Baloo, or, Bear With Malabou

So, we probably should talk about Cocaine Bear, but we should not talk too much about it. A success in the US, Cocaine Bear is a strange, but not so rare case of an overproduced B-movie, slasher and lowbudget animal feature imitation. The story, based on some however true events (we probably should at some point also talk about what Hollywood has done to « true events », how it has produced them and willed them into historical existence, but we should do so without any reference to Baudrillard whatsoever, just to make him sad), ‹depict› a bear which, after having consumed cocaine, gets addicted and extremely aggressive while everyone around it seems to become more stupid in the same degree, addicted to some sort of idiot-plot-oriented, narrativized ‹retardedness› oder medievality. My friend summarized the movie perfectly: « It is too well made to be trash, but not funny enough to be good. »

I immediately realized that there is something libidinal about the confrontation of these two agents - bears and drugs -, when I was able to watch it cramped inbetween kids and Christian businessmen on an airplane while the bowels of a park ranger got splashed over the screen. The « cocaine bear » is unnecessarily violent and kills park rangers, hiking hippies, police, ambulance and drug lords alike, all in the search for more white powder, which it is going to share, although accidentally, with its cubs in the end. The movie is straightup annoying and pretends to be trashy, and this makes it hard to critize it (as Barbie); but something is specifically hysterical (in the old and sexist sense of a libidinal suppression) in the imaginable giggles the producers might have had, when briefing the writer's room with an animal ‹getting high›, as they would probably put it, on drugs. But it is not « drugs », it is - oddly specific - cocaine, a Zurich high functionality upper. As I have learned in the meantime, in « Krackoon » from 2010 racoons attack a Bronx town after developing a habit for crack.

After the movie has ended, I picked up the book I had been reading before. « Croire aux fauves » by Nastassja Martin, a short essay - but it is too well written, too well narrated to be an essay, it is fiction - about her being attacked by a bear, when she was on research in Siberia. The bear broke her jaw and ripped two teeth out of her face, it bit her in the leg and she countered it with an ice pick. But the story does not center so much on the incident than on the events that followed it: How medicine treats or abuses her, how people start to explain her « accident », defend or insult the bear, how they pity her for the destroyed face, and how all these explanations and societal reactions interfere with her anthropological research on animism and the idea of the Other, nature.

In reasonings that might be dangerously similar to traumatic responses, Martin relives the event, she wonders if she did not in fact choose the bear, if there was not some conscious decision that made her do it, but she decisively claims the bear chose her, the bear and she interacted in a way that bound them together so that she became bear-like herself and that she is living with the bear as it is living within her. In this she seems to develop a sort of addiction to the bear and its surroundings, she leaves France again and returns to the Evenes in Siberia because she cannot live without meeting « it » again. This might be an all too comfortable lesson in post-humanist animal studies, were it not for the sudden realization she has when confronted with the Evenes: They might be better equipped to manage the incident, by calling her a miedka, half woman, half bear, and explaining nature not from the perspective of humans alone, but by considering different agents. But in their idea of a signifying third, of a nature that made the bear « letting her live » and returning her back « as a gift » to them, they still cannot account for the contigency of the event. It is symbolically overloaded and in her disgust with all these explanations, while of course always returning to them, she tries to find an understanding that accounts for the insularity and nothingness of the encounter, which at the same time meant so much to the bear and the human in the aftermath, in the very physical inscription of the event, in her jaws, in his flanks. This book is, disregarding some more metaphorical and forcibly poetic verbalisations in the end, an extremely clever and - by way of its form - a very apt way to add to the new materialisms. She finds, in Malabou's sense a « plastic » form, a form that is capable of giving and taking form at the same time.

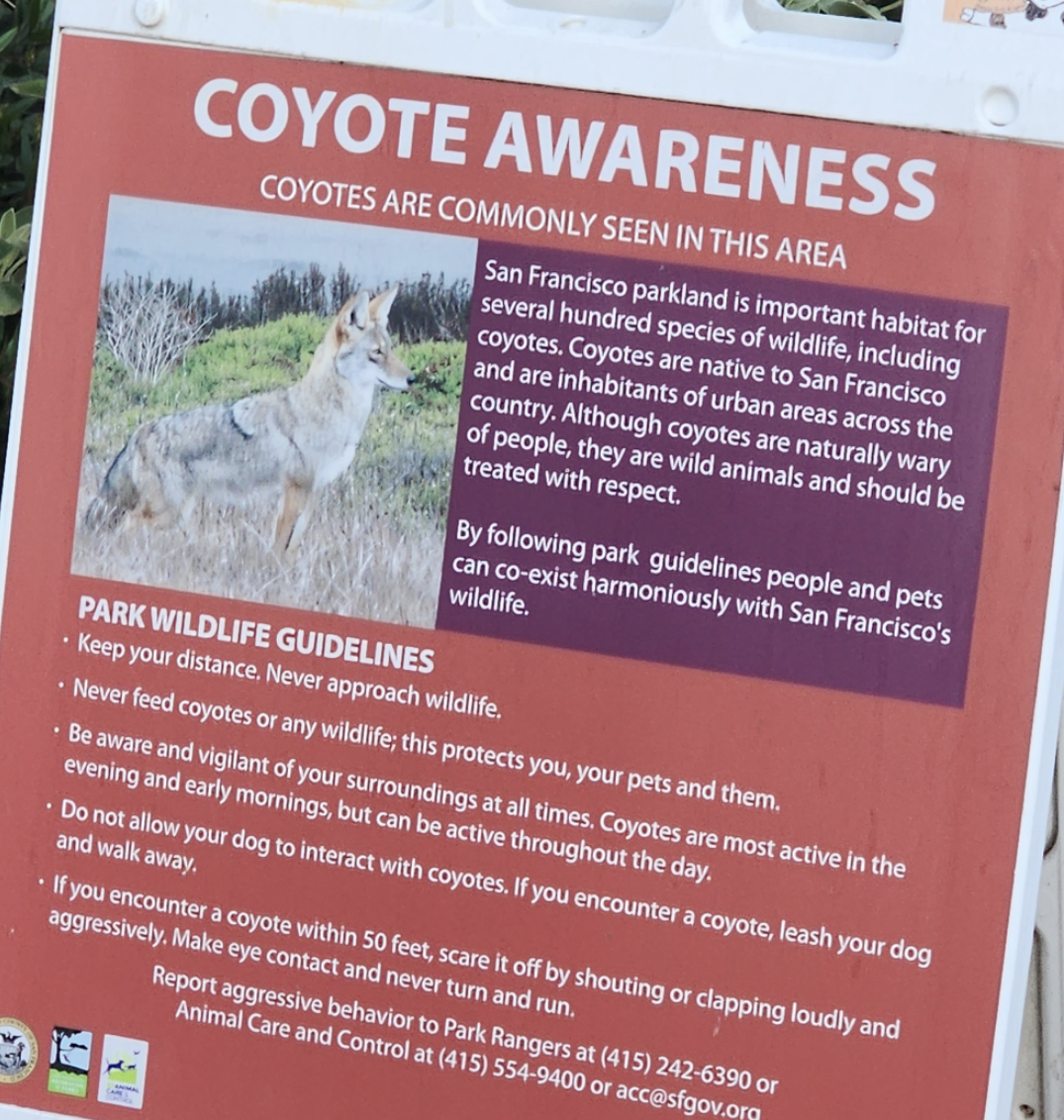

Leaving the plane, I get around San Francisco, the city often claimed to be most affected by the Opiod crisis. At least, the explosive killing streak of Opiods might have been stabilized at around 80.000 deaths in 2021 and 2022, but 2023 will show. Fentanyl is mixed with many other drugs, and is in turn sometimes substituted for the cheaper Xylazin, which is a horse-tranquilizer. « The National Safety Council calculated that the lifetime odds of dying from an opioid overdose (1 in 96) in 2017 were greater than the lifetime odds of dying in an automobile accident (1 in 103) in the United States. » (And back in 2017 only 50.000 died from opiods). But what I rather see than junkies, like some stupid European with Baudrillard's « Symbolic Exchange and Death » on their lap, is ads. Smokey bear waving from a billboard, drugged eyes, telling me only I can prevent what is devilishly called a « wildfire ».

Malabou is herself interested in what direction the new materialisms, for example her own account of the speculative realism, will further lead. « Wither Materialism? », is one of her papers titled in which she intends to ask « Where is materialism currently going? Is materialism currently dying? »

In Darwins natural selection - the « whole organisation seems to have become plastic », he writes -, Malabou sees the plasticity of nature in place:

« The form ‹takes› when variabilty encounters natural selection. Natural selection transforms the contingency of the former into a necessity. […] In nature, the fittest is never the one that accidentally falls upon a favourable environment for its survival. It is a matter of simply ‹adjust[ing] a response› to the environment, to restate it in François Jacob´s terms. A'aptation, the agreement between the environment and variation, can of course be unpredictable. » [Whither Materialism, 208]

By this reading of Darwin, that is very much in line with her interest in evo-devo and epigenetics, she wants to update Althusser's search for a real Marxist materialism. According to Althusser's « The Underground Current of the Materialism of the Encounter » (1982) there are two materialisms in Marxism at work: First, the « materialism of necessity and teleology; that is to say a transformed, disguised form of idealism ». Second « an almost completely unknown materialist tradition in the history of philosophy […] a materialism of the encounter, and therefore of the aleatory and of contingency. » [203]

A materialism of the contingency sounds almost exactly like that what Martin is looking for, and her philosophical argument certainly is based on an ecounter. The problem is that in society Darwin's principles rarely occur because any plastic form here tends to be institutionalised and therefore pre-selects its selection criteria. This is also the problem of the symbolic that Martin encounters after the encounter when everyone explains to her the ‹bear event›: « The automaticity and non-teleological character of natural selection seems definitvely lost in social selection. […] Is not the materialism of the encounter always doomed to be repressed by teleology, anteriority of meaning, presuppositions, predeterminations? » [207]

Even in Marxism the suppression of the encounter occurs: For Althusser, there exists no such thing as the proletariat as a product of a capitalist class (this would be « the logic of the accomplished fact of the reproduction of the proletariat on an extended scale », as he writes, « a very great piece of nonsense »). Rather the capitalist mode of production arose form an encounter between the « owners of money » and « the proletarian stripped of everything but his labour-power. » This encounter « took place, and ‹took hold› », it became an « accomplished fact ».

While Althusser seems to use the word « encounter » relatively emphatic, for Malabou it is just the possibility of death (or other forms of being naturally de-selected): The encounter is not something good in itself, it is a jaw ripped apart, but also it is the only encounter from which capacity is possible.

In another piece she links this idea of an encounter with the other as plasticity to drugs and addiction: «The brain maintains itself in its changing environment by becoming addicted to it, understanding ‹addiction› in the proper sense as a ‹psychotropy›, a significant transformation or alteration of the psyche. » She mentions this to counter the dilemma that a new materialist history wants to dethrone humans in historiography, but also needs to explain the beginning or the « interruption » of consciousness; she finds a solution in the brain as the medium that turns the human into a « geological agent pure and simple», in Charkabarty´s sense. « Human practices alter or affect brain-body chemistry, and, in return, brain-body chemistry alters or affects human practices. Brain epigenetic power acts as a medium between its deep past and the environment. […] Addictive processes have in large part caused the Anthropocene, and only new addictions will be able to partly counter them. »

Narcoleptic and tired of my own addictions, I had been hesitantly watching the Hulu series « The Bear », too, about a run-down restaurant owner (restaurant and owner, yes) in Chicago. I watched, numbed of tv show addictions, in microdoses, very pleased, very unexcited. Even there, the neurotic US relationship to drugs is performed, mediated by movies which in turn have their own logic of addiction (we will never forget angelicism01´s piece on The Queen's Gambit): For some unclear reason, Carmy who worked as haute-cuisine cook in some of the toughest restaurants, never does coke and only goes to anonymous gatherings to speak about his dead brother. « If he did have alcohol issues, I feel like they would have shown us », someone writes (in a thread with a picture of Carmy´s arm tattoo depicting a bottle of alcohol).

Maybe he didn't want to end like his brother who was an addict. As the protagonist of one of those new « moral » and « woke » tv shows that many like to crictize, but which create quite spectacular imaginations, he has the attitude of a bad boy without being bad, the appearence of being destroyed without lacking the resources to verbalize his fears and to do some care work, really, really unimaginable, or better: a fantasy; the attitude of the addict without being addicted to anything (but the pressure of the kitchen).

Accounting for addictive brains, Malabou sees a new mentality forming in the Anthropocene, the « narcolepsy of consciousness ». The addictions of the brain release the human subject from the grip of human control and consciousness and they materialize a longer form of time than just the phylogenesis; she speaks in wake of Braudel of a historic « mentality » rather than a « consciousness », the « mental » not the « neural ». Addictions create material « embedment » (Malafouris) inscribed in the material of the brain while preserving humans as agents, even though they are now geological or global agents, acting within their material network. The narcoleptic addiction, caused by indifference and numbness, sound of course not like a good thing when it comes to managing the geological catastrophe. But Malabou also sees something good in it, first because it is appropriate: «the type of responsibility required by the Anthropocene is extremely paradoxical and difficult to the extent that it implies the acknowledgement of an essential paralysis of responsibility »[199]. Second, because it supposes a new collective subject in the term « a new mentality, that is, new addictions, new bodily adaptions to an inorganic and earthly corporeity, a new natural history ».

In the city center among the Fentanyl corpses, staring into a paralized Smokey Bear, thinking about the cocaine-abstaining cook of the Bear who is addicted to work, but only in a good way, we can imagine what the Cocaine Bear adds to the mix: First, it's the bear that takes the drugs and releases the pressure on the humans to be addicted: Seeing the bear recalibrating its so called « genetic programming », by the sheer ontological void of psychotropy, by the white powder material that gets from outside into its body and alters its neural network, I cannot help but think, that this is what Nastassja Martin is looking for: If the bear was as addicted to her as she was to him (because she needed him to repair the brutal contingency everyone wanted to compensate with symbolic meaning), it would not be a question of human mentality but of a bear mentality, of being bearish (« characterized by or associated with falling share prices »). Very much like the unaddictive movie which you only watch further when you have a bearish disposition: the bear gets more addicted, the less you are. Second, it is an upper, not a downer: Cocaine, not Fentanyl. Getting wild, not narcoleptic; and not getting agency or pulling yourself together, as a workaholic does. The bear is high - very opposite to baloo's bare necessities - and he uses his material embededness not as a form of weakness (e.g., in the defensiveness against a changing environment in climate change), but as a form of overcoming its own limitations, becoming the thing some people have always feared he already might be (a killing beast).

Martin's book by its interesting form, is a much better fit to describe the plasticity in encounters between a bear and a human: how both of them get connected, how contingent and both meaningful and meaningless it is. Martin wants to retrace the mentality that is created by the natural selection of both and gets paralysed. But Cocaine Bear offers at least a clear-cut alternative mentality to the paralysation and narcolepsy of the geological human, and let's us wonder what would have happened, if « Croire aux fauves » was about a bear on a trip. Maybe the only real reason for humanity in the post-Anthropocene is for nature getting high on them.