Legal, but sick

what feels illegal, but isn’t? pic.twitter.com/1TCsdb0sZJ

— selfcnel (@selfcnel) January 3, 2021

For anyone who had the pleasure to be around The Discours for the last decade, the rhetorics of legality is as little a surprise as the rhetorics of psychology. When on the one hand broad societal issues and very abstract conflicts are increasingly framed in terms of "trauma", "healing" and "triggers", terms of legality on the other hand begin to invade the psychological and private space.

Ever more frequently, the ideas of allowance and censorship mediate political meta-debates ("Was darf man noch sagen?"), and a lengthy and convoluted discussion about the question unfolds what e.g. freedom of speech or what "cancelling" really entails (while some would argue that being cancelled is not a problem of legality but only of diminished privilege, others claim it is a precedent for self-censorship and undermine free discours even well before illegality.) In other words: No one believes you get in jail for saying something (while ironically of course under the right circumstances - say, in the wrong country, say, in the wrong context like lying under oath - it could always happen - and it can happen more easily on social media), but precisely that is the problem. The incongruence of allowance and legality.

In itself, this incongruence is nothing special, just a manifestation of dynamic law, of the productive difference between Sittlichkeit und Gesetz, unwritten rules and speculative future law and so on. Everyone knows about this gap, and they know it by heart.

More interesting is how it spreads to privatized phenomena like feelings. In the "so good it has to be forbidden" realm of rhetorics one can map the emotional surface of the environment in terms of perceived 'lawness' or 'lawlessness': Some things "should be illegal" just because they produce so strong feelings in the utterer. "X sollte verboten sein" is a sentence that is structurally fascist, abusing the modal verb of Sittlichkeit and the semantics of Gesetz in a somewhat ironical play, creating a performative speech act different from the legal judgement: the Sollen and the Verbotensein.

Even more fascinating is the framework of perceived legality outside of political discourse. It turns out to be true - and I say this with regard to my own feeling architecture - that many things feel forbidden in everyday contexts, although it is hard to explain why.

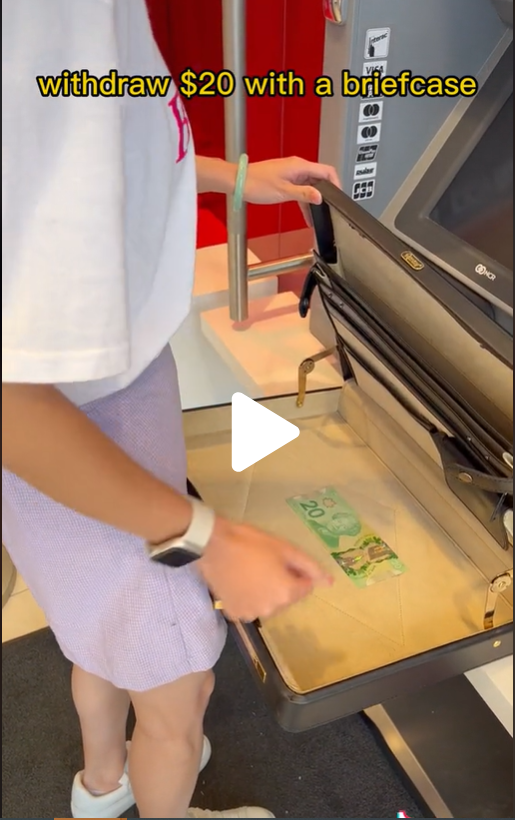

The trend of "things that feel illegal, but aren't" is tackling this structure of feeling, but takes in countless permutations very different turns. Most of the named things - like "taking your own food into a movie theater" or "Secret websites that feel ILLEGAL to know" - might have been called "life hacks" ten years ago, but this term rooted in an environment und user surface that could still be understood in a technological framework: It remembered a time when hacking was a form of life, when using the internet involved chaotic trouble shooting and starting the computer from the BIOS. Now the technological framing of a "life hack" is replaced by a perceived illegality, just as the internet has also become a surface of smooth, but uncertain borders, apps rather than programmes.

find krass wie viele tabs man legal aufhaben darf !!!!!!!!

— une petite ₐᵣₜᵢₛₜₑ (@ohokaycoolcool) August 21, 2022

Ignorantia legis non excusat, but that also means, that one has to infer and speculate about legality and law all the time. In the traffic, while shopping, working, posting on social media. Whether things are forbidden or not is in many ways a feeling, but feelings are themselves - rhetorically, yes, but this means materially, too - also forbidden or allowed. In certain environments this paradox is intensified as the user surface of legal subjects produces an almost fog-like uncertainty.

I am interested in this speculegality architecture, e.g. in the self-checkouts at the supermarket. CCTV surveillance is a given, Stichproben are a calculated risk, the last question before payment (whether you really have scanned all of the goods) presents itself as a total surface-question (like a terms and conditions box) that makes you uncomfortable, because you will never reconsider your basket, but also know that you have to lie over your own certainty and control, deny your speculative approach to law.

While many people seem to steal or "forget" to scan things at these checkouts (as one can see on memes and twitter-jokes), there is also a lot of fascist hate in the very strategic news coverage of people who have been caught by the surveillance of the supermarkets and who have been brutally punished. If you tend to be or become paranoid in this ambience, you might rather go to the conventional cash register. You will be at much smaller risk of becoming a criminal, but the cashiers of course are not. (They never were.)

Online social media is of a similar ambiguos architecture. Past are the times of the outlaw internet. As identification and surveillance have pervaded the web, they do so in such opaque ways that speculegality has become the only feasible way of navigation. The question "was darf man noch sagen" has to be understood as a reaction to exactly this legal transition of the internet, where you have to agree to every cookie on a website as if you could grasp what it means to be an autonomous legal subject in the 2020s. All the while you can only guess whether your data is only scraped by the NSA or also the NDB, the internet service provider, the messaging app, the OS or just the Alexa of your next door neighbours.

All of this is to say: it comes as no surprise that the critique of legality is now a matter of feeling.

The "legal, but sick" videos from tiktok take this a different way: They show social situations lacking decency or courtesy, sometimes outright offensive, when for instance a man is standing right in front of stitting woman in the tube. They come back to the sheer difference of Sittlichkeit and Gesetz. "Sick" in its ambiguity of good or bad is coupled with the ambiguity of "legal" which can also perceived as good and bad - not in a theoretical way, but dynamically, shifting, as determined by the surface environment of speculegality.

For several years, I have tried to understand how literature and world are connected and how they can be modelled in a compelling way (neither the insistence on the autonomy of art nor the postmodern supposition of a totality of textual materiality nor any sociological framework proved to be compelling. Russian formalism and speculative formalism might have come closest to it). I wrote several essays about how the materiality of society might impact the production and reception of literature in a non-trivial way, with mixed results, and pondered in private about "neoformalist" ideas, numerical and statistical approaches, models that involved probability theory or game theory. I still wonder whether one could adjust a semiotic model to exactly the way literature corresponds to the world by including "demeanour" or some factor that accounts for the partly-autonomous art work. Or if one (or two) could find a way to model a logistics that explain materiality in general, such that the difference of world and literature is easier to bridge.

What I chose in my thesis instead was the very crude idea of "poetic license" (which is of course connected to formalism, but propagated by researches I do not really share a lot of similarities with): "Literature" or "poetics" is a subset of language that feels illegal, but isn't. Or, to put it the other way: a language that is legal, but sick. One can speak in metrical rhythms, one can misuse semantics or omit finite verbs, one can write with a Zeilenbruch, but it feels illegal enough to not use it outside of literature.

This solution "felt" in itself "illegal". As an explanation it seemed too easy and did not account for all the things I would consider myself literature. And it did not say anything about the economic materiality of the world. But it is only now that I can see how well it fits into the speculegality architecture of the 2020s. "Free speech" is a feeling. "Cancelling" is a feeling. And "poetics" is a feeling as well, albeit totally different. And all these feelings are feelings in regard to legality or allowance.

At first sight this whole meme trend seems paranoid and would explain why whole generations feel and act as if they are paralyzed, and why the internet feeds into that feeling. But the awareness of those feelings can also be quite the opposite, and open a space of action, even political.

Walking out of a store without buying anything might give rise to a revolutionary feeling. But if everyone did so, it would be a revolution. And we created, at least in the fog of self-checkouts and website cookies and for a short period of time, the illusion as if we could do more than we thought we could.

Of course, the revolution will feel illegal, but won't be.

@theboringkompany Things you can do, but never will #foryou #legalbutsick #unusual #funnyvideos #hilarious #theboringkompany

♬ original sound - The Boring Kompany