Econ Notes #4: After Work, Review

Review

This book filled an important gap for me: The problem of the unwaged work done "at home" was neglected by standard economic school books, but also never rigorously contested in so called "alternative" or heterodox approaches. This statement does no justice to the history of feminist economics that took off - especially in Germany - in the 60s and 70s, I know. But their methods, innovated from scratch and performed under difficult circumstances, were wildly differing in one point that was often only an implicit one and therefore difficult to isolate: Whether unwaged work was to be regarded as good or bad (and is it bad because of being work or of being unwaged?) - and under which circumstances something "good" might turn "bad" (the authors also differ from Fedrici explicitly in this point). This field remains very chaotic to me and "After work", comfortably based on a newer and popular discoursive toolbox of intersectionality, had the luxury to set exactly this point straight already in the subtitle of the book: The "fight for free time", a fight against the "history of the home". I think such a normative decision is no contradiction to research, but on the contrary the axiomatic starting point for any methodical study.

The Ansonia Building in New York

In the end, this book did not entirely fulfill this promise, because it seemed a bit too convoluted to be methodically strict. (But then again: Is this not exactly, what "the home" is? Convoluted, chaotic and heterotopical, yet hegemonical?) What it achieves though, is setting up a framework with astounding examples, statistics and rigor, within one can analyze social reproduction in economic terms. Economic in so far as the authors, while never arguing for a (fair) wage for unwaged work (this would be too naïve vis-a-vis the imaginationary warfare the "home" is confronted with), look at all the work necessary to reproduce the labour power as a complementary work to employment. Both have to be overcome together. (The confusion of all the terms: domestic labour, unwaged labour, reproductive labour, care work, house(hold) work and so on, did not really resolve for me, but I also think that they staid true to the concept of social reproduction and that it might make more sense to look at all these concepts together than to just fail to isolate one). I am, after reading the book, also conviced that the institutionalised "free-time" is engineered to accompany waged work and that it has to be reconceptualized from scratch (though I still have to get used to the ideas of "post-work" and especially its terminology of "choice" and "freedom"). What is no surprise, but also important and probably the biggest achievement of this book is that it collects and remembers historical alternatives and struggles - the way in which they are artifically "forgotten" would be an important point in itself.

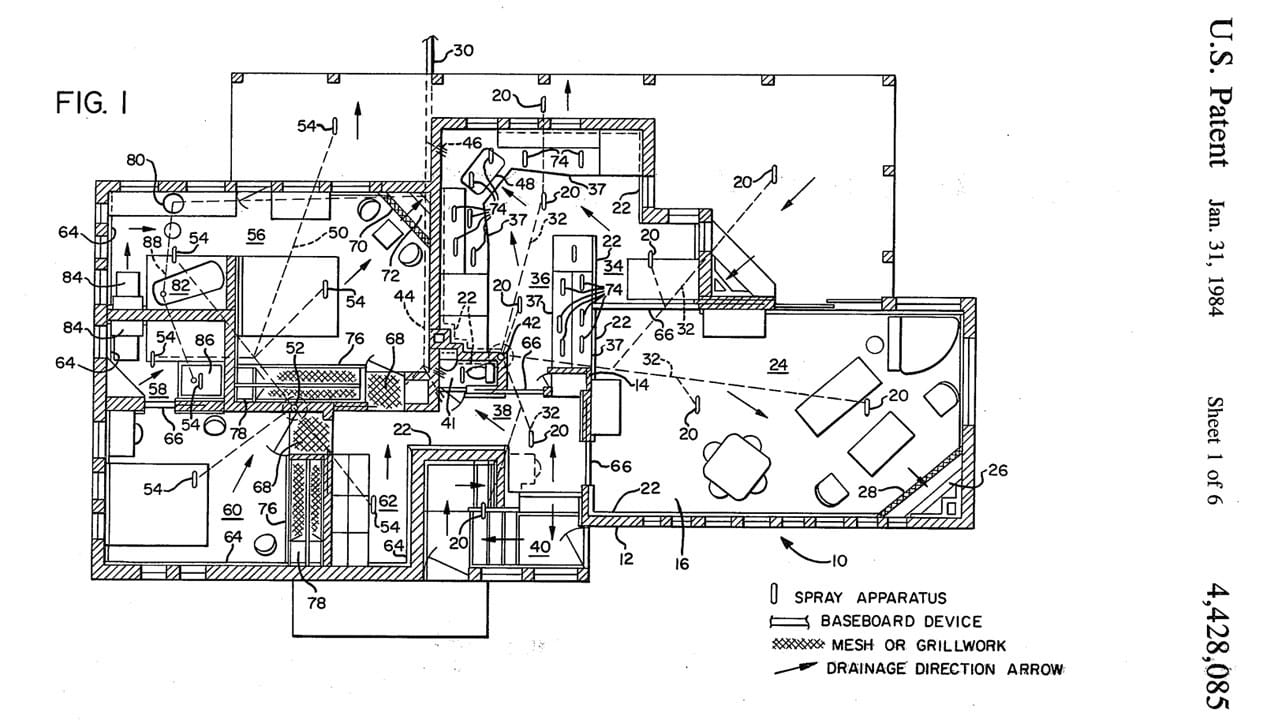

Patent Model of the Self-Cleaning House

The last chapter should have been the programmatic one, a sort of manual to reach a post-work society, and it disappointed me a bit. No big surprise, especially because the rest of the book was so promising and rich. Still, the disappointment tells something more general about the problem of the book which is far more complex than a mere "failing".

Frankfurt Kitchen

The authors seem very cautious. They shy away from oversimplification and always underpin the complexity of paradoxes, trends, technologies. They do indeed point their fingers at disgusting developments (e.g. the social welfare laws) and they show hands-on solutions from Moscows metro stations to Lesbian communes, so it is not a problem of too much abstraction. It is rather that they remain cautious especially when bringing up future ideas of a post-work society: Yes, the relationship of eldercare and autonomy is complicated, yes, work can also be fulfilling when chosen freely, yes, there is a trade-off between privacy and community. And while all these points are important, especially for many oversimplified leftist ideas of exodus communes and family abolition, they tell us not much what we did not know. More than that: A huge part of the book was dedicated to the importance of cultural norms and imaginations (even "guilt"), in order to understand innovation, technology and economy. (Lowenhaupt Tsing or Rosa Luxemburg made this point too, which becomes relevant to see why capitalism needs its "ideology".) The chapter "Standards", about the change in expectations, is one of the most fascinating summaries I have read in a long time. But then, it seems, is the programmatic future outline the authors show not meant to confront these imaginations: Rather than fighting imaginations (or, as I argued, the anti-imaginations like "domestic realism") with imaginations, they fight it with facts and cautionary realistic ideas. I am sure, many people might be pleased with the prospect of having some grounded ideas how to carry on after they have read a political book. But I think, they will still be disappointed, because imaginations need to be more radical than real(istic), more crazy than feasible. The "Public Luxury" principle is very optimistic in this regard: Why fight for good social wellfare? Let's fight for canteens with Buckingham Palace-pictures on the walls!

Narkomfin

Why talk so much about standards, and not be ready to sacrifice them? While they seem to attempt it, they still end up raising expectations for the post-work society, at least regarding children's "right to play". A realistic book about post-work is important, because the idea seems so strange at first. But it becomes less a book against "domestic realism" and "the fight for free-time and the history of the home", because it does not adress fantasies itself. Let's get rid of standards! Let's create new ridiculous expectations that even the "more affluent" cannot compete with. This would be the fun way to achieve this.

While the book does not make statements like these, it is full of examples that did - radical self-cleaning houses and apartments with economies of scale. Thanks to this, the book, at least in parts, still fulfills its promises, not always where you would expect it to do.

The Kitchen Debate

Content:

I - INTRODUCTION

II - TECHNOLOGIES

III - STANDARDS

IV - FAMILIES

V - SPACES

VI - AFTER WORK

VI - AFTER WORK

Freedom and Necessity (this subchapters sets the stage for a post-work imaginary. The authors start by defining the presupposed conditions of abundance and absence of domination, and in this they also let 'work', freshly redefined, return to their terminology)

"Time has been at the heart of this book -- as it must also be at the heart of any post-work, postcapitalist world", the authors write, somewhat surprisingly in a book with a whole chapter dedicated to Spaces but none to time. 153

The authors mean, of course, an emphatic "free time", which is uncommon under Capitalism, a time to choose what to do with it (I remember Fortunatus here - who is not only gifted a "briefcase" with unlimited money as many interpreters summarize the "Geldsäckel". The "virgin of fortunity" endows him with an exlusive "choosing time", in which he is, for a short time-span, as free as he will never be again). But on the other hand, to have this time requires that no one is fighting for bare survival:

"Real freedom therefore requires, as a first condition, what Aaron Benanav calls abundance: 'A social relationship, based on the principle that the means of one's existence will never be at stake in any of one's relationships.' It is only with the assurance of such a situation that everyone will be able 'to ask "What am I going to do with the time I am alive?" rather than "How am I going to keep living?"" 153f.

Abundance is the first condition, the second is absence of domination:

"absence of domination (that is, of arbitrary interference from another) -- a point made in recent years by socialist and labour republicans.4 Unlike more liberal ideas of interference, republicanism notes that domination can occur even if the dominant choose to never exercise their power; the very possibility of arbitrary interference is sufficient." 154

Only under these conditions, then, will freedom redefine work and leisure - as the authors finally attest:

"Such freedom complicates any clear-cut distinction between everyday ideas of work and leisure given that these projects can and will require immense efforts. As Marx wrote, 'Really free working, e.g. composing, is at the same time precisely the most damned seriousness, the most intense exertion.' But this activity, though potentially demanding, frustrating, and onerous, will be free insofar as we commit ourselves to it for its own sake rather than being coerced into performing it by material need." 154f

But what can be said about a utopian social reproduction? There is a realm of necessity of this work, but it is historically (and culturally) variable - they use the example of food and how its necessities differ in different cultures. And there is also a realm of freedom, which is sometimes hard to seperate from necessity. In fact - and this is interesting - such freedom can only be 'felt' internally and in retrospect. I quote the whole paragraph, even if I think it is very questionable:

"Yet the work of social reproduction occupies an interesting position in regard to the distinction between a realm of necessity and a realm of freedom. It is determined by needs (therefore of the realm of necessity) but can simultaneously be determined by free choice (the realm of freedom). We can find an example of this from own lives in childcare. Even deep in the weeds of nappy changing and sleepless nights -- when the oldest is sick, the youngest won't settle, and the middle child is having a tantrum -- we can recognise that we are engaged in a project that has largely been freely chosen. We are thus undertaking individually unfulfilling tasks as part of a larger satisfying end. The same goes for the act of cooking, in which many people take pleasure and pride. Labouring over a hot stove may not be intrinsically fulfilling, but it can take on the quality of being a freely chosen activity in the arc of a larger self-directed goal. What these examples show is that even necessary labour can be free given the right conditions." 156

After this statement they reformulate their post-work vision (in very persuasive words, I think):

"The goal is to reduce necessary labour (or 'work') as much as possible while expanding freedom (or 'free activity') as much as possible. This might occur through the technological reduction of work, the sharing of burdens, or the management of expectations, but also through transforming our relationship to the activities we undertake." 156

In other words, abundance is a form of 'post-scarcity', but not in the material sense, but in the temporal sense: "a world in which access to life's essentials is no longer contingent on selling one's time to another." 156

Principles (this subchapter states three general ideas of their vision, with the according parts: Communal Care, Public Luxury and Temporal Sovereignity)"

"Our goal here will not be to set out a blueprint for the future -- as if such a task wasn't impossible -- but rather to elaborate principles and suggest some concrete possibilities for how to move forward." 157

A) Communal Care

The authors summarize the arguments in favour of communal care and against the "nuclear family":

- Evading patriarchal structures

- Breaking the concentration of wealth

- Domestic abuse (gendered, but also against elders)

- Hate and frustration within care relations (A Japanese study from the mid-1990s, for example, found that half of the caretakers surveyed had abused their relatives, while a third admitted feeling hatred towards those they cared for.)

- In general, LGBTIQ-unfriendly

- Most importantly, the family is inefficient ("It is hard to argue that the family is an adequate vehicle for care when members of nearly 20 per cent of nuclear families are estranged from each other." 159, Endnote: "This includes 10 per cent of people who are estranged from a parent or child and an additional 8 per cent who are estranged from a sibling. A further 9 per cent are estranged from extended family members. Pillemer, Fault Lines, Ch. 1.")

Unsurprising summary of this first principle: "Or what if we could imagine the provision of adequate care in terms of comradeship, mutual aid, and other forms of collective provision rather than just those of biological kinship?"

B) Public Luxury

"In our cities this [Public Luxury] would involve infrastructural extravagance: some space of our own in which personal needs could be met, massively augmented by a revived commons. [...] While public provision, particularly in the US and UK, is often seen as a last resort -- low-quality back-ups for the poorest in society -- public luxury demands more, and might easily draw inspiration from places like Helsinki's lavish Oodi Library, Moscow's famous metro stations, or the stylish public housing of Vienna. The demand for such public luxury could be the rallying cry of a revived twenty-first-century social democracy." 161f

Such infrastructure could provide not only a place in which the occupation of free time can be chosen more freely, but also a removal of some domestic work from the home. 162 Apart from infrastructural projects they also mention smaller ideas of luxury, like the communal ownership of tools. All of this need not be a competition to self-owned tools or structures.

C) Temporal Sovereingty

Admittedly a bit obscure to me, this principle should be understood under the conditions of "postcapitalism". Under capitalism, time is subject to trade-offs based on "value". Decisions come always with a caveat, one day off work to care for children is not a free decision when payment is substantially lower.

"capitalism's imperative to accumulate for accumulation's sake no longer operates as the regulative meta-norm to which all other norms must conform, and these norms can no longer be warped by its gravitational pull. Newfound free time -- new in both a quantitative and a qualitative sense -- opens up the problem of freedom. Keynes famously set the question out thusly: 'For the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem -- how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well.'39 Yet Keynes' 'problem' is only intelligible outside of a society organised by capitalist ideas of value -- a society where the possibilities imposed by value's systemic domination are no longer operative and where the question of evaluating trade-offs opens up." 165

But the temporal sovereingty would not be concerned with individual decisions alone: "We are social beings, and temporal sovereignty therefore means authoring our own norms and obligations to the collectives in which we live [...] This also involves building mechanisms that allow for individuals to determine their own separate paths. After all, a post-work, post-scarcity, postcapitalist world is not one devoid of contestation and conflict. There will always be different values to choose from." 165f

Social Reproduction under Capitalism (this subchapter outlines some first steps and ideas to reach a postwork society of social reproduction)

"Crucially, this work would be distributed equitably -- from each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs. [...] As an immediate (if small) step towards this, we might consider something like Nancy Fraser's 'universal caregiver model', which aims to support everyone as individuals with social reproduction responsibilities." 167

"While everyone with the capacity to do so would contribute to the necessary reproductive labour of their communities, people would no longer find themselves automatically funnelled into certain roles. [...] All people would have an appropriate share of work to perform, rather than simply a job to perform." 168

But this is only a new distribution of labour to dismantle the normative roles and imaginations of reproduction. While it does not reduce the total amount of labour, it is an important step for example to create alternatives to the nuclear family:

"This wouldn't have to mean the withdrawal of those benefits that currently accrue to biological families, but rather the extension of those benefits to different kinds of relation; they might initially go beyond the merely marital or parental to more fully encompass bonds forged by friendship, community, or extended kinship." 169 - This has to be adjusted by state policies, as Michèle Barrett and Mary MacIntosh have argued. Friends for example could be "included as a category".

Cuba's Families Code:

"Cuba's recently passed Families Code is one possible model to emulate here. It offers an encouragingly expansive definition of 'family': 'a union of people linked by an affective, psychological and sentimental bond, who commit themselves to sharing life such that they support each other'; greater rights afforded to children (e.g., 'parental authority' is replaced by 'parental responsibility'); and demands for equality in domestic labour. These kinds of reforms may have the potential to enable caregiving practices to flourish beyond the specific confines of the heteropatriarchal family and could therefore represent an initial move towards the more equitable and effective sharing of reproductive labour." 169

Regarding childcare, they name the examples of Denmark and Germany with their subsidized childcare facilities. Denmark even provides it for "the poorest" for free. And another example of infrastructure:

"We might first imagine following the Welsh example by turning play into a right. through legislation. This means that Welsh cities must now ensure there are nearby spaces for children to play, local councils should offer activities to support children's free time, and housing developers must assess how new developments will impact children's opportunities for recreation. Greater autonomy would also grant children enhanced capacity to leave abusive situations and place limits on parents' power over them." 171

Regarding eldercare: "When it comes to elder care, proposals around communal provision require some delicacy. [...] While we must recognise that the decades-long trend towards at-home care is absolutely a measure of government cost-cutting, it nevertheless tallies with the genuine preferences of many care recipients." 172

Co-housing as an alternative: "London Older Lesbian Co-housing, for example, started from the perspective that residential care homes or independent living schemes may not be ideally suited to those who have not lived much of their lives in heterosexual nuclear families, and therefore that older people (should they experience discomfort being out in these settings) could feel as if they were being pushed back into the closet as they aged." 173

But also the possibility of technology: "Furthermore, we could utilise digital platforms -- shorn of their profit-making imperatives -- to help coordinate the needs of care recipients with the provision of care suppliers." 173 And, one very interesting idea of a 'neutral zone': "To supplement such spaces, infrastructure for communitybased long-term care could also be built -- spaces that are distinct from both the home and the hospital but which can house the proper resources demanded by carers and the cared for." 173 Including training sessions to use the equipment. This would demedicalise the home and give the caregivers a space to relax:

"All of this could be run in turn by cooperative care groups, perhaps following something like the influential nurse-led Buurtzorg model from the Netherlands, in which self-managed teams of nurses based in specific neighbourhoods cooperate with individuals and wider community networks (including relatives, friends, and neighbours) to help people age well in their communities." 173

Regarding food: "As a first stage, we might imagine universal free school meals and breakfast clubs being provided for primary and secondary schools. Finland, for example, has had a free school meal programme in place since the 1940s, with all pupils provided with a decent meal, from pre-kindergarten right through to the end of secondary school.69 The UN has also recently set out universal school meals as an important part of the right to food." 174

Even though they are in favor of a return of canteens, the authors admit that individual kitchens are here to stay. (Which is surprising, considering that indeed "many contemporary experiments in collective living continue to revolve around a shared kitchen" 175).

Elite's communism (not their term, but I was thinking about the famous saying "Communism for the rich"): "As Rebecca May Johnson notes, 'It is telling that while there are no public canteens in the city (what council could now afford to hang on to such a quantity of land after cuts?), the houses of parliament have ten canteens.' Here [in the UK], members of Parliament can select among subsidised offerings ranging from roast sirloin to panseared salmon to chargrilled chermoula spiced squash -- all at about the same price as a sandwich and coffee from Pret. In the face of images of decrepit public services, we must insist that 'the idea that mass catering must be devoid of pleasure is false'."

And they also bring up a stunning historic example: "While mostly thought of as a period of ration books and household scarcity, the war was also a period when many of society's worst off ate their best. In response to the problems of feeding the population during wartime, the British government set up 'communal feeding centres' -- a name which was eventually vetoed by Winston Churchill as sounding too communist and replaced with the more nationalistic 'British Restaurants'. Some of these canteens had table service, others were organised more like a cafeteria, and many had services by which people could order food to take home. In rural areas, there were even mobile services that would travel around to offer food. At their peak, these communal feeding centres were producing around 4 million meals every week. Their walls were decorated with works of art taken from Buckingham Palace and the national galleries -- perhaps as good an example of private versus public luxury as one is likely to find." 176

Regarding other labour: "More likely, housework will continue to be performed by humans for the foreseeable future. As an approach to better managing this, we might imagine (as thinkers such as Alexandra Kollontai and Angela Davis have) teams of professionalised, well-remunerated cleaners efficiently taking up the necessary labour. [...] To help with the costs, states such as Belgium, France, and Sweden have also subsidised payments for housework. As things stand, these subsidies could perhaps be focused on those in need of long-term care (be they disabled and/or elderly) -- as evidence suggests that these are the people most in need of such outsourcing and most amenable to taking it up when it is affordable. We could also imagine greater support for launderettes, organising the laundering needs of a community in a way that is far more temporally efficient and ecologically sustainable than current domestic methods."

Regarding spaces: "And a common refrain from experiments with failed communes is that privacy was neglected. These desires can't simply be dismissed as ideological mystifications, false consciousness, or knee-jerk reactions; rather, they speak to genuine feelings, preferences, and needs." 178 (whatever 'genuine needs' are...)Therefore "private sufficiency" is as important as "public luxury".

"Dolores Hayden pursues this line of thinking in her classic article 'What Would a Non-Sexist City Be Like?' In imagining a metropolitan co-operative made up of forty households, she demands the following collective spaces and activities:

'(1) a day-care center with landscaped outdoor space, providing day care for forty children and after-school activities for sixty-four children; (2) a laundromat providing laundry service; (3) a kitchen providing lunches for the day-care center, take-out evening meals, and 'meals-on-wheels' for elderly people in the neighborhood; (4) a grocery depot, connected to a local food cooperative; (5) a garage with two vans providing dial-a-ride service and meals-on-wheels; (6) a garden (or allotments) where some food can be grown; (7) a home help office providing helpers for the elderly, the sick, and employed parents whose children are sick. The use of all of these collective services should be voluntary; they would exist in addition to private dwelling units and private gardens.'" 179

Until now and with the exception of the digital platforms for eldercare, the authrors did not really relate their ideas to contemporary technology. But they add some examples:

- "A phone and computer repair shop, for example, with a mobile team of technology trouble-shooters might prove to be a useful resource for older residents (and anyone whose Wi-Fi router has ever inexplicably stopped working). "

- "For parents and caregivers there could be an ecologically friendly reusable nappy laundry service, a baby clothing rental service, regular breastfeeding support groups (with peer counsellors available for home visits on request), pre- and post-natal mental health groups, specialist baby and child loss counselling, a homework help centre, and so on.)"

- "There could be free, expansive, networked spaces for collaboration, as well as high-spec, communally accessible makerspaces, including everything from screen printing facilities, sewing machines, and kilns to top-of-the-line 3D printers; regular classes could be offered to those who wish to learn how to use these technologies, and a team of technicians could be made available to support people in realising their projects." 180

- Participation! "Communities could be turned from passive recipients of technologies into networks of active creators."

On the topic of participation in technology there are some stunning examples of anabaptists:

"As Hayden writes of one Christian sect with communalist ambitions,

'The Shakers have to their credit an improved washing machine; the common clothespin; a double rolling pin for faster pastry making; a conical stove to heat flatirons; the flat broom; removable window sash, for easy washing; a window-sash balance; a round oven for more even cooking; a rotating oven shelf for removing items more easily; a butter worker; a cheese press; a pea sheller; an apple peeler; and an apple parer which quartered and cored the fruit.'

Members of the perfectionist religious society the Oneida Community, meanwhile, 'produced a lazy-susan dining-table center, an improved mop wringer, an improved washing machine, and an institutional-scale potato peeler'." 182

And the amazing example of the patented self-cleaning house by Frances Gabe, which is worth quoting at length:

"In each room, Ms. Gabe, tucked safely under an umbrella, could press a button that activated a sprinkler in the ceiling. The first spray sent a mist of sudsy water over walls and floor. A second spray rinsed everything. Jets of warm air blew it all dry. The full cycle took less than an hour. Runoff escaped through drains in Ms. Gabe's almost imperceptibly sloping floors. It was channeled outside and straight through her doghouse, where the dog was washed in the bargain ... The house, whose patent consisted of 68 individual inventions, also included a cupboard in which dirty dishes, set on mesh shelves, were washed and dried in situ. To deal with laundry -- in many ways her masterstroke -- Ms. Gabe designed a tightly sealed cabinet. Soiled clothing was placed inside on hangers, washed and dried there with jets of water and air, and then, still on hangers, pulled neatly by a chain into the clothes closet. Her sink, toilet and bathtub were also self-cleaning. Naturally, no conventional home, with its drapes, upholstery and wood furniture, could withstand Ms. Gabe's restorative deluge. But she had anticipated that. Her floors were coated with multiple layers of marine varnish. Furniture was encased in clear acrylic resin. Bedclothes were kept dry by means of an awning pulled over the bed before the cascade began. Upholstery was made from a waterproof fabric of Ms. Gabe's invention, which looked, The Boston Globe said in 1985, 'like heavily textured Naugahyde'. Pictures were coated in plastic and knickknacks displayed behind glass. Papers could be sealed in watertight plastic boxes; books wore waterproof jackets invented by Ms. Gabe. Electrical outlets were, mercifully, covered." (this is quoted from Fox, 'Frances Gabe, Creator of the Only Self-Cleaning Home, Dies at 101'.)

Sketch for the patent

The authors stress that we do not know how a technology based on sharing and participation would develop and in which directions it would lead us (remember that many domestic technologies were supply-driven).

"The examples we have considered here also indicate that socialist technology does not necessarily mean bigger, more centralised technology." 185

Conclusion

In this conclusion, they immediatly add some caveats for a post-work ambition:

First, post-work is not all, rather it is dependant on certain labour processes (care for instance is not to be reduced but to be expanded):

"While all of the above provides a sketch of how social reproduction might be organised within a transitional or post-work society, it is nonetheless the case that post-work is only one desirable goal among many." 185

"More free time is just one value in a postcapitalist world -- an important one, to be sure, since free time provides the basis of self-determination, but not one without trade-offs. It might be clear that the mining of natural resources should take a minimum of human activity, for instance, but the same does not hold for the labour involved in raising a child." 185f.

Second, the authors stress that while the post-work ambition is aiming for efficiency, this factor should not sacrifize other aspects ("Urban farming, for example, is a useful way to secure access to food for expanding city populations -- and evidence suggests that it can have higher yields and be more sustainable than more industrialised forms of agriculture. Yet it would also entail giving up on the efficiencies that can emerge from more monocultural and industrial forms of food growing." 186f.)

Third, ecological impacts are to be considered.

Fourth, a "post-work society should not be mistaken for a utopian endpoint, then, but instead understood as part of an unending Promethean process of extending the realm of freedom. [...] The goal of minimising necessary labour in order to expand the realm of freedom is a condition for being able to ask these questions in a substantial way. [...] We need the freedom to determine the necessary." 187