So unhappy happy easter!

The third season of "LOL: Last One Laughing" Germany has just been released on Thursday, and it's really hard to put the finger on what is interesting about it. But the Japanese reality game show, in which comedians are not allowed to laugh for six hours straight, is intriguing and irritating and very fitting to be released on the mourning "Good Friday" (but then again I have an inexplicable, opaque interest in most competitive game shows).

[ spring is the saddest season to laugh, and you do. :( ]

The setting reminds of class rooms on Friday afternoons in which the teachers tried to silence an imbearable desire to break into laughter. They, of course, failed almost all of the time and here, of course, it starts to get interesting. As our society is so rigorously structured by laughter, I always wondered why Foucault does not mention it as a disciplinary technique. Contrary to what it may seem on a Friday afternoon in school, laughter, even the seemingly uncontrolled one, is part of the teaching. (That's why I never trusted the Bachtinist take on the carnevalesque subversion of it.)

Laughter is important for the collective desires, it is surreal in its own terms.

[ insert Zizek on canned laughter, the Lacanian take on Sophokles, "Illusionen der Anderen" and Lynchs horrific "Rabbits" (2002) in which canned laughter is detached from any semantics of the sitcom: as millennials who we are after all, this is all too familiar. :( ]

Laughter is key to the most important zeitgeist emotionalities of the past decades - the 90's cool, the "this is fine"-depression of millennials' memes, the awkwardness paradigm etc. - and it structures release&attack of almost all cultural interactions (except on Zoom-sessions in which muted mics created the eerie atmosphere of a crowded and laughterless void). But there is no Bergsonian vitalism in it and no Freudian release kitsch ("Abfuhr seelischer Erregung"), it is an instrument of phatic control, to dampen interaction, to soften awkwardness, to make oneself pleasing and harmless.

[ correspondingly, the absence of "laugh tracks" in sitcoms has become a common horror meme, showing the verbal brutality and abusiveness of early 2000s TV. :( ]

"LOL" is in many ways complicit with this structure: Laughter is canned (the laughter comes from the off - the drop-outs behind the studio are, sadly, cut over the laughterless interaction in the arena) and, by convention, the suppression of laughter by the actors is what TV comedy and improv makes funny in contrast to stand-up comedy where laughter is a crucial tool of the rhetorics, often timely and virtuosly enacted by the comedians themselves.

But it breaks with the structure of laughter, too, as it installs a different regime of laughter discipline. Here, comedians are deprived of their most important currency of recognition, humour is getting annihilated by every chuckle and every LIQ (laughing-in quietly), the other important physical reaction the title of the show implicitly refers to. This deprivation of artistic appreciation is cruel in ways not often seen in TV. (And one wonders: What if writers didn't receive the nodding of their elder audience, what if philosophers couldn't count on the glowing, somewhat aggressive, somewhat admiring eyes of the ones they provoke (thought-provoking, the currency they wish to receive).)

What's interesting therefore is not the fight for the best jokes and the competitive character of comedy.

[ we have seen this already in the aggressiveness of roast battles, traces of which have become a pre-slap institution at the Golden Globes and Oscar awards :( ]

It is the micro-genealogy of humour within the six hours of the new regime that shows us stages of progression and regression of humour in a lab setting. A humour evolution and devolution en miniature.

The first seconds appear to be some of the most difficults - the reenactment of the class room, everyone is struggling to not burst out in laughter while there is apparently no reason to do so: It is the laughter of the antihumour, of the no-reason-to, the toughest obstacle to keep yourself together. After that, some will try to use their professional skills, they give witty answers or perform stand-up pieces from their repertoire, it starts getting sophisticated for one hour or so, just to turn - and this is probably the most interesting phase - into a maddening, excruciating mood where different stages of deterioration break through: the well-tempered witty joke is rivaled by slap stick, practical jokes, stupid puns, screaming, absurdist performances. It gets annoying and physically grinding. After that, in the sixth and last hour, it becomes what comedy without laughs always has been: a horrific extermination of sense.

The third season of german LOL has a peculiar twist to it that matches the horrors of easter: As one of the participants, Mirco Nontschew, has died in December 2021, the show is haunted by several zombies bundled up in one person: first, the body who is struggling not to laugh while it is already dead - negating the vitalism of Bergson again, he was the last one laughing as he was also the first one to drop out, for which he "died" in the game logic and was, secondly, sent to the after-life backstage that is allowed to burst with laughter. Third, Nontschew is a surprising revenant in the comedy scene. Having been one of the more successful comedians of the 90s, his practical comedy which involves The Mask-like grimaces is old-fashioned at best - he is not the only one to represent a forgotten or extinct humour as the host Bully Herbig, who built his 2000s reputation on homophobic and racist jokes he virtuosly intertwined (Der Schuh des Manitu, 2001), makes obvious. (As the participant Carolin Kebekus puts it after first meeting another contestant: "Den gibt's ja auch noch". Most of them had their bloom in the 2000s, the high noon of stand-up comedy.)

LOL is only mildly funny, but it is a fascinating showcase of how the clash of humours from different ages, which are as shockingly incompatible as is their fashion, and the experimental setting, in which a mini-evolution of humour is taking place within an ecosystem that does not reward it (at least not with the common currency of laughter), turns into an otherwordly, creepy zombie-environment.

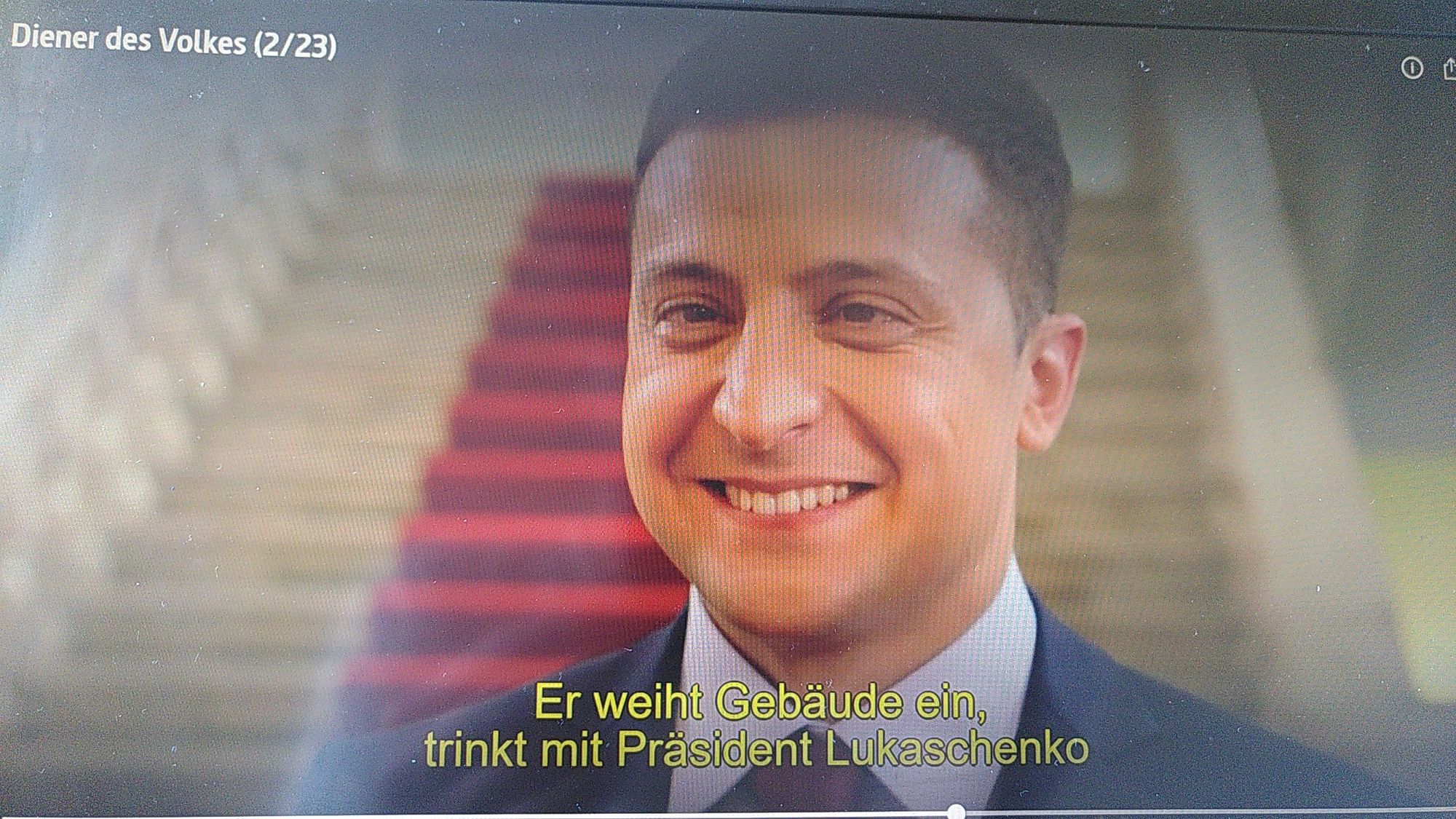

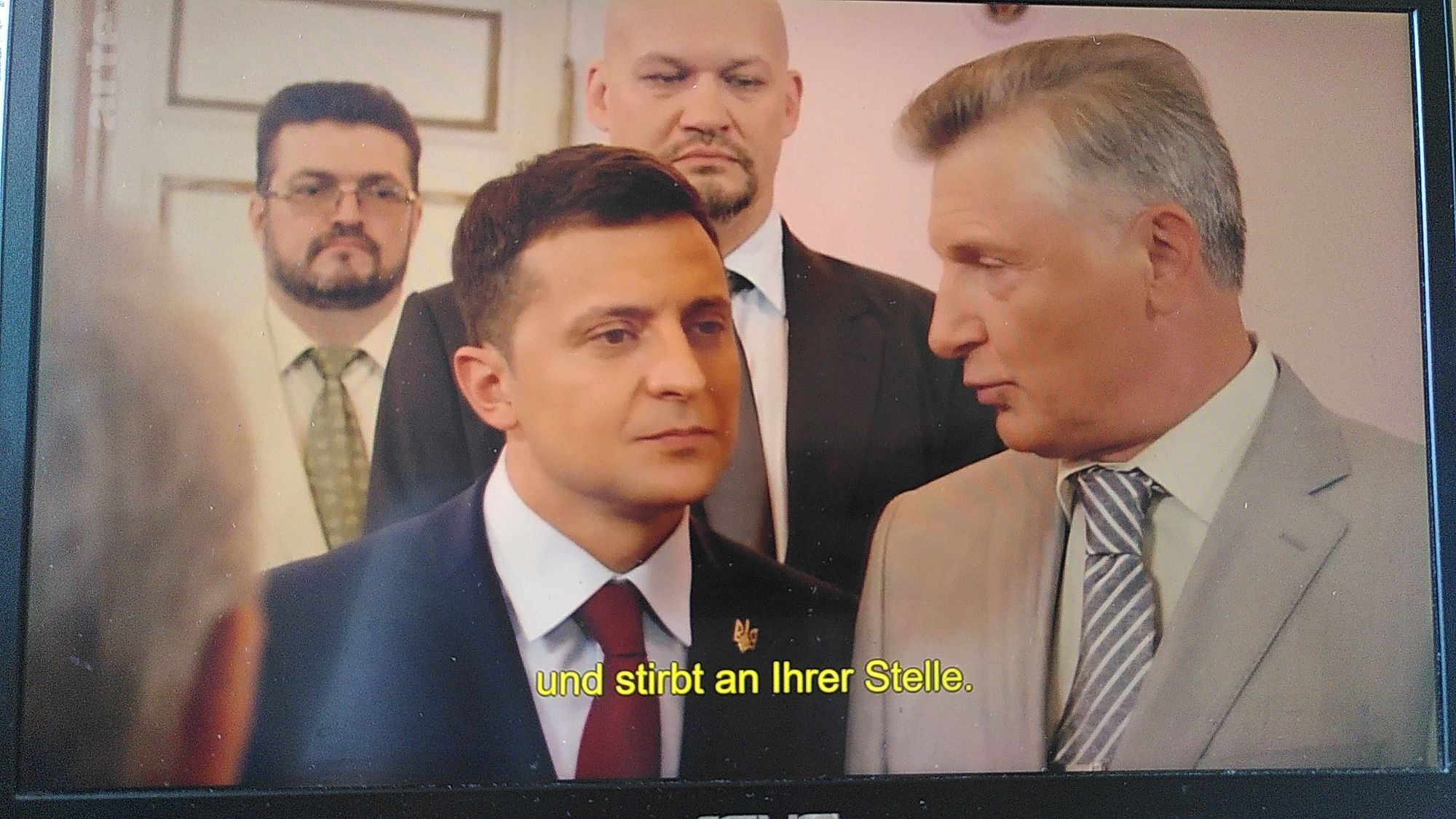

[ think of Selenskyj as a comedian fighting for his life - having survived the environment of harvesting laughter, he has turned a politician in his celebrity after-life, but he also survived this other life as a serious politician, becoming once again a different Selenskyi, a politician zombie wished to be dead by so many, a permanent survivor not only of an ongoing war, but also a survivor of the horror of a life in which the reward of laughter was eradicated :( ]