco is also and openly fascinated with submarine machines and submerged technology (including cables), but the core motif is really and simply the dolphin: Inevitable, here, to not think of John C. Lilly and his bizarre scientific trajectory, which led the neuroscientist from an interest in dolphin bioacoustics to an interest in human-dolphin communication to an interest in higher planes of consciousness; and all the way down to the ketamine-fuelled conjectures, everything about him might just be peak Dotcom progeny, except filtered through the 1960s (or not yet filtered through the 1980s, as you prefer).

In the shortest of summaries, Lilly was convinced communication between humans and (the far more intelligent) dolphins would be possible if only humans would reach the sheer elegance, intensity, and speed, of submarine sonar information transmission, and he was equally convinced that this would require only some reprogramming of human wetware. Drugs were meant to help, and also those flotation tanks he constructed, in which the human body laid suspended and submerged in water and darkness (breathing through an oxygen mask), entering some algae finesse of reception and thus the dolphin plane of perfect long-distance communication (recall the hypnagogic aspect of Vaporwave). To him, plugging in meant diving in.

Whenever he managed to overhear dolphin conversation, Lilly said, the onslaught of maximum-intensity communication always overwhelmed him.

And he produced endless amounts of tape, obsessively recording both his scientific notes and his conversations with the dolphins.

Did I mention that all of this happened in California? Oh, and at some point, he put the lower floor of his beach house under water in order to let a dolphin live there. Talk about a sunken living room.

Once, while suspended in his flotation tank (“dolphin world”), Lilly claimed, two extraterrestrial visitors visited him. (Alien visitors would always choose dolphins to talk to, because they’re Earth’s most intelligent species, so it was thanks to him being in dolphin world that he was approached). They told him about a secret worldwide organization of extraterrestrial origin, reigning over and regulating chance on earth. They were called the Earth Coincidence Control Office, or E.C.C.O. for short.

This is very weird, but perhaps it renders something else a bit less weird, namely that the enemies in Ecco the Dolphin are extraterrestrials. Perhaps.

Since the time of Lilly’s experiments in the 1960s, he has become something of a mildly obscure meme, and is regarded as a quaint precursor and prophet of technological and media obsessions of the 1980s and 1990s (which are, in case it needs to be said, the obsessions that Vaporwave returns to); as an early proto-Dotcom guru with a Beat-type counterculture vibe.

In 1995, the lead cyborg of tape loops, Laurie Anderson, released a song in honor of his work and his obsessive use of tape; while in 1998, the cult-classic SF Anime Serial Experiments Lain riffed on Lilly’s conception of dolphin communication as a global network of soundwave-based information transmission. It makes a lot of sense to place Ecco the Dolphin within these 1990s works that spoke about (or alluded to) Lilly’s work, and what Eccojams Vol. 1 does is saying that just like Anderson’s song and the Anime, the game cannot speak about Lilly without speaking about 1990 media. These are all instances of 1990 technology showing its submarine colors, its underwater genealogy.

So when Eccojams Vol. 1co-founded Vaporwave, it did so by claiming that just as this game is speaking of the Internet by speaking about an underwater world, in turn, speaking of the Internet would mean speaking of an underwater world.

V.

Ecco the Dolphin, then, provided Vaporwave with a shortcut into the circuitry of communication systems, sound, narco-agency, and the submarine.

Yet videogame underwater levels also featured another aspect of interest to Vaporwave, namely a specific sort of stress; a stress that springs from an intersection of a certain tranquility and a certain terror. Many of the comments under the YouTube videos to the PSX startup sound and the PS2 menu ambient debate whether those sounds are soothing or scary, calm or terrifying. The answer, of course, lies in the simultaneity of those affects, the combination of tranquility and terror. Recall the idea of waking up after a sudden nap and hearing the PS2 menu music that had droned on all through your sleeping; the disjointed temporality of this moment could well be accompanied by a slightly disgusting feeling and an almost-hidden, partly submerged dread. Waking up from that unplanned nap will always feel like waking up too late and too early at the same time. And remember how the PSX startup sound performs an eerie simultaneity of Water Music and Underwater Music, of the sparkling glissando and the abyssal blast.

Fittingly, the creator of the startup sound, Takafumi Fujisawa, has spoken of his work in explicit terms of security and catastrophe:

“My aim is to lead the sense of security when the console is turned on to the excitement after with the C major dominant motion showing the intention for continuing to be on the mainstream, the rich strings kick in and the last part features twinkling tones and setting the perfect 4th chords. The function of this sound is to tell the user that the hardware is running like it is supposed to, and that the disc has successfully been read. To add, the swooshing reverse sound is designed so that it can go into loop if the disc couldn’t be read, and we can understand if something went wrong.”

The way in which underwater levels dramatized this simultaneity was by establishing a turquoise tranquility, and the dreamlike physics of moving underwater – often a heavy change in feel from the overwater levels within the same game – but then imposing some sort of deadline, classically in the form of an oxygen limit that forces the players to punctuate said tranquility with a rhythm of coming back up to draw a breath. As a result, underwater levels feel both more relaxing and tenser at the same time. In games with no oxygen limit to their underwater sections, enemies to fight or avoid added danger to what, in other conditions, would be only calm aquatic ambience; enemies that, moreover, were made more menacing by the typically low visibility of underwater levels. With characteristic (por)poise and precision, Ecco the Dolphin featured both: Although it takes place almost entirely underwater for obvious reasons, the choice of a dolphin as protagonist meant that the player would still be required to come up for air from time to time. Combined with the fact that the ocean is swarming with hostile fauna (and with the last level of the second game in the series, a level called “Welcome to the Machine”, which no longer takes place in the ocean at all but within a huge and labyrinthine industrial structure that has, tellingly, exactly the same physics as the ocean, and features increasingly terrifying alien monsters), this has led several commenters to claim that Ecco the Dolphin is actually a horror game series.

VI.

The machine that is the underwater – the hardware that is wetware – is characterized by an cohabitation of tranquility and terror: it has taken me a long detour to make this point, but I suspect it is an essential point with regards to how exactly Vaporwave is an Underwater Music.

As 1980s and 1990s Water Music slowly went under, sinking down beneath the water line, the way the water filtered and mixed the sound rendered something about them visible, unleashed something, that was ever so slightly uncanny, eerie, or downright disturbing. Glitches uncovered the tension inherent to stadium pop anthems or guitar licks from TV commercials; the intermixing of samples from different origins favored strange mutual commentary; the empty happiness of muzak gradually stressed the emptiness rather than the happiness; promises hollowed out. Disembodied sounds quoted a water-top world that might no longer be there at all, sounds reaching fish ears like light from a dead star. And finally, as sound was no longer transmitted through air, but through water, it gained a packed, dense, stifling quality.

Take, as a quite blatant example, Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five’s “The Message”, a track both expressing and inducing pure anguish, but which then was used as the soundtrack of e.g. a Lacoste commercial and a SUV advertisement. A true yet trivial thing to say would be that this shows how capitalism is able to make itself the occasion of everything (and turns everything into at least latently occasional music). But Vaporwave is not about making just that kind of trite point; rather, what it is interested in is how just as “The Message” is hollowed out by these occasional repetitions, something of its anxiety flows over into the commercials, and some of the commercial’s promise (“You too can be beautiful”, “You too can be safe”, etc.) back into the song, and it is that libidinal intermingling that produces the mix of promise and anguish, futurability and despair, that results in Blank Banshee’s “Teen Pregnancy”. But a more salient example might be how the opening track of Eccojams Vol. 1 discovers absolute stress within Toto’s saccharine ballad “Africa”, as a rampantly glitching soundscape harbors the incessant repetition of only the line “Hurry boy she’s waiting there for you”: Again, this is the dreamlike stress of waking up after an unplanned nap, maybe with a single sentence full of nondescript urgency (who is “she”? Where is she waiting? What do I have to do?) ringing in your head, and the PS2 menu soundtrack droning on in front of you. The Kafkaesque aspect of all of this is not something Vaporwave adds, but uncovers, as Toto’s Water Music sinks down towards the River Thames floor: the “Hurry boy”-line is there in the original song, and famously, the song itself was inspired by a UNICEF documentary about starving children in Africa, which neither the slightly dumbfounded mawkishness of the song’s lyrics nor the all-out extravaganza of the instrumental exactly gives away, but which, like an archeological layer, Vaporwave uncovers as a punch of impossible urgency towards an immense task.

VII.

Let me pause here and summarize. What I have tried to describe is how all Water Music gradually sinks down into the water it first floated on top of, and on its way down, like a whale carcass slowly sinking towards the ocean floor, disintegrates; and Underwater Music is this swarm of a million large, small, and tiny animals picking away at that large carcass of sound, filtering, gnawing, dissecting, regurgitating, digesting. In the case of Vaporwave, everything starts from the thesis that all hardware is wetware and that Dotcom culture is, thus, partly submerged, so the body of water Water Music sinks into is the Internet. There was other Water Music and Underwater Music before, but only with the advent of digital culture, the phantasm of a recording ocean received an actual technological dispositive. Since the Internet exists, it functions as the type of submarine world Water Music sinks down into.