Clipped Essaym

say the name

Before Surrealism became synonymous with individualist self-indulgence of the I’m-So-Random-kind – no, being able to do things without thinking is not the flex you think it is – it was something entirely different. Maybe it was, among other things, the fever-pitched ethnography exemplified by Federico García Lorca’s masterful Las nanas infantilesof 1928, a conference-length inquiry into popular lullabies of the writer’s native Spain, and a possible example or maybe forerunner of what I would like to call scientific surrealism.

When studying the country, Lorca writes, two things fascinate him more than everything else: las canciones y los dulces, the songs and the sweets.

Yes, yes, one can no longer think of Surrealism without thinking of World Wars and monocles, of extravagant vehicles full of fascists, of avant-garde grown stale, of laughable lo-fi psychoanalysis, of elephants melting under a masculinist sun, of moronic moustachioed monarch-impersonators.

But let me assume for a moment that Lorca was onto something here, that he exhibits an excellent taste in choosing his fascinations. Early on, he admits that he has no idea what he is doing, but he is willing to go daydreaming about sweets and lullabies, feeling that there is something that connects the two, that they are, on some level, two sides of the coin.

And he didn’t have Leïla Slimani’s Chanson Douce to help him; a profoundly disturbing novel translated into English as Lullaby, a word apparently – on some level – synonymous with what the French title literally means, sweet song. Well, he would have read it in Spanish anyway, where it is called Canción dulce.

[Q]uise saber de qué modo dormían a sus hijos las mujeres de mi país, he writes. I wanted to know how the women of my country put their children to sleep.

Let me also immediately note that this ethnographic interest has nothing to do with individualist fantasies whatsoever, not even with the low-key individualism in which the artist is the prophet expressing what is most general or most profound – no, this is an interest in a shared practice without any privileged authorship. Psychoanalysis hovers in the background, just as the classical view of capital-S Surrealism wants it to – it is a study on a practice concerning the child and the mother, after all – but this is not bourgeois psychoanalysis, it is not about and individual subject finding or creating symbols for an individual situation, it is psychoanalysis as the half-hallucinating reading of a massive infrastructure called ‘the lullabies, as they are sung in Spain’ (or the sweets as they are eaten).

This is what makes sweets more interesting than cathedrals, Lorca argues; the collected cathedrals of Spain are a fixed network of fixed and isolated buildings that each represent a fixed epoch in Spanish history; but all the songs sung and all the sweets eaten in Spain make up a huge libidinal infrastructure, a webbing of desires and anxieties spread out across the land, shared by the people, and shared by the epochs, as una canción salta de pronto de ese ayer a nuestro instante, viva y llena de latidos como una rana – a song suddenly jumps from its era [of composition] into our moment, alive and palpitating like a frog.

Singing a lullaby, then, means being embedded in (at least) two immense webbings; one spatial, spread out across Spain, and one temporal, spread out across history.

Lorca begins with an overview of European lullaby traditions, identifying the grandes telones grises, the great grey curtains of Middle Europe, where lullabies are soft and monotonous (and uninteresting), putting the child to sleep employing a sort of soft pressure through boredom, as well as the cloudy distant sadness of Eastern lullabies. In contrast to both of these traditions, Lorca says, the Spanish lullaby is crisp, explicit, and often violent or otherwise menacing.

Y el que quiere saltar al sueño, se hiere los pies con el filo de una navaja barbera. And those who try to jump into sleep cut their feet at a razorblade.

This is not to say that Spain is, as the cliché wants it, a quasi-archaic civilization prone to cruelty and darkness before all else. Spain has a wealth of happy songs to offer, Lorca argues, it just happens that they save the bloodiest ones for their little children. At first sight, this seems not very intuitive.

But at second sight, one must remember the situation of the lullaby, its material conditions, if you like: No debemos olvidar que la canción de cuna esta inventada (y sus textos lo expresan) por las pobres mujeres cuyos niños son para ellas una carga – we must not forget that the lullaby was invented (and their lyrics express that) by poor women to whom their children were a burden. And further: Cada hijo, en vez de ser una alegría, es una pesadumbre, y, naturalmente, no pueden dejar de cantarles, aun en medio de su amor, su desgano de la vida. Every child, instead of being a joy, is a sorrow, and, naturally, [the women] cannot help but sing, in the middle of their love, the pain of their life.

So much idiocy has been said about the relationship of surrealism and psychoanalysis that I am unable to say what I would like to say here: that the lullaby Lorca calls the ‘Spanish’ lullaby is analytic in nature. Rather than the grey curtains of the Middle European or the melancholic, but gracefully covering snow of the Russian lullaby – yes, I forgive him all this nationalism, his point is interesting enough – the Spanish lullaby is a medium where the relationship between the child and the mother-figure is analysed through its expression, that is to say, with the full thrust of its problems. This can include wishfully imagining, in a song addressed to a little child, one’s own death in order to escape the reproductive violence exerted by the child’s father, such as in this Asturian example:

Este neñín que teño nel collo

E d’un amor que se tsama Vitorio,

Dios que mo deu, tseveme llougo

por non andar con Vitorio nel collo.

This child that I am stuck with

Comes from a lover called Vitorio,

God gave him to me, may God take me away

So I no longer have Vitorio breathing down my neck.

I write ‘mother-figure’ instead of mother because Lorca makes the point that if the mother is not poor and therefore maybe doesn’t think of her child as a burden, she will employ a poorer woman as a nanny. Thanks to the nanny, the wealthy woman can enjoy her child as a part-time, holiday-like pleasure activity free of rancour towards the child, but this also means that the person singing the lullaby will be the nanny – the poorer woman, whose social position will again be adequately reflected in the violence of the lullaby’s text.

Again, this will be quite precisely Slimani’s territory, in Chanson Douce.

What Lorca discovers, then, is something like an archive of (broadly speaking) female expression; he steps into a reservoir of creative endeavour undertaken by people for whom the canonical artistic venues remained, in different ways, foreclosed. This is also, I think, what differentiates his project from similar ethnographic studies on (Spanish) music, entertained by the likes of Manuel de Falla et al., who never realized that geographic regions are fundamentally intersected by social regions not perfectly identical to the former; that is to say, folklore ethnographers were able to see that the popular music of Asturias was different to the popular music of Granada, and that one might unfairly be regarded as primitive whereas the other has become, for certain reasons, the hallmark of sophistication and the essence of ‘Spanish’ national character. But they never became aware of the fact that a male artist from the region called primitive might still be endlessly more privileged than a female artist from the region called sophisticated.

Lorca thus makes first steps at transforming what were studies on folklore – which aimed to muscle the sum of regional quaintnesses into capital-N Nationalcharakter – into studies on ‘popular culture’.

Part of this, Lorca seems to say, is simply listening.

Todos los trabayos son

para las pobres muyeres,

aguardando por las noches

que los maridos vinieren.

Unos venien borrachos,

Otros venien alegres.

Otros decien: Muchachos,

vamos matar las muyeres.

All the travails rest

On us poor women,

Who wait all evening

For our husbands to return.

Some come home drunk,

Others come home happy.

Still others say: Guys,

Let’s go kill the women.

Yes, Lorca shares an interest in the characteristic of ‘Spanish’ song, but his ambition to make his study a sort of advertisement for Spain is relatively faint. The ‘Spanish’ situation is only an entry point into a simultaneously more general and more specific situatedness, namely that of the mother-figure-and-child-relationship, looked at through the lens of a disenfranchised position. The lullaby called ‘Spanish’ is analytical enough to provide that lens.

If less idiocy had been said about the relationship of surrealism and psychoanalysis, I would also mention here the subterranean similarity – on some level – of Lorca’s project and Freud’s, insofar as they are both European men who, at the beginning of the 20th century, come up with the idea that it might be worth to, for once, just listen to what women say (of course, Freud then drowns everything in his ambition to craft a Big Huge Explanation Scheme out of it).

And both are clever enough to realize that just listening – listening that is, as Heather Love’s pun goes, just – will mean taking all kinds of detours.

Of course, the lullabies discussed by Lorca are not simply reports documenting immediate material factuality. Rather, and importantly, they express straightforward reality as well as wishes and fears – that is to say, they eventually map out entire regions of the affective landscape that makes the mother-figure, including all types of wishes and fears and flights of fancy. Lorca breathlessly reports their different forms, sometimes he is visibly confused, sometimes he contradicts himself; he has all the markings of someone stumbling unto a domain of knowledge new to them.

He leaves the impression of someone standing in front of a huge map mounted on the wall, and pushing little red pins it at places, sometimes connecting two with an equally red thread, sometimes making a small drawing somewhere, looking at the audience as if they were, eventually, those with the answers.

So he lists. Songs which paint a foreign and sometimes fantastic landscape, and place a stone hut there, imagining a future for both mother-figure and child in the peaceful calm of that hut; songs which tell sad stories of children lost on the road or stolen from their mothers, comparing the privileged bliss of the child finding itself in safety, with someone to lull them to sleep; songs in which the singing figure assumes the position of the child and speaks, in first person, about falling asleep – maybe dramatizing what is true, Lorca says, of the lullaby setting in general, namely that it includes some sense of mirroring, with the mother-figure watching the child, and the child watching the mother-figure:

Hay una relación delicadísima entre el niño y la madre en el momento silencioso del canto. El niño permanece alerta para protestar el texto o avivar el ritmo demasiado monótono. La madre adopta una actitud de ángulo sobre el agua al sentirse espiada por el agudo crítico de su voz.

It is a most delicate relationship between the child and the mother, in that silent moment of song. The child remains alert and ready to protest against the text or enliven a rhythm that has grown all too monotonous. The mother adopts the attitude of someone perched over a body of water, who feels observed by the most acute critic of voice.

This last description might give a bit of pause. Let me tell you what I think it says: It characterizes the child as a body of water, insofar as the one perched above it (the mother-figure) feels observed, watched. The sentence leaves open whether that observing is done by the mirror-image reflected on the water’s surface (which would mean, in accordance to the lullabies wherein the mother-figure adopts the viewpoint of the child, that the “acute critic of voice” is the mother-figure herself as reflected on the surface of the child – she watches her reflection as in a mirror and is thus, in turn, watched by it); or whether that acute critic lies somewhere beneath the surface, beyond the reflected surface image, in the (impenetrable?) depths of the dark waters, or of the child’s mind, respectively. I think it also riffs on the fact that a water surface is an excellent carrier of sound, stressing once again that the mother-figure and the child share a rhythm (against which the child might protest by, for example, introducing a more lively pattern), each reverberating off the other, like a mutual rippling on the face of waters.

Repetitions everywhere, the child reflecting the mother-figure, and vice versa, in the repetitive rhythm of the lullaby.

The hook gon’ be / what it is

It could also be that the “most acute critic of voice” is a third character, neither the mother-figure nor the child, but someone alluded to or invented in the interplay of the two first characters.

Such an idea could be supported by other parts of Lorca’s text. A particularly enigmatic passage is concerned with the role of the ‘fairy’: Stating that he has kind of seen a fairy in the bedroom of his younger cousin back in 1917, he claims that the presence of fairies is a necessary part of the successful lullaby – only to close the passage by saying that [a]l hablar incidentalmente de las hadas cumplí con mi deber de propagandista del sentido poético: by casually talking about fairies, he has fulfilled his duty as propagandist of poetic sentiment. Is this irony, a wry joke about the expectations towards him, the surrealist poet? Or is it, rather, the most important remark in all of his conference – the moment of full methodological disclosure: 'This is what this is about; this talk about Spanish lullabies is just a long and exacting employment of poetic sentiment, this is ethnography as a dream?'

Be it as it may, it is clear that the fairies are the complement to a double rhythm:

Después del ambiente que ellas crean hacen falta dos ritmos: el ritmo físico de la cuna o silla y el ritmo intelectual de la melodía. La madre traba estos dos ritmos para el cuerpo y para el oído con distintos compases y silencios, los va combinando hasta conseguir el tono justo que encanta al niño.

In addition to the ambient created by [the fairies], two rhythms are needed: the physical rhythm of the cradle or chair, and the intellectual rhythm of the melody. The mother[-figure] assembles these two rhythms for the body and the ear by establishing different paces and rests; combining them until she finds the right tone to enchant the child.

Maybe one could say, then, that the fairy is a type of vanishing third – [Vi la hada] como el gran poeta Juan Ramón Jiménez vio a las sirenas, a su vuelta de América: las vio que se acababan de hundir, Lorca claims, I saw the fairy like the great poet Juan Ramón Jiménez saw the sirens, on his return from America: he saw them just after they went under – added, maybe necessarily, to the two characters mother-figure and child. As they establish an at least doubled double rhythm, they complement or condition the existence of something third, an existence at the very point of just-gone-under, siren-like: think of the song of the siren, here, and of that most acute critic of voice hidden in the body of water, and of that crucial indecision whether that critic is a mirroring on the surface or something in the depth; an indecision which could maybe be reframed by saying that the most acute critic of voice se acaba de hundir, has just gone under and is readable only as a shiny and foamy ripple on the surface, a reflecting mirror of what is perched above, and the index of an indeterminable presence in the depth.

More prominent, however, and in ways more explicit, are Lorca’s examinations of lullaby lyrics that include a third character, whether as an object or as addressee.

He approaches the topic with a degree of caution; or maybe his circumnavigating style betrays slight confusion. First, he talks about the character of el coco, the Spanish equivalent to the bogeyman, and speaks about how it is the fact of being desdibujo, blurred, that makes el coco so powerful a figure. Precisely because it is blurred, el miedo que produce es un miedo cósmico, the dread it produces is a cosmic dread. Although ronde las habitaciones, he stalks around the house, el coco does not enter; it remains an entity that stays, as it were, just below shape; quite like the fairies and the sirens always just below the surface. If the fairy and el coco share this aspect of submersion, always just gone under, always just around the corner, right outside the door, they nevertheless function differently insofar as the fairy represents immediate calm to the child, whereas el coco is menacing.

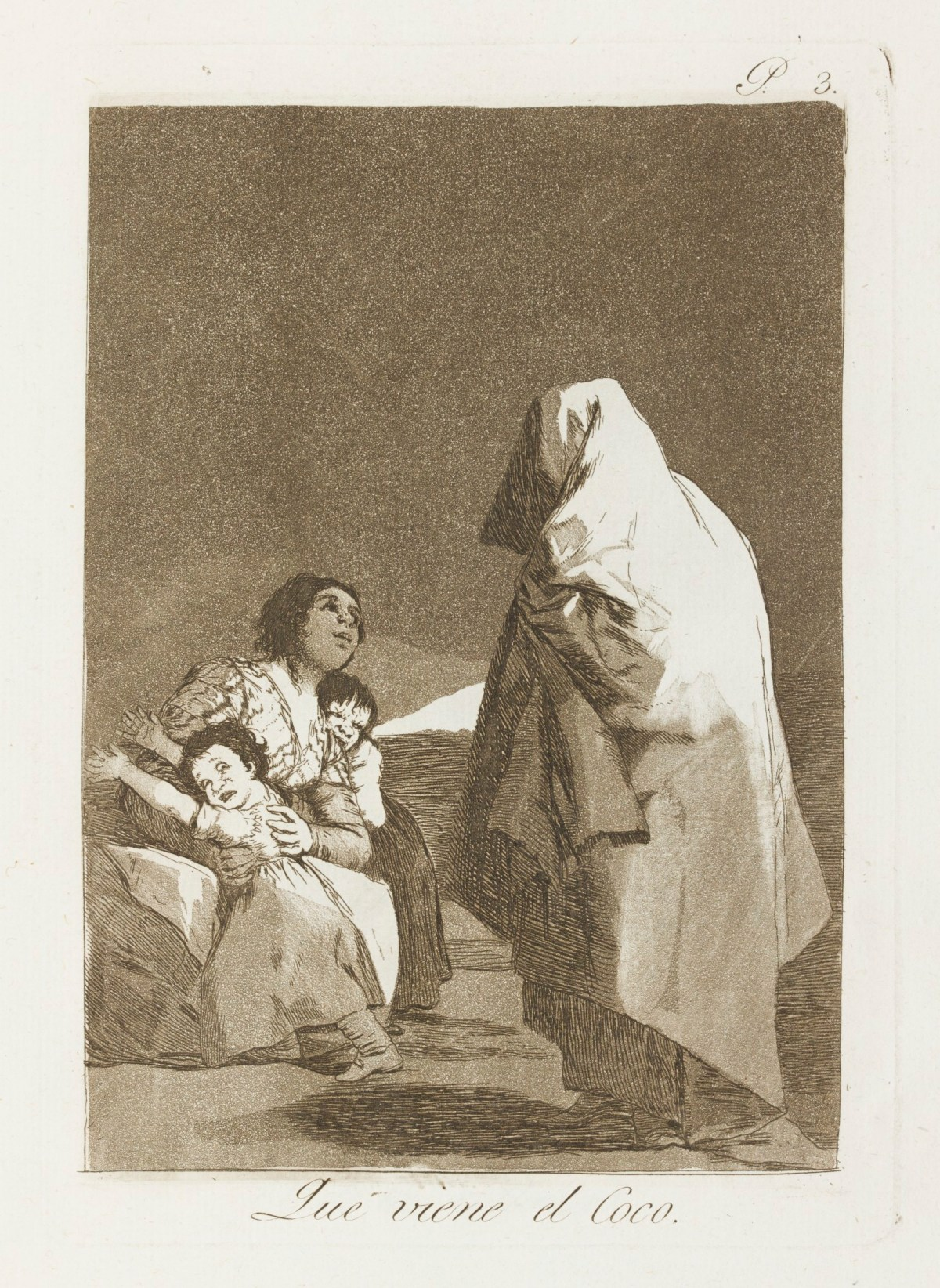

Lorca does not quote the most famous of Spanish nursery rhymes featuring el coco, captured by Francisco Goya in a terrifying etching:

Duérmete niño, duérmete ya...

Que viene el Coco y te comerá.

Sleep, child, sleep now…

Else el Coco comes and will eat you.

That heap of textiles, just above, and then just below shape.

Lorca then proceeds to quote nursery rhymes where the mother-figure imagines all sorts of fantastical landscapes, the aforementioned silent valleys and peaceful alps with their protective stone huts and their loneliness, with mythical cows and sheep, and so on, and so forth; and then about those where the mother-figure adopts the viewpoint of the child; and then he talks about those nursery rhymes which frame the child as an orphan or as the last being on an empty, lifeless earth, in which the mother-figure basically and paradoxically takes herself out of the equation through song, weaving a situation of absolute solitude in a setting of twoness – and only then comes back to the motif of the explicitly mentioned third character, which suggests that he saw no relation between the fairies and el coco on one hand, and those latter lyrics on the other.

Nos queda, sin embargo, he begins, por ver un tipo de canción de cuna verdaderamente extraordinario. But we still have to examine a truly extraordinary type of lullaby. And he further says that examples of this type can be found in Asturias, Salamanca, Burgos, and León, that, indeed, it belongs to no particular region, but is a type circulating (corre) all over the North and the Centre of Spain. Es la canción, he finally writes, de cuna de la mujer adúltera que cantando a su niño se entiende con el amante. It is the lullaby of the adulterous woman who converses with her lover all while singing to her child.

This is the first example he gives:

El que está en la puerta

que non entre agora,

que está el padre en casa

del neñu que llora.

Ea, mi neñín, agora non,

ea, mi neñín, que está el papón.

El que está en la puerta

que vuelva mañana,

que el padre del neñu

está en la montaña.

Ea, mi neñín, agora non,

ea, mi neñín, que está el papón.

The one who is at the door

May not come in now,

For the father is at home,

The father of the crying baby.

Oh, my child, not now,

Oh, my child, the father is here.

The one who is at the door,

May he come back tomorrow,

When the father of the baby

Is up in the mountains.

Oh, my child, not now,

Oh, my child, the father is here.

Truly extraordinary type of song, he says. Spread over half of Spain. And of course, it is an interesting organization, the woman nursing the baby while talking about someone who is not the baby’s father. No quiero decir, sin embargo, que todas las mujeres que la cantan sean adúlteras; pero sí que, sin darse cuenta, entran en el ámbito del adulterio, Lorca argues, I don’t mean to say that all the women who sing this lullaby are adulterers; but that if they do, they enter – if they want it or not – the logic [ámbito; realm] of adultery. This is a clever remark, in keeping with a type of thought he entertains all through his argument, namely the entering into logics without necessarily intending to. As the mother-figure sings to the child, different logics traverse them, and they become parts of different organizations, allying themselves with fairies and bodies of waters, with remote stone huts, and, in this case, with an illicit lover who may not come in as long as the child’s father is present.

Yet for reasons obscure, Lorca makes no connection between this type of lullaby and that of el coco; remains (wilfully?) blind to the structural similarity between the two. It seems obvious to me that El que está en la puerta / que non entre agora – the one who is at the door / may not enter now – is a possible formulation of the ‘rule’ Lorca establishes for el coco: Nunca puede aparecer aunque ronde las habitaciones; he is not allowed to appear although he roams around the houses (the agora of the lullaby is of course eternal, as it will be in force each and every time it is sung, the mañana never comes). Indeed, Lorca even ends his survey of the ‘adulterous’ lullaby with the following statement: Después de todo, ese hombre misterioso que está en la puerta y no debe entrar es el hombre que lleva la cara oculta por el gran sombrero, con quien sueña toda mujer verdadera y desligada. After all, that mysterious man who is at the door and must not enter is the man with a face hidden under a large hat, of which every true and liberated woman dreams.

This not a dream it's a memory

If my Spanish doesn’t fail me completely, Lorca’s phrasing leaves it open whether all true and liberated women dream of the man or just of his large hat. Maybe the man and his clothing are not really different things at all; maybe the man is, in sum total, just a heap of textiles, of the sort of dark folds that make up Goya’s coco. And maybe, just maybe, Lorca’s heavy generalization – toda mujer – betrays the fact that at this point of his argument – un tipo de canción de cuna verdaderamente extraordinario, he says – he is perched over his object like the mother-figure over the child, and is reflected; that, in other words, when talking about toda mujer, he first and foremost includes himself.

This is certainly a little bit aggressive a reading of the complicated politics of Lorca’s phrasing, the ways his formulation both fiercely attacks and resonates with the contemporary Spanish Catholic politics and proto-Clericofascist attitudes specifically, or both critiques and repeats male stereotyping of women (toda mujer desligada; all liberated women). And I also wouldn’t defend my reading purely on the grounds that Lorca obviously knew about the social illicitness of his homosexuality – that his desire was, from the standpoint of the hegemonic moralism of his time, fundamentally adulterous – and that he was, with good reason, anguished about it, fully conscious of the amount of homophobia he was facing (indeed, his homosexuality is considered to have played a major role in his eventual murder by fascist militia). To the anguished lover, the desired person is a source of both desire and fear – the lover who must not enter because “the father is in the house” (está el padre en casa) is the lover as el coco, and el coco as the lover. The cited nursery rhyme plays attains a doubled double meaning in this context: está el padre en casa could be translated as “the priest is in the house” – thus, the lover must not enter. This is the priest of Clericofascism specifically, but also of Catholicism in general, and a metaphor for conservative institutions altogether, the punishing Big Father Of Control.

Padre del neñu que llora. Father of the child that cries.

In turn, ea, mi neñín, que está el papón leaves open whether the mother-figure employs papón as the augmentative form of papi: “Oh, my child, Big Daddy’s here”, restating está el padre en casa in terms more openly mixing erotic and authoritarian dimensions; or whether papón rather denotes el papón, a terrifying figure from Castilian mythology intended to scare children, indeed, the Castilian version of el coco. Ea, mi neñín, que está el papón would then not (only) be talking about Big Father of Control, but (also) about the lover outside, the man (?) with the hidden face who must not enter and who is identical to el coco, to that blurred It.

So abstract is the blur that is el coco, Lorca says earlier, that the fear it evokes is a cosmic fear, but it is also so abstract that its characteristics will depend almost exclusively on the imagination of the child – y puede, incluso, serle simpatico. One can even grow to like it.

A possible translation of the nursery rhyme, then, would look something like this:

The one who is at the door

May not come in now,

For Big Priest-Father Of Control is home,

The father of the child that cries.

Oh, my baby, not now,

Oh, my baby, el coco is here.

On Goya’s etching: The terror of the child in front, the anger of the child in the back, and the expression on the mother-figure’s face – something between relief, expectation, and bliss.

Framed like this, I hope it becomes clear that Lorca places himself in the position of the mujer not because of his homosexuality, but because everyone reading or hearing the nursery rhyme enters, to use Lorca’s own formulation, the realm (ámbito) of a desire in which eroticism and fear are as infinite and indistinct as ‘gender’ falls apart in reflecting mirrors, shapes, and bodies of water. Not least of all, the dream of el coco is, no matter the dreamer, a landscape of a super-individual homoeroticism – isn’t the mother-figure only the reporter, here, of a relationship between two masculine figures, the (grammatically) masculine coco and the (politically) masculine Big Priest-Father of Control? Isn’t Lorca, in his fascination for this canción de cuna verdaderamente extraordinario following the singing mother-figure into a realm where he can turn into her in order to follow his desire for el coco, and am I not, in a way, and in turn, following Lorca?

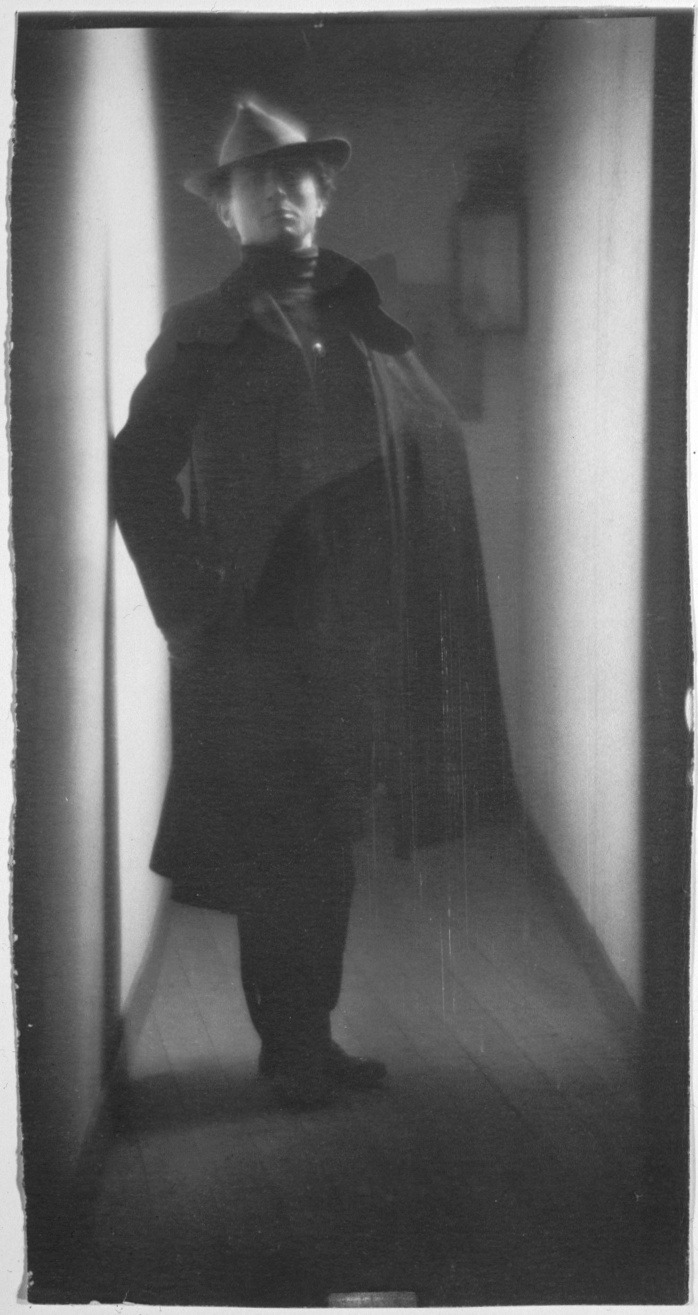

And yes, I’m writing all of this partly as an attempt to dive into my intense attraction to this portrait of Edward Steichen:

But I think this text is not me trying to find the most laborious way to say that I couldn’t say what’s stronger: my desire to fuck Steichen or my desire to become him (although I indeed couldn’t).

I only try to say that where el coco – the Bogeyman, le Croquemitaine, der schwarze Mann – is involved, one enters, inadvertently or intentionally, and without any importance accorded to one’s gender, a realm of homoeroticism –

The man in black fled across the desert, and the gunslinger followed.

– but I do not try to say that this is everything there is – indeed, that would be absolutely bland, abstract homoeroticism is really nothing special, it would be easy to argue that it is the cornerstone of that thing called Western civilization; rather, said homoeroticism is only a symptom of a much more complex array of desires, where it is infinitely easier to identify desires than to identify their subjects, and if only because the desires keep changing the subjects, switching between them or transforming them.

And such arrays, I would argue, are the realm of this small-s, 'scientific' surrealism à la Las nanas infantiles. This is where it thrives, because surrealism is convinced that it in such realms, it can develop something like a science; that it can cartography with exactitude any landscape as long as it is a landscape of (1) shared and (2) transformative desires rather than places or subjects; much like Lorca documents not so much a geographical Spain nor a Spain of ‘literary history’, asking which text has been authored where and by whom, but an affective Spain as a network of collective desire-formulations (for sleep, for peace, for a lover, for el coco) in which remote stone huts grow in undiscoverable non-Euclidian valleys, where nannies turn into children and children into water.

And what about the sweets? Well, they belong to the bees.

YOU HAVE RECEIVED:

ITEMS (2)

CHARACTER (LVL 1799) 1x EL COCO (GOYA VERSION)

CONCEPT (WEAK: DIFFUSE) 1x SCIENTIFC SURREALISM

TEXTS (2)

LEILA SLIMANI: CHANSON DOUCE

FEDERICO GARCIA LORCA: LAS NANAS INFANTILES