Econ Notes #5: A Defence of the Concept of the Landowning Class as a Third Class, Review

F.T.C. Manning (2022): A Defence of the Concept of the Landowning

Class as the Third Class. Towards a Logic of Landownership, in: Historical Materialism 30.3, 79-115.

When this beautifully titled paper was released in Historical Materialism in 2022, it made quiet a fuzz. FTC Manning, a philosopher, activist in the San Francisco Community Landtrust and part of the human geography strand of Marxism (a scholar of David Harvey, if I am not mistaken) "defends" or rather excavates a concept of Marx to adjust the two-classes-model.

When I heard about it (and it stuck in my mind - what a beautifully cautious, confident and cohesive title, so Marxist in its scientificity! I only had listened to the podcast yet), I told one well-Marx-read friend about it. "Did you know, that landowners are also a class in Marx's framework?" - "Yes, that makes sense!", he says without hestitation, "the Parzellenbauer."

The Parzellenbäuer*in is one of the protagonists (or rather cameos) of the 18th Brumaire and their status is very complicated: Their landownership, which is rather the ownership of a Parzelle, alienates them even from the alienation of the proletariat. Structurally, the Parzellenbäuer*in is, in their demands and needs, very similar to the Proletariat, but since all Parzellen are divided from each other, they do not allow for any possibility of class consciousness, topologically, in a way. (This is where the mole of history emerges.)

But F.T.C Manning does not base her defense on the 18th Brumaire, rather she finds quotations in his later writings on the Theorien über den Mehrwert and in the economic manuscripts Engels would later compile to Capital Vol. 3. Here, it seems, landowners are not a class 'extension' or fraction in the two-class-divide between capitalists and proletariats like so many others (finance capitalists, petty bourgeoisie or lumpen proletarian for example). They constitute an autonomous class:

While Marx often uses the term ‘class’ to casually refer to groups like merchant capitalists, he describes landowners as something more: landowners are one of the three classes of modern society. (80)

This is quite surprising, but it is more than a Marxian slip: Especially in the chapter no. 6 of Capital Vol. 3 on the Verwandlung von Surplusprofit in Grundrente, it becomes clear that Marx has developed a whole concept of the landowner.

MARX AND LANDOWNERS

Marx writes of some "Schriftsteller, theils als Wortführer des Grundeigenthums gegen die Angriffe der bürgerlichen Oekonomen, theils in dem Streben das capitalistische Productionssystem in ein System von „Harmonien“ statt von Gegensätzen zu verwandeln" who argue for an identity of ground rent and capital interest.

Jene Schriftsteller vergessen, ganz abgesehn davon daß die Grundrente rein, und ohne den Zusatz jenes Zinses für dem Boden einverleibtes Capital existiren kann und existirt, daß der Grundeigenthümer in dieser Weise nicht nur Zins von fremdem Capital, das ihm nichts kostet, sondern obendrein noch das fremde Capital in den Kauf und gratis erhält. Die Rechtfertigung des Grundeigenthums, wie die aller andren Eigenthumsformen einer bestimmten Productionsweise, ist die, daß die Productionsweise selbst historische (transitorische) Nothwendigkeit besitzt, also auch die Productionsverhältnisse und Eigenthumsformen, die aus ihr entsprangen. Allerdings, wie wir später sehn werden, unterscheidet sich das Grundeigenthum von den übrigen Arten des Eigenthums dadurch, daß es auf einer gewissen Entwicklungshöhe, von dem Standpunkt der capitalistischen Productionsweise selbst aus als überflüssig und nuisance erscheint." (MEGA online II/4.2: Das Kapital, Ökonomisches Manuskript 1863-65, Teil 2, 674f.)

This historical necessity of the landowning class is "peculiar", because it it is constitutive for the capitalist production - this is important - while from the view of the capitalist the landowner seems to be "superfluous", a nuisance. Manning develops or explains (I cannot completely trace it down in Marx, but "completion" is not a way in which Marx interests me anyway), a trinity of classes, in which the function of the landowning class is just, somewhat amusingly, to own land and therefore to create a scarcity:

Each class arises from material conditions that differ absolutely from those

of the other two classes. Proletarians own naught but their labour power; capitalists own the means of production; landowners own land. These classes are all functionally necessary for the reproduction of the capitalist mode of production in its most basic, unadorned form. Capitalist production requires labour from the worker, the dominance of the capitalist in the production process, and it requires that land be owned. (83)

In Marx's own words:

"Das richtige an der Sache nur das: Die kapitalistische Produktionsweise vorausgesetzt, ist der Kapitalist nicht nur ein notwendiger Funktionär, sondern der herrschende Funktionär der Produktion. Dagegen ist der Grundeigentümer in dieser Produktionsweise ganz überflüssig. Alles was für sie nötig ist, ist, daß der Grund und Boden nicht common property ist, daß er der Arbeiterklasse als ihr nicht gehörige Produktionsbedingung gegenübersteht [...]" (MEW, Bd. 26.2,. S. 38)

Beyond the historical reason of landownership, exemplified in the famous enclosure of the so called primitive accumulation, there is also a logical reason for the capitalist mode of production: land needs to be withdrawn from common property to keep wage labour in place, but this withdrawal is not caused by capital itself, rather the landowners can even profit from capitalists on the land.

Manning reminds us that this opposition between landowners and capitalists is not a problem at all, rather is the consequence of a class conflict which constitutes the classes themselves (like the class conflict between capitalists and proletarians). And also, it is not a problem for Manning that people can be in two classes at once:

Sometimes, a person or company is at once both ‘landlord’ and ‘capitalist’.

This can also be the case for the capitalist and wage worker – for example, a capitalist who owns a majority share in a series of shoe factories may also be employed as CEO of the shoe company, thereby receiving a wage as a highly paid labourer, in addition to receiving profits as a capitalist.

This is persuasive, while at the same time very debatable. I know there is plenty debate whether a CEO with majority share is in two classes or is in fact always a capitalist and discussions about what would happen to classes if it is not a category of people but rather of functions. The crucial point I think, is the fact, which Manning shows later on, that landowners and capitalists are very often not identical; that even if the notions like "asset-based financialisation" suggest otherwise they indeed work differently.

HOW IT WORKS

Groundrent has two parts: Differential rent which stems from the nature and quality of the soil/land in relation to other land. And absolute rent which comes from the monopoly power of the landowner to withdraw the land altogether.

And if we look at global landownership, we can observe a strong tendency

for landowners to hold unused land even when there is demand for it; vacant apartments plague the world’s metropoles (especially those where rents are high and rising); up to 40% of farmland taken through recent waves of global land-grabs sits fallow, sometimes with its previous tillers and residents looking on in sorrow. (89)

Land can be withheld until the landowner gets a guaranteed surplus. The landlord's "willingness to withdraw land from the market poses a barrier to capitalist production" and innovation because any increase in productivy can be partly captured by increase in rents. This is especially important in less flexible crop cultivation for example - depending on demand elasticity. Also of course in every large city where luxury apartments tend to be empty.

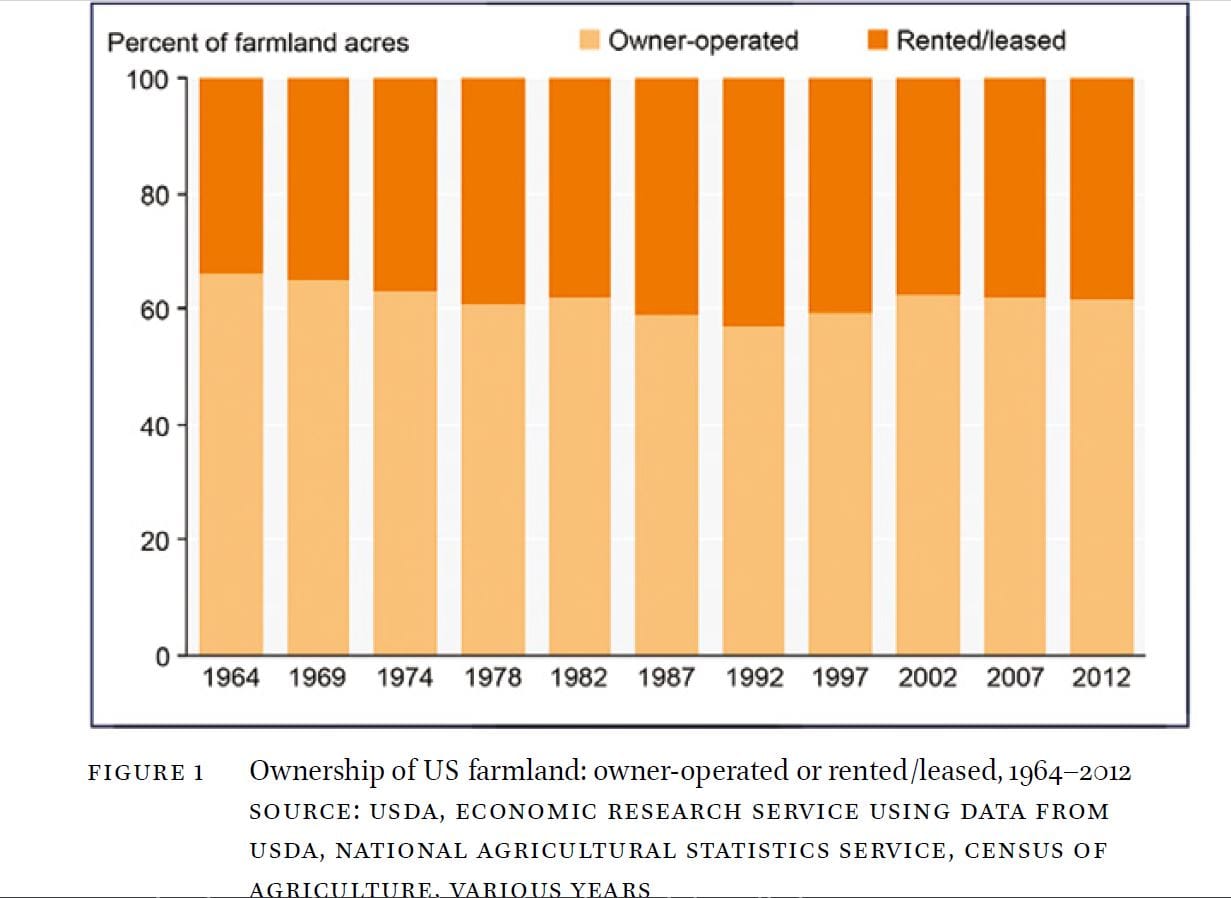

In some broad empirical analyses, Manning shows that "where it is more lucrative to be a landowner (where rents are higher) there are more distinct landowners". In the US, "about 40% of farmable land is rented to capitalist farmers by mostly non-farmers". (100)

And the significance:

Rent as the percentage of operating expenses for farming companies has also increased. This means that landowners have both managed to increase the acreage they control to capture a higher percentage of and profits from agricultural companies over the last several decades – decades in which, according to scholarship on the ‘financialisation of farmland’, agricultural land in the US has been under siege by big finance. (101)

The power of the landowners to set the ground rent can also be seen in the fact that "the majority of agricultural subsidies tend to be appropriated by landowners rather than capitalist farmers" (107). The (other) class struggle is on! And, apart from agriculture, here is a crucial example of the difference between big capital firms and real estate companies in "high-rent sectors", worth quoting in length. As Manning explains in the podcast, this is not because of a classic 'division of labour' between landownership and capital (how would that even work?). On the contrary, these firms would love to own the buildings they are using, building and even naming because land as an asset is very riskfree, but they often do not have the liquidity to do so.

The Salesforce tower is the newest iconic skyscraper in the city and has reshaped the San Francisco skyline. The building is named after the tech services company Salesforce. However, Salesforce does not own the building, but rather holds a 15-year lease, valued at over $560 million, on much of the building. Boston Properties, a commercial real-estate company, owns over 95% of the building and collects rent from Salesforce and others. Similarly, LinkedIn has a 10-year lease on a skyscraper at 222 Second Street from the real-estate company Tishman Speyer, and Twitter rents several floors of an impressive edifice owned by Shorenstein Properties.

Boston Properties, Tishman Speyer, and Shorenstein are all long-standing real estate companies, and provide long-term leases to companies. Boston Properties is a Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) founded in 1970 (a very early REIT). Tishman Speyer began as Tishman Realty & Construction over a century ago in 1898, transforming into a privately-held limited partnership in 1978. Shorenstein is a real-estate investment company, previously called Milton Meyer & Co., dating back to at least before 1941 when Walter Shorenstein joined the company (Shorenstein was also the villain behind the I-Hotel struggle and controversy in San Francisco in 1968)." (105)

The logic of the landowner class, at least in high-rent sectors, is straight forward:

Fundamentally: Landlords raise rents whenever and however they can, and the ultimate limit to what they can charge is what their tenants can pay. Landlords in apartments fight for their right to raise rents at least once a year – and in farmland, too, 57% of farmland acres rented in the US renew their lease annually (even though 75% of acres have been rented to the same tenant for over 3 years, and 34% for over 10 years).

Other stats also show that rising rents always correspond to the ability to pay and not to any other factor: "[A]verage rental costs correlate with average household income – and [...] rents do not correlate significantly with housing

supply or rent control." (108)

WHY DOES THE CONCEPT OF THE THIRD CLASS NEED TO BE DEFENDED?

This is all very interesting, helpful and insightful, but not so shocking since many struggles nowadays (and especially in colonial contexts) develop around land ownership. We know the power of the ground rent is huge, even though we mostly call blaim "capitalists" for setting it.

More shocking as these facts and even more shocking than Marx's mentioning and sketching out of a third class is the fact that this third class either has been ignored or refuted in scholarship. While Kautsky for example still relies on the concept, Lenin deliberately refuses it. Apart from some examples (like Martha Campbell or Roman Rosdolsky), most researchers have been following Lenin's dismissal. Manning adresses several counterarguments brought forward:

(1) landowners are a leftover from pre-capitalist social forms;

(2) landowners are a or of the capitalist class;

(3) landowners-as-class subset fraction with the development of capitalism

(4) the landowning class wither away is replaced, in ‘late’ or ‘financialised’ capitalism, by a class fraction rentier. (90)

Against (1):

The feudal-residuals position falls into the trap of ‘articulationism’ criticised by Michael Neocosmos (1986), in which scholars tend to treat major differences of form within social formations – such as the existence of a landowning class in capitalism – as things that ‘can only be accounted for with reference to the articulation of different (usually pre-capitalist) modes of production with an ideal capitalist mode.’ (91)

Against (2):

Today, the class-fraction argument frequently coincides with the idea that landowners are subsumed by finance capital. For example, Clarke and Ginsburg write that during the twentieth century ‘the landowner as a separate interest has declined and finance capital has increasingly penetrated landownership’. [...] Landowners, therefore, cannot be a subset of the capitalist class, for they do not own the means of production; they own only land. [...] To believe the class-fraction argument, therefore, one must elide ground rent with interest and profits, conflating the reproduction of landownership with the reproduction of capital. (90f.)

Poulantzas is a special case as he agrees with Lenin and admits that "the politico-ideological strength of the landowning class pre-capitalism led to the landowning class forming an ‘autonomous fraction’ throughout the transition period". But after the transition period it is no longer nescessary. Manning at this points hint to the fact that there is still a class opposition going on between ground rent and capital which is not in place with other fractions of capital like merchant capital or loan capital might do.

Against (3):

In a similar vein, some "theorists argue, alternatively, that the landowning class is essential for the beginning period of capitalism, but that the landowning class then essentially ‘withers away’ as capitalism progresses." (94) "Because of the barrier it poses to production, capitalism will not tolerate it in the long term." (95)

This position fails in both historical and theoretical terms. Historically, land owners appear increasingly powerful within the global economy and regularly come into conflict with capitalist-class interests. Theoretically, the fact that landed property presents an obstacle to capitalist development does not mean that landed property stands outside the CMP. (95)

Against (4):

The trendier concept of the "rentier class" in recent years:

Rather than disappear, Harvey suggests that rent and landed property are

transformed. He argues that financialised landownership is the properly capitalist form of landownership, and that all economic agents increasingly tend to treat land as a ‘pure financial asset’. (97)

In so far as the rentier is a monopolist, it is a closer description to the landowner than as a fraction of capitalists: "While a financier collects any type of economic rent (interest, dividends, bond yields) the rentier collects a rent for the use of a monopolised resource. The rentier’s power derives from monopoly power."

But this in turn conflates differences between monopolies and assumes that "rent paid for the use of privately-owned land has the same character as ‘rent’ paid for intellectual property" (98)

This conflation obliterates all that is specific about the form of ground rent – especially the finitude of land (key to its monopolisability) and the fact that land is not produced. (98)

CONCLUSION

This paper is fresh, smart and - I will always repeat it - perfectly named. By grounding itself on Marx it also relaunches a discussion about the weakest of Marx's theories: the class opposition. As it is so naive, so vulgar and so unfit to explain the tendencies, employment relationships and capital behaviour in the 2024, any adjustment to it is welcome. In this case, the arguments for a landowning class are convincing, but one has to appreciate the almost literary character of this class explictily: Its only function is to take away space. Space invaders. I love this, and I also like that it gets rid of the idea that capitalists are the only class with power and inhuman, xenophobic interests, and I think this might help to get a clearer image of the real power and responsability of capitalists in the end.

Astounding how such a Marxist concept might have been forgotten, and especially: why? Of course, it is kind of a stunt to try to compile something out of these late manuscripts of Marx, but this is probably the only way how in 2022 a new reading appears possible. There remains much more to disentangle. And then there is the issue of the Parzellenbäuer*in. Could they be part of this third class and could this explain their important role in the 18th Brumaire? This would be worth a closer look.