Clipping Essaym II: Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them

Let’s take a few steps back. Retracing Lorca’s project, I have tried to show that he (1) examines an aspect of popular culture, tapping into the rich archive of lullabies, which allows him to discover a wealth of artistic expression both complex and – in multiple ways – disenfranchised; a wealth inaccessible to any sort of viewpoint concentrating only on ‘established’ high art, or on questions of individual authorship, because these concepts are inextricably linked to political exclusions Lorca’s interest can detour; and that (2) his method consists in a particular kind of participatory observation, namely that he willingly and readily shares in the libidinal network woven by his objects. Just listening, here, becomes an entering into the ámbitos of desire that are the lullabies. Just as the mother-figure singing the lullaby called ‘adulterous’ is not necessarily adulterous herself, but cannot help but enter the logic of adultery, Lorca aims to enter the logics of the lullabies without necessarily having to sing a child to sleep. I then proceeded to identify two (broadly speaking) homoerotic relations; maybe a questionable move on the grounds of a text so invested in female expression, seeing that one of the two relations happens to be male homoeroticism.

But I think it is absolutely crucial to see that the mother-figure’s desire for the lover that is el cocois not essentially heteronormative, in other words: that Lorca can indeed partake in that desire even if el cocoremains identified as a masculine figure. The mother-figure’s desire is fundamentally shareable; it goes not only beyond the desire of the individual person taking her role in a specific lullaby-situation (the individual participates in an adulterous desire without being adulterous themselves), but also beyond the gender of its subject. Moreover, it is not all said that el coco must remain identified as masculine – surely, it makes no sense to accord to much importance to grammatical gender here, el coco is, after all, una abstracción poética.

A blur just below gender, or just outside gender’s door.

Which means that the mother-figure’s desire for el coco can be hetero-erotic, but it can also be a desire of female homoeroticism, or a desire of male homoeroticism.

The second homoeroticism, then, is a relation of abstract homoeroticism identifiable between Big Priest-Father of Control and el coco, and this homoeroticism is abstract precisely because although the gender of the first part is, in this case (unlike the mother-figure’s), defined (Big Priest-Father of Control is male no matter what), the gender of the second part is of no importance whatsoever. It is the relation between an abstract masculinity and an abstraction just below gender; but it is homoerotic because (1) there is a desire of the first towards the latter, and of the latter towards the first, and (2) the first and the latter are, on some level, identical: it is a desire from something towards something that is the same. This is the abstract homoeroticism between the Police and The Thing on the Doorstep, between the law and its beyond; it is the homoeroticism of N.W.A. wanting to fuck the police.

It is the abstract homoeroticism of the muchachos that risks to turn the mother-figure and the child into a vanishing third, like the fairies and the sirens, and el coco itself.

And it is the homoeroticism that deepens the abyss of el coco’s blurredness: it is so blurred you cannot know whether it is not, after all, simply Big Father of Control.

Like el papón denotates “Big Daddy” as well as el coco.

And as O.T. Genasis has famously explained, being in love with the coco rhymes perfectly well with wanting to fuck the po’po’ (from either “police” or papón). How would you know the difference?

I know nothing / fuck the po’po’

The man just outside the door could always be secret police. Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition.

And Big Daddy could be the only thing that can protect you. Someone who knows the drill.

Folding point (2) back into (1), I would like to stress, again, that these figures and relations are not any individual’s production, but elements of shared practices, repeatable and repeated like the syllable “co” in coco. Developing them is a matter of study, not of any sort of ‘immediate’ individual invention. They are what necessarily appears in any rigorous practice of just listening to (or watching, or smelling, or tasting – remember los dulces) socio-historical reality; they are a crucial by-product of any inquiry into popular culture, and the point of interest for Lorca’s scientific surrealism, convinced as it is that popular arrangements of desire are part and parcel of the material social infrastructure.

If we want to know how ‘real’ something is, Lorca seems to say, the crucial difference is not between “a fantastic beast” and “a physical thing”, but between “something that is repeatable and repeated across time” (like el coco, a cliché, a myth, un dulce, or a political structure; those are very real) and “something that exists only once” (like the Basílica de la Sagrada Família, or Un Chien Andalou; those are not very real). There are fantastic beasts repeated and shared (such as the Bogeyman) – those exist; and there are fantastic beasts barely (or not at all) repeated and shared (such as, say, Nagini) – those do not exist, which is to say the exist about as little as the Sagrada Família.

This might sound not very intuitive, but then, science is not there to simply restate what common sense thinks it already knows. But maybe it sounds less outrageous if I formulate it like this: if one analyses the social reality of the Western world, the Bogeyman (or Santa Claus) is to be considered, but Nagini (or the Sagrada Família) is of no importance (yet).

f one grasps the immense importance repetition has for the question of existence according to surrealist science, its fetishization of rhymes and mirrors becomes easily understandable.

Can you look into the mirror and then say it again?

This, obviously, is not without purchase on the question of genre in art.

Let me bluntly state what scientific surrealism says: if your worlds do not allow for fantastic beasts, you’re not doing realism; and if those beasts are not the secretion of a massive, authorless, and profoundly material socio-historical network, you’re not doing surrealism.

Now of course, you might neither want to produce realism nor surrealism, but rather Sci-Fi or your own branch of –ism nobody knows of yet – in this case, that statement is of no importance to you. But it is nevertheless interesting to ponder scientific surrealism’s standpoint because both capital-R Realism and capital-S Surrealism have developed strategies to do precisely the opposite of what it prescribes. The latter has plunged itself all too willingly into an aristocratism of imagination: a happy few allowed themselves indulge in literally whatever they came up with, pretending that overruling reason was a great feat of sorts, all while simultaneously looking down on everyone else, whom they considered chained not by material disenfranchisement, but by some idealist poverty of imagination. Instead of studying popular formulations of desire (as Lorca does in Las nanas infantiles), tracing patterns of repeated desire, they chose to loll in their own pseudo-profound individualist randomness, bemoaning the ‘lack of imagination’ capitalism (or secularism, or whatever) allegedly brought upon everyone except them. As a result, they managed to produce the (to my knowledge) only type of art directly intended for both jet-set-playboy-aristocracy and the bedrooms of culturally underprivileged students, and for absolutely nobody else.

Capital-R Realism (Bürgerlicher Realismus), meanwhile, employed what János Moser has called “die Hexe des Realismus” – Realism’s Witch, meaning more or less a fully-fledged poetics of “…but actually”: yeah, it looks like this is a demon, for the first two hundred pages or so, but actually it is ‘simply’ a psychotic person; yeah, it sounds like this is a ghost, for the first six chapters or so, but actually it is a woman we’ve shut away in the attic because she’s a bit annoying, so don’t worry; yeah, it looks like this is a human-bat hybrid, for the first ten minutes of the film, but actually it is a white male billionaire and it is really complicated with the city and him and responsibility, and he’s really troubled and it is really, really complicated, I mean, is there really a difference between him and the criminals he chases (we’re not talking about the ten or twelve billions he has that they don’t, we’re talking about metaphysical difference), and do the citizens of the city even realizethat they need him or are they faceless foggy morons we never ask? Or, in Moser’s prime example: Yes, we think she’s a witch, for the first two hundred pages or so, but actually it is just an old woman. Realism’s Witch, thus, is simultaneously the Realism Switch: choosing to implement a “…but actually” or not is like turning Realism on or off.

If I understand Moser correctly, this means, conversely, that all works (or at least: all literary works, with which his argument is concerned) start out outside of Realism. In default position, the Realism Switch is off.

And the main goal of Realism is to make everyone believe, in a feat of massive gaslighting, that it is by default on.

As long as Realism is not yet activated, we’re not simply elsewhere. We’re just below Realism, or right outside its door. Or rather, we’re just below genre, outside the door Realism, but also of the door of Surrealism, the door of Fantasy, the door of Sci-Fi.

Rondamos las habitaciones. We stalk around the houses.

Picture Goya, strolling through some Spanish landscape, at the dusk of the 18th century, kind of like an old man who’s a bit lonely and a bit hard of hearing. He’s not really old – in fact, he will live for about thirty more years – but the age is. And he really is almost completely deaf, due to an unknown cause; unknown to me, anyway. It might have been some kind of poisoning, or a complicated illness ravaging his eardrums. So he strolls through some Spanish landscape, indulging in a newfound interest in the ‘common’ people of Spain (he’s been employed at court for the past decades), watches some stuff (his eyes are still good, after all), chats with some folks, and maybe even makes a few offhand sketches here and there. Back home, certainly, he spends his time making etchings. He intends to sell them on the free market, leaving the commission-based model of his former work. He takes to wearing glasses, or else to paint himself while wearing them, maybe intending to stress the power of his eyesight: I’m a painter, who gives a shit about my hearing.

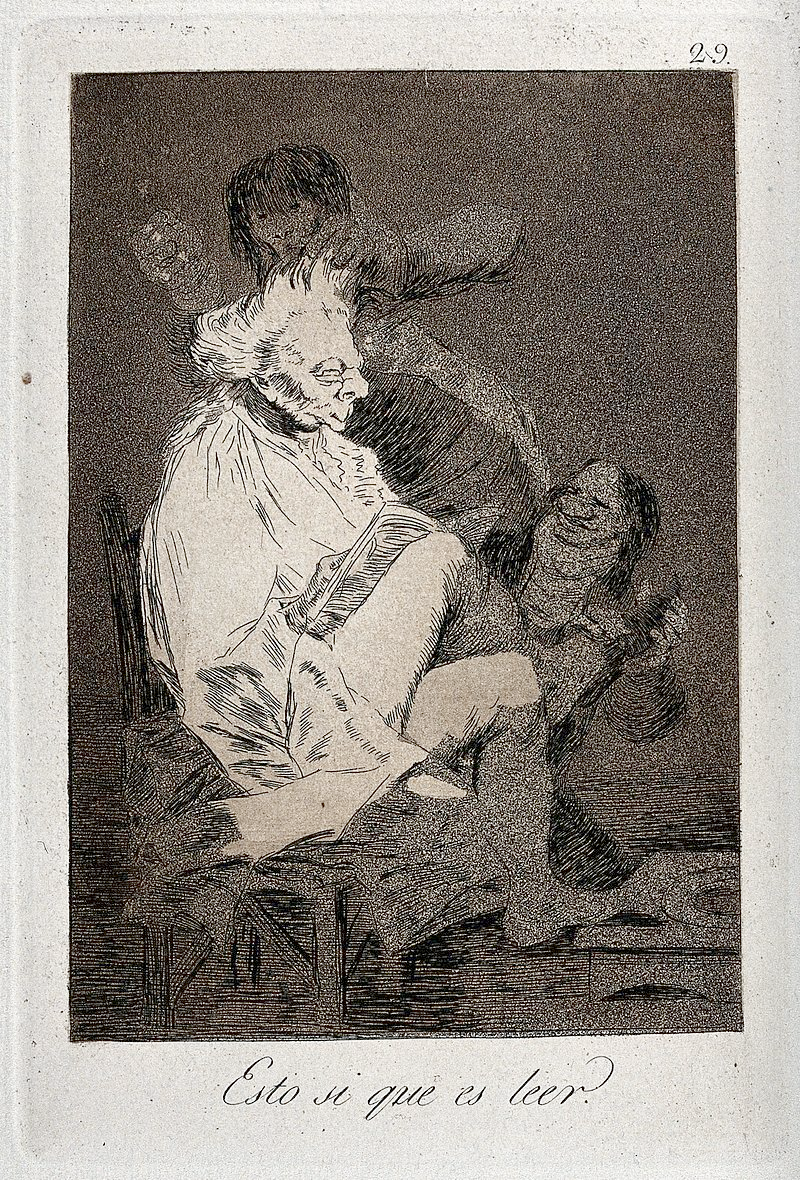

The etchings are disturbing, famously so; a long list of nightmarish images full of fantastical beasts and monsters. Now one could say, of course, that his newish interest in common social life and these etchings have not really anything to do with each other; that these images are simply what an artist slightly fed up with court painting might want to do for a change, namely letting his imagination run, and paint from the depth of his innermost imagination, illustrate, as it were, wholly personal dreams; dreams which would inevitably dark and menacing, seeing that our painter is anguished, ill, and lonely. The title of the etchings, Caprichos, might just support this thesis: these are flights of fancy, the favourite painter of the royal court keeping something of a personal diary on the side, moonlighting as a ghost train engineer; while on his official paintings, he documents Spanish (upper-class) life in the full bloom of his palette, in dashing colour, maybe with an uncanny atmosphere here and there, but certainly devoid of monsters.

But how would we square this notion of the Caprichos as a fundamentally private endeavour with his wish to sell them on the general market – surely a move quite opposite of the commission-based system of the paintings, which could be argued to be a lot more private than the open market? I suppose we couldn’t. Moreover, there are the etchings’ subtitles, which give a hint or a quasi-explanation of what we see on the image. And we realize that the images depict popular sayings, proverbs, jokes, rumours, and nursery rhymes, such as the one where el coco comes to eat the children. This is a fantasy, yes, or, more precisely, a desire; it is, in ways, a capricho, but it is not at all an individual flight of fancy, but a collective, shared one; a single graphic manifestation of a repeatable, popular, collective fantasy. Recall, also, that these are etchings, which means that these images are themselves extremely repeatable, intended for reproduction – as long as the plates hold, hundreds and thousands of copies can be produced. Seen from this angle, the Caprichos are an attempt to document a social phenomenon while being homologous to it, i.e. to share its structure of functioning: They document the circulating and repeatable libidinal rituals of a society on a repeatable medium sold on what Goya might consider the site which allows for the most intense circulation: the general publishing market. Why not just distribute them for free, you might ask; wouldn’t that allow for a lot more circulation still? The answer to that might at the same time be the explanation for Goya’s slightly enigmatic choice to make Capricho No. 1 (of 80) a self-portrait, with coat and top hat and all (and not in the slightly flamboyant court outfits he sported on earlier self-portraits): the artist as bourgeois.

Which is in and of itself not completely old-fashioned, boring, and complacent: This is 1799, after all. Bourgeois society is still kind-of-embroidered with revolutionary sentiment.

And hey, he has to make a living.

But now someone still holding fast to the first thesis – the Caprichos are not really social ethnography – might say: Ok, fair enough, but still, those are fantasies – and if shared ones; these nightmarish etchings are not portraying Spanish social life as it is, but as it imagines or fears itself to be; donkey-headed monks, birds with human heads sodomized by maids, imprisoned hobgoblins, and guru parrots are notpart of Spanish society, just of its cultural imagination. But I would answer, with Lorca, with scientific surrealism, that the ways in which a society thinks about the world – its fears, its hopes, in short: its desires – is not just one, but an essential part of that society.

It’s like someone illustrating the notion of a Dreiköpfiger Familienvater.

It is a question of seeing the layers of sense vertically amassed in a phrase or in a person, and horizontally distributed over a collective.

Through Goya’s spectacles, the individual is a pulsating construction zone, a bombed-out landscape, or a derelict housing project; offering nooks and corners for packs and swarms.

Over and over again, in these etchings, swarms appear, hovering just over ground, hunched in corners, or diving down from the clouds. Any shadow, here, can turn out to be a swarm, and any swarm can just as easily retire back into darkness. Faces are reflected in fur, in dust; doubled in fog and shades of grey. Smoke and mirrors.

Goya puts the prints on sale and then, like someone who realizes they’ve made a mistake, retracts them almost immediately.

Before settling with the title Caprichos, Goya had considered naming them Sueños. Dreams – or Sleeps, as in the title of the probably most famous image of the series, El sueño de la razón produce monstruos. Is it the sleep of reason or the dream of reason that produces monsters?

Y el que quiere saltar al sueño, se hiere los pies con el filo de una navaja barbera.

In the following twenty years, Goya will keep his interest in Spanish social life, transferring it over to painting, and yes, those paintings are indeed free of monstrous creatures. They are sometimes very violent – how could they not be, if they aim to document social life; Spain is waging war against Napoleonic France, after all, and Goya observes a battle-torn life. But crucially, he documents it in etchings as well, in the famous Desastres de la guerra, which, again, include no fantastic beasts.

It goes without saying that metaphorical monsters such as murderers, rapists, etc. do not count (yet); they’re not fantastic beasts, they’re just pathetic and embarrassing.

Just a bunch of scared junkies not making the call

The fact that Goya documents the war in etchings proves at least that he himself makes no distinction such as: paintings-official-documentary vs. etchings-private-fantastical. The Desastres make clear that Goya indeed considers etchings as a medium of socio-historical documentation.

And painting? Well, some time between 1810 and 1820, he creates this spectacular painting called El entierro de la sardina, “The Burial of the Sardine”.

It shows a dancing crowd.

I would argue that this painting smashes every distinction my imaginary interlocutor could have put up. It is a painting, not an etching, and if we assume, for the provisory sake of sanity, that the people depicted wear masks – and, getting some help by the title, we further assume that the painting shows the entierro de la sardina, a part of Spanish carnival routine, celebrated on Ash Wednesday, if we assume all of this (and why wouldn’t we?), the painting, indeed, documents Spanish social life. As the burial is a ritual, it is also part of a repeatable and repeated pattern.

And reality – of the social or the neurological kind – is a form of repetition.

There’s just one problem with this approach, with assuming that Goya is indulging in a bit of straightforward ethnography: where is the sardine? Well, buried, duh, you might say. It’s below the earth and people are dancing to celebrate its burial. But the ritual of el entierro de la sardina does not entail any burying below ground at all; rather, the sardine – usually a huge fish-like figure made of textile or paper – is burned in a huge bonfire. Goya’s painting, however, includes neither a fish-like puppet nor a fire. It’s just people dancing, and the most prominent ‘thing’ in the image is certainly the large darkish banner with the grinning face, which is even less of a sardine than the sort of thing that is usually burned as the namesake sardine.

True, the trees in the background look kind of set ablaze, but there’s no visible fire (rather, they look like a dark green fire). And what sort of sky is that anyway, coloured like those morbid timeless dusks Titian spreads out over his mythological sceneries or his portraits of monarchs at the edge of downfall (elsewhere, I have called them ‘extinction skies’). The mood of the crowd seems to be somewhere between a cultish party and an uprising. Dark rabble-vibes abound.

Of course, carnival is a violent feast, and stereotypically allied with confusion. If the sardine is absent, does it even matter? It’s a bizarre ritual anyway: The fish – a symbol of fast – is buried on Ash Wednesday as if that were the day the fasting season ends – yet it is, actually, the last day of the feast, on the eve of the fast. Perhaps this is the reason behind that Titian-like sky, drunk with historicity: This is an empire before the fall, it just happens to be the empire of carnival; and we see a populace foolishly burying what they believe to be that which falls, although it is them who fall and the fish who will triumph. It is their own burial they celebrate.

From the viewpoint of extinction, everything becomes a carnival.

Leave the face painted / A mask for the hereafter

Or, say, that the time of painting (not the time within the painting) is more important: let’s say we knew (we don’t), that El entierro was painted after 1813, thus after the expulsion of French Imperial rule and the restitution of King Ferdinand VII. As the French puppet king had temporarily prohibited the celebration of carnival, re-celebrating it would be connected not only to the ritualistic history of carnival itself, but also to the immediate political history of contemporary Spain: finally, we are again our own masters and can, once again, bury the sardine!

That political restitution, however, had very little positive effect for Goya’s life: after enjoying relative artistic freedom under French rule, Ferdinand VII. was quick to reinstall and intensify the old alliance of monarchy and the Inquisition, pushing his own powers to the point of absolutism and establishing a net of terror and torture.

das andere Mal als Farce

On self-portraits of that time, Goya drops the spectacles, preferring to depict himself as a grumpy ogre; and one can imagine him painting the Entierro and thinking: This is what you celebrate, you dumb fucks? Do you not see that there is no sardine? Is there any grey matter behind those stupid masks, is there anything you realize except this trivial feast pseudo-generously afforded to you by someone betraying, suppressing, hurting, and killing you; the illusory toys handed to you by Big Father Of Control? Did none of you expect the Spanish Inquisition?

It is a question of seeing the layers of sense vertically amassed, horizontally distributed, and then rhythmically put into motion. Of seeing collective desires transform and deface mass.

Or the sardine is, again, a vanishing third just like the fairy to the pair of mother-figure and child – something that exists only as something that has just disappeared: could it be that the pair of government and governed need, as their complement, an absent non-sardine to bury?

But this would mean that the entierro Goya paints goes well beyond the situation of the entierros de la sardina in general; that the entierro he depicts is not all restricted to the carnival, indeed, it is, on some level, not that feast at all (as made clear through the absence of the sardine). The carnival ritual, limited to one day once per year, buries a non-sardine, but one that is present. The feast Goya paints, however, is the feast celebrated without any need of the non-sardine being there.

The question, then, is whether this means that the feast painted by Goya is celebrated always except on Ash Wednesday (because that is when the feast with the present non-sardine is celebrated); or whether, conversely, the feast painted by him is celebrated every day no matter whether the non-sardine is present or not, thus turning all days into Ash Wednesdays – for the absent non-sardine must be buried every day.

YOU HAVE RECEIVED

ITEMS (0)

WEAPON 1x GOYA’S SPECTACLES

CREATURE -1x NON-SARDINE