Fury Road

In a bit less than a week, I will defend my PhD thesis on literature and car crashes. So, tonight might not be the worst time to write about something I have somewhat ostentatiously not written about within those more-or-less defensible pages.

At the basis of my thesis, there was my irritation about the general acceptance of car crashes; about the way societies seem to regard car crashes as simply a part of a 'nature' untouched and untouchable by human design, and thus as not something anyone could ever really do something about it. This seemed striking to me – and seems striking still – as car crashes are extremely violent, immediately so: unlike the mass death of, say, cancer, car crashes are a fairly uncomplicated feast of gore in the open (I'm not saying dying of cancer is not a violent thing, I'm just saying that it tends to happen in enclosed spaces, the public excluded). It is res publica, violence literally in the middle of the road. And societes derive so much fairly chauvinistic pride, it seems to me, in having banished that sort of extreme public violence; indeed, the display of violence in the public realm seems widely considered a sign of (1) a time past, say, witch burnings in 16th-century Europe; and/or (2) a place remote, say, public executions in countries deemed 'less civilized' than the one I'm writing this from; and/or a social problem that needs to be adressed, if need be with a huge amount of resources, say, gang wars, cartel violence, or massive social upheaval bordering on civil war.

Almost as a rule – if, admittedly, Stammtisch in character – 'developed' societies consider themselves developed not at least on the grounds of their not having extreme violence in the public field, at least not on a regular basis. And if one accepts this haphazard rule, one must admit that car crashes seem to be the exception.

My thesis was concerned with an investigation into possibe reasons for this – and, among other things, with providing a survey of past investigations into the phenomenon (there is not much, but what there is, is for the most part very good). In consequence, it was also an investigation into how automobility managed to make itself at home on this planet, and turned itself into an inevitability – a part of nature, with its adverse effects, such as car crashes, taking the shape of a natural law.

What I did not focus on were other adverse effects of automobility, especially its catastrophic ecological impact; while obviously very important, this aspect rather fell out of my scope because I am ready to concede that although the climate footprint of the car is so bad that it can absolutely be called violence

– violence inflicted not only on 'nature' (whatever that would be), but, by thus being involved and fuelling (pun inteded) the global petroleum circuits and their concomitant acts of warfare, inflicted on the whole biosphere, on plants and oceans as well as on human populations –

I am ready to concede, anyway, that although the car inflicts severe violence on the grounds of its ecological impact, and although this violence happens 'in public', it happens in the most general of publics, namely on a planetary scale, and is thus not in the same way visible as the car crash. Ecological and mechanical impact engender two very different optic regimes, it seems to me, and only the latter – with the person getting a leg ripped off right in front of you, with the wreck visible by the road and lit up by the ambulance lights as you pass by, slowly, in your car, – is still of that old violence that interests me, because it is the 'banned' kind of violence.

So the ecological violence of the car is not part of my research focus, and I have no qualms with myself about this: it was not an aspect that interested me for this specific project. Moreover, it is the aspect that has attracted the greatest amount of car-critic research, so it is not like this is a field that was positively waiting for my valuable contributions.

And it is on these ecological grounds that the car, finally, turns into a contested commodity, that the smug self-assurance of automobility is questioned.

But as the car is contested, its aspect of ecological violence and its aspect of car-crash-violence will intersect in a new way – and it is this intersection, I feel, that is under-discussed in my thesis, under-discussed because from the vantage point of just a little research into past and contemporary automobility, it is so clearly visible that not talking about it is an ostentatious silence.

This intersection can be stated very plainly:

As the car is more and more contested as a commodity, it will be more and more employed as a weapon.

And what I mean by this is that what the 2010s saw as a kind of dress rehearsal, in the Western world primarily associated with Islamist terrorism, will become a lot more widespread in the near future: cars will be used to kill or injure people, especially groups of people, and especially specifically targeted groups of people.

This is also the site where the rule I stated above, and the exception that is the car crash, meets what is maybe the other great exception: mass shootings in the US, which feature extreme violence in the public sphere, and know only half-hearted attempts at pretending that it is not accepted on a systematic level.

If I say 'targeted groups', I mean that the car will be used to maim and kill members of the 'opposition' – those, for example, who oppose the car. In other words still, as ecological tensions rise, and the car will be ever more contested as a sensible way of getting around, more and more ecological objectors will be killed by car. Unlike in most recent precedents – Islamists driving their trucks into celebrating people, Aum Shinrikyo sympathisants plowing into pedestrians – the car will thus not simply be the instrument, but, as it retains its Doppelcharakter as commodity (as which it is contested), the very vehicle (pun fucking intended, you better believe me) of the conflict. And thus, these attacks will, unlike the precedents quoted, receive a lot, and I mean a lot of sympathy of the general public, as this general public will for large, if not major, parts still be helplessly dependent on the car and mistake this abusive relationship for love.

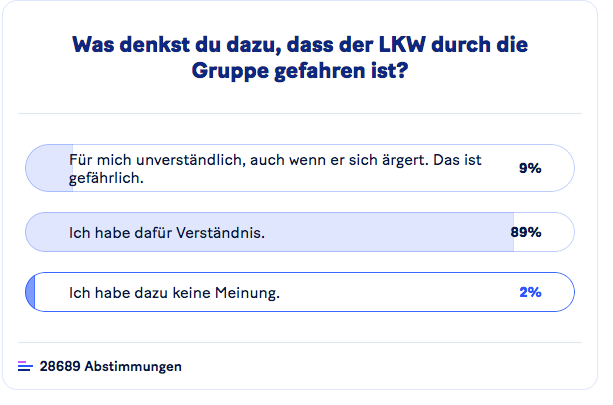

A little survey helpfully done by 20min (you never know where you'll get your help from) will give you an idea of what I mean. The "Gruppe" in question is a group of climate protestors who blocked a road:

(Nothing I write in this text will equal, in density and power, that terrifying question hanging in an online media survey box, like a sentence out of a nightmare, or worse.)

In the vehicular violence visited on climate change activists, two aspects meet in a very dangerous way: the classic bourgeois reaction to any worthwile activist action that goes "I agree with their point, I just don't like how they advocate it", which is obviously meant to say that they like their activism where it doesn't hurt, that is, where it doesn't activate anything but might be nice to look at and feel good while doing so. This At-Least-Femen-Featured-Tits-approach to activism is obviously exacerbated if the commodity or technique protested is one shared by a huge part of society (to reactionary eyes, protesting fracking or private jets at least has the decency to be against something you will never be able to indulge in). People who sabotage a private jet will still garner a shred of sympathy from those who think that everything is a little bit ok as long as it hurts the wealthy, while people who tape themselves to a busy road 'hurt the working man'. Indeed, as the world is infrastructured in ways that make large swaths of it absolutely dependent on the car, any attack on the car will produce any amount of adverse stories: a reddit recent reddit post presented the story of a man on parole who must by all means be on time on his job lest he goes back to prison, but alas, he can't: there are climate protesters blocking the road. The bottom line was obvious: climate protesters who block traffic only pretend to be part of an emancipatory, let's say, of a caring project, but are in fact callous and self-centered, leaving this man hanging. And the dramatic side of this of course all but obliterates the possibility to question why exactly any society should make the freedom of a person depending on his access to one specific commodity, or why one specific commodity made itself so important that a state would find it normal to think that people either have access to it and can employ it in any necessary way at any given time – or must go back to prison.

But this reactionary, anti-activist logistics, produced by a tradition of anti-activism and the specific addiction to the car virtually all societies and thus virtually all social subjects share, is only half of the problem. It is the ideology that hardens the edges of the opinions, and that tips public sympathy for the foreseeable future to the side of the vehicular attacker. Why would you impede on the poor man's need to go to work, the voices will say, why would you. This is what you get.

(There is, of course, something of the office death cult involved in these weird attempts to defend the obligation to go to work on time – very much different from the right to work.)

The other half of the problem is that if I say that the car as contested commodity will be employed, how easily it is transformed from the first into the latter and back. The simplicity with which it transforms or can be transformed is one of the reasons why the car is not exactly 'a commodity just like any other'; is one of the reasons why replying to a critique of automobility that 'well but a lot of things we have are bad for the environment', 'but cigarettes also kill people', etc. are not only intellectually lazy, but a strategy of noyer le poisson, as they say in French: of burying the specific in a heap of the similar.

The other half of the toxic mix, then, lies in the fact that those who will remain steadfastly on the side of the car will remain with the side of the weapon. In other words, the contested commodity can, in doubt, be employed in and of itself as a means to defend its right to exist.

If this sounds too abstract still, all I mean to say is that car drivers will plow into climate activists long before the meat eaters will hunt ecologists down and eat them. (This is not a defense of meat-eating.)

The situation is that as, for example, Black Lives Matter activists consciously choose to protest as pedestrians, and to protest, among other things, the scientifically well-arguable link between white supremacy and 'automobile supremacy', their alt-right opponents have no such qualms and thus remain not only on the side of the commodity, but also of the weapon, helpfully allocated to them by a system of automobility, ready to be driven right into the vehicularly unarmed other side.

Automobility, then, will revisit a state it had been in once already: at the beginning of the 20th century, before it managed to lock itself in place. Now, it is not an understatement to say that the roads of the early 1900s were a site of combat: of an emerging mobility commodity, the car, against more or less all of the established ones, and against an apparatus of established and codified social life. The car had to turn the road – before, a realm shared between all sorts of mobility: carriages, horses, pedestrians, bicycles, streetcars – into a flat asphalt platform, streamlined for only one type of mobility, with a few asylums (crosswalks and the like) for the other mobilities. It had to turn nature into road. And it was fought on all those fronts, in combat that included, among other things, wire stretched across the road to decapitate roadster drivers (this is not an invention on my part... but you'll need to read the thesis if you want to get more of the picture). Before automobile lock-in, people were very well aware that this was a physical attempt of conquest, to be met with equallly physical force.

The car physically bullied its way into the commodity-form, and it will defend it, and it will turn its way out of it into a fury road.

And don't be mistaken: the car-driving side is arming up. In the past thirty years, SUV sales have been on a continuous increase in what the respective research calls 'developed countries'. In 2021, they accounted for almost 45% of all passenger vehicle sales globally, compared with just over 26% in 2019. It just so happens that SUVs are by far the most dangerous cars to pedestrians, not only due to their relative weight compared to sedans or hatchbacks or other, smaller forms of car, but also due to their shape – wide and high front, with prominent, heavy grille and high wheelbase – which massively favors smashing straight into smaller people and bashing their skull in, or pulling them under the car itself in the case of taller people, then crushing them, rather than – in the case of hatchbacks or sports cars – 'scooping up' pedestrians and letting them land on the hood or the windshield, uncomfortable proceedings for the pedestrian in question, sure, but anatomically preferable to the massive injuries dealt by the SUV.

The side that will plow into climate activists is thus not only ideologically prepared to do what it thinks it must, it is also getting its arms ready; all while looking (and probably feeling) innocent, as they only stock up on a commodity whose adverse effects we have grown blind to long ago.

What I have not talked about in my thesis, then, although it would have been part of the focus, because it is very much concerned with the car crash as something accepted, is the intentional car crash as a political weapon, a phenomenon whose age, today, is still only dawning.