Clipped Essaym VI: Beelines

For part I-V, see here, here, here, here, and here, respectively.

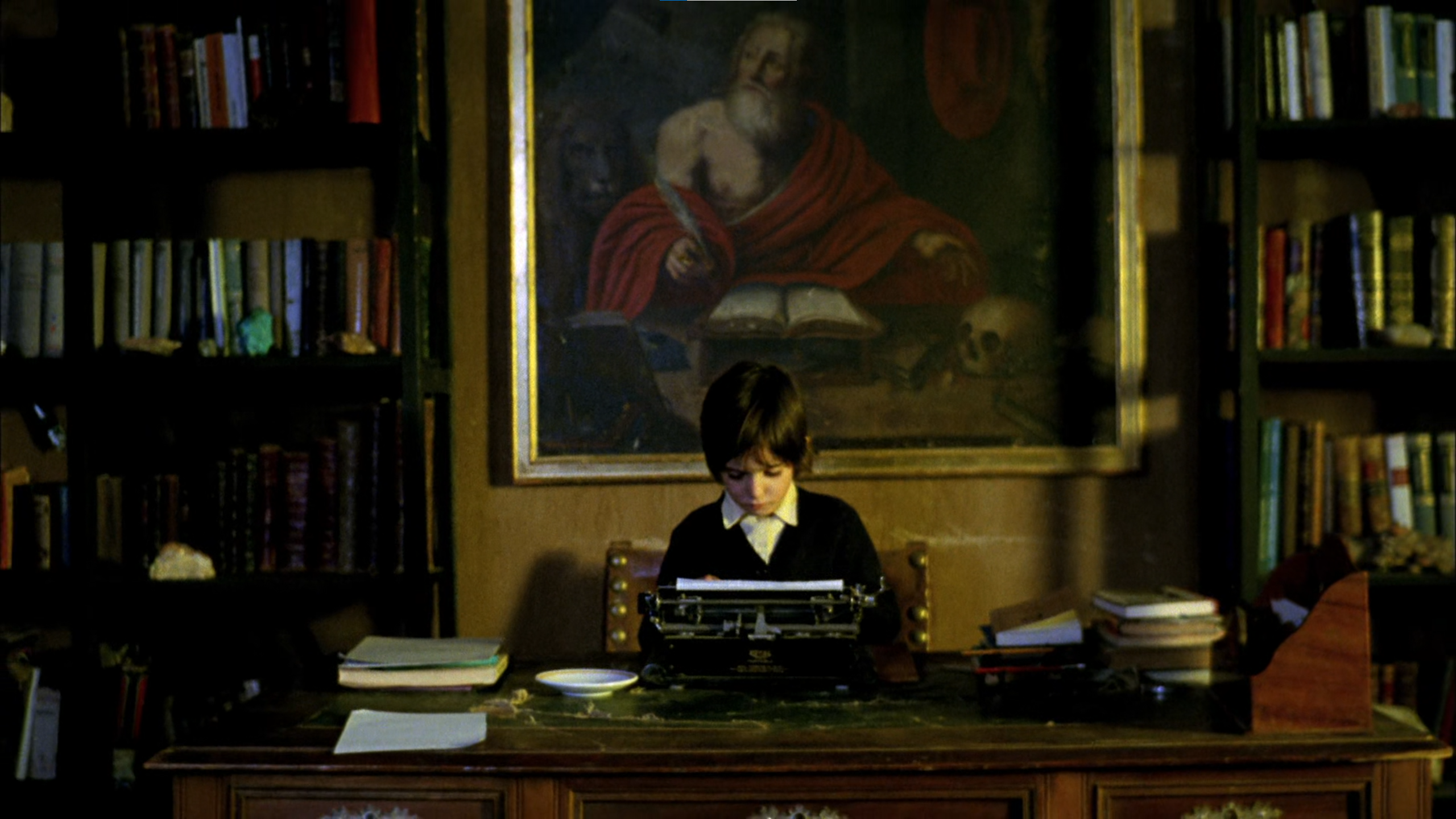

So what is the appearance of the monster at the end of El espíritu de la colmena doing, exactly? It does not mean that the monster is in any way 'more real' or 'more realistic' than the refugee, or Franco, or Teresa, or the world, or the bees, or the spirit. It only means that, just like the judgment over what Fernando is really writing, the judgment over the degree of reality accorded to the film's aspects remains suspended until the end. There is no dénouement at all, certainly not in the sense of a twist in the plot that hits like a lightning strike – rather, as I tried to argue, the appearance of the monster forces us to realize that the plot is untwisted throughout. Fernando might be re-writing Maeterlinck, but he also might simply quote him in a scholarly way; the footsteps overheard by the girls might be footsteps of the father, but (now we know) they might also be the footsteps of the monster; the refugee might be the spirit, or the monster might be the spirit, or both, or neither; the refugee might be the addresse of Teresa's, or not; the monster stepping out of the woods might be as real as Ana, or an illusion produced by her eating a psilocybin mushroom found in the woods.

What does it mean to return to the film's title, now? How does all of this relate to the spirit of the hive? Let's check out what Maeterlinck writes, apart from the passage written (down) by Fernando, in which the term of the ésprit de la ruche does not appear. The chapter in question is the third of La vie des abeilles, titled L'essaim (the swarm). I will give you the first approach of a definition in French first, in order to evoke some of the specific sound of Maeterlinck's text, and then the English translation:

"L'ésprit de la ruche", où est-il, en qui s'incarne-t-il? Il n'est pas semblable à l'instinct particulier de l'oiseau, qui sait bâtir son nid avec adresse et chercher d'autres cieux quand le jour de l'émigration reparaît. Il n'est pas davantage une sorte d'habitude machinale de l'espèce, qui ne demande aveuglément qu'à vivre et se heurte à tous les angles du hasard sitôt qu'une circonstance imprévue dérange la série des phénomènes accoutumés. [...] Il dispose impitoyablement, mais avec discrétion, et comme soumis à quelque grand devoir, des richesses, du bonheur, de la liberté, de la vie de tout un peuple ailé. Il règle jour par jour le nombre des naissances et le met strictement en rapport avec celui des fleurs qui illuminent la campagne. Il annonce à la reine sa déchéance ou la nécessité de son départ, la force de mettre au monde ses rivales, élève royalement celles-ci, les protège contre la haine politique de leur mère, permet ou défend, selon la générosité des calices multicolores, l'âge du printemps et les dangers probables du vol nuptial, que la première née d'entre les princesses vierges aille tuer dans leur berceau ses jeunes soeurs qui chantent le chant des reines. D'autres fois, quand la saison s'avance, que les heures fleuries sont moins longues, pour clore l'ère des révolutions et hâter la reprise du travail, il ordonne aux ouvrières mêmes de mettre à mort toute la descendance impériale.

What is this "spirit of the hive"—where does it reside? It is not like the special instinct that teaches the bird to construct its well planned nest, and then seek other skies when the day for migration returns. Nor is it a kind of mechanical habit of the race, or blind craving for life, that will fling the bees upon any wild hazard the moment an unforeseen event shall derange the accustomed order of phenomena. [...] It disposes pitilessly of the wealth and the happiness, the liberty and life, of all this winged people; and yet with discretion, as though governed itself by some great duty. It regulates day by day the number of births, and contrives that these shall strictly accord with the number of flowers that brighten the country-side. It decrees the queen's deposition or warns her that she must depart; it compels her to bring her own rivals into the world, and rears them royally, protecting them from their mother's political hatred. So, too, in accordance with the generosity of the flowers, the age of the spring, and the probable dangers of the nuptial flight, will it permit or forbid the first-born of the virgin princesses to slay in their cradles her younger sisters, who are singing the song of the queens. At other times, when the season wanes, and flowery hours grow shorter, it will command the workers themselves to slaughter the whole imperial brood, that the era of revolutions may close, and work become the sole object of all.

The ésprit de la ruche is thus, as I briefly outlined in part V, an ominous force not behind, but within the activitiy of the hive; it is either exactly coincident with the sum of every single activity in the hive (and only that, and impossible to formulate on any lower level, like "leading group of bees", "this or that bee alternatingly", "the queen", "all the workers"), or completely distinct from every single bee, utterly outside of all bee-ness, and all the more alien (there is a hive, but there are no bees in it).

And further – I will quote at length, because it is worth it, but only in English, lest this gets way too long:

The "spirit of the hive" is prudent and thrifty, but by no means parsimonious. And thus, aware, it would seem, that nature's laws are somewhat wild and extravagant in all that pertains to love, it tolerates, during summer days of abundance, the embarrassing presence in the hive of three or four hundred males, from whose ranks the queen about to be born shall select her lover; three or four hundred foolish, clumsy, useless, noisy creatures, who are pretentious, gluttonous, dirty, coarse, totally and scandalously idle, insatiable, and enormous. But after the queen's impregnation, when flowers begin to close sooner, and open later, the spirit one morning will coldly decree the simultaneous and general massacre of every male. It regulates the workers' labours, with due regard to their age; it allots their task to the nurses who tend the nymphs and the larvae, the ladies of honour who wait on the queen and never allow her out of their sight; the house-bees who air, refresh, or heat the hive by fanning their wings, and hasten the evaporation of the honey that may be too highly charged with water; the architects, masons, wax-workers, and sculptors who form the chain and construct the combs; the foragers who sally forth to the flowers in search of the nectar that turns into honey, of the pollen that feeds the nymphs and the larvae, the propolis that welds and strengthens the buildings of the city, or the water and salt required by the youth of the nation. Its orders have gone to the chemists who ensure the preservation of the honey by letting a drop of formic acid fall in from the end of their sting; to the capsule-makers who seal down the cells when the treasure is ripe, to the sweepers who maintain public places and streets most irreproachably clean, to the bearers whose duty it is to remove the corpses; and to the amazons of the guard who keep watch on the threshold by night and by day, question comers and goers, recognise the novices who return from their very first flight, scare away vagabonds, marauders and loiterers, expel all intruders, attack redoubtable foes in a body, and, if need be, barricade the entrance.

This is ripe with political imagery, and it is obvious how it would be tempting to read the appearance of this text in El espíritu de la colmena as a hint to read the film itself as a political allegory; with a dark and alien force – the fascist government with its "sweepers", its "guard", always ready to "question comers and goers", to "scare away vagabonds, marauders and loiterers, expel all intruders" – absently governing the activity in the family house, leading to a life lived in compartmentalization and isolation, in silence and non-communication, repressed, regretful, and anxious. Or, indeed, to say that all of fascist Spain is the hive, governed by an absent evil spirit that keeps the whole country under its heavy thumb, by an inexplicable and unreadable force that turns even the caudillo himself into just another servant of its will, just as Maeterlinck describes that "with this queen of ours it happens as with many a chief among men, who though he appears to give orders, is himself obliged to obey commands far more mysterious, far more inexplicable, than those he issues to his subordinates."

But Maeterlinck's spirit of the hive is explicitly not simply a metaphor for something specific – like a position, caudillo, duce, Führer – in human politics. In stark opposition to who is in some way his predecessor in the French language, Jules Michelet with his L'insecte (1858) and its study of 'bee politics', Maeterlinck is not interested in drawing parallels between apian and human nature – and least of all in Michelet's judgmental, moralizing mode. Rather, l'ésprit de la ruche is, for the most part of Maeterlinck's text, the emblem of an enigma, the representation of an end of representability, if not always in its effects, at least always in its origin and its ends.

Finally, it is the spirit of the hive that fixes the hour of the great annual sacrifice to the genius of the race: the hour, that is, of the swarm; when we find a whole people, who have attained the topmost pinnacle of prosperity and power, suddenly abandoning to the generation to come their wealth and their palaces, their homes and the fruits of their labour; themselves content to encounter the hardships and perils of a new and distant country. This act, be it conscious or not, undoubtedly passes the limits of human morality. Its result will sometimes be ruin, but poverty always; and the thrice-happy city is scattered abroad in obedience to a law superior to its own happiness. Where has this law been decreed, which, as we soon shall find, is by no means as blind and inevitable as one might believe? Where, in what assembly, what council, what intellectual and moral sphere, does this spirit reside to whom all must submit, itself being vassal to an heroic duty, to an intelligence whose eyes are persistently fixed on the future?

The ésprit de la ruche, then, is Maeterlinck's term for what his bee sociology cannot represent, the remainder of his phenomentomological Korporation, the point where he begins to lose the power of his eyesight:

It comes to pass with the bees as with most of the things in this world; we remark some few of their habits; we say they do this, they work in such and such fashion, their queens are born thus, their workers are virgin, they swarm at a certain time. And then we imagine we know them, and ask nothing more. We watch them hasten from flower to flower, we see the constant agitation within the hive; their life seems very simple to us, and bounded, like every life, by the instinctive cares of reproduction and nourishment. But let the eye draw near, and endeavour to see; and at once the least phenomenon of all becomes overpoweringly complex; we are confronted by the enigma of intellect, of destiny, will, aim, means, causes; the incomprehensible organisation of the most insignificant act of life.

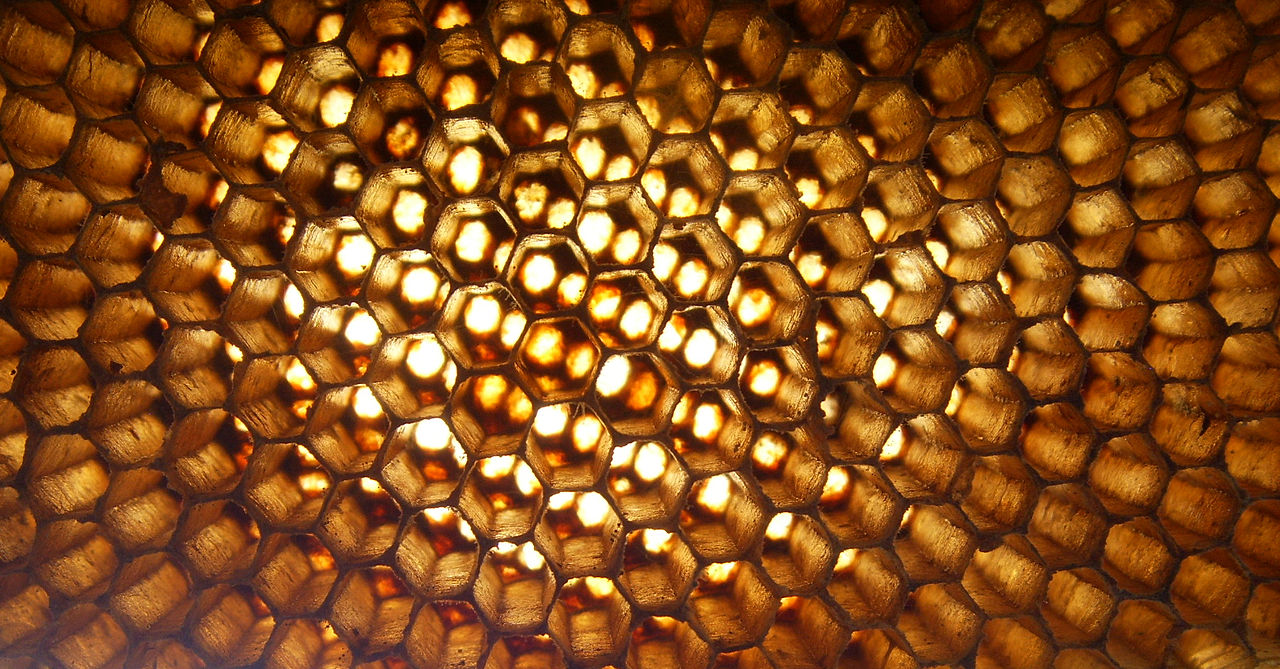

Beneath a waxy layer of faits sociaux, la ruche with its thousands and thousands of cells, its honey, and the silent absoluteness of the ésprit de la ruche. In the schedule of the apiculturalist, this is the hour of the swarm, visible to her as a resounding, spectacular negation of her gaze, a delicious no she can register, although it is, in the end, addressed to her also:

Our hive, then, is preparing to swarm; making ready for the great immolation to the exacting gods of the race. In obedience to the order of the spirit — an order that to us may well seem incomprehensible, for it is entirely opposed to all our own instincts and feelings — 60,000 or 70,000 bees out of the 80,000 or 90,000 that form the whole population, will abandon the maternal city at the prescribed hour. They will not leave at a moment of despair; or desert, with sudden and wild resolve, a home laid waste by famine, disease, or war. No, the exile has long been planned, and the favourable hour patiently awaited. Were the hive poor, had it suffered from pillage or storm, had misfortune befallen the royal family, the bees would not forsake it. They leave it only when it has attained the apogee of its prosperity; at a time when, after the arduous labours of the spring, the immense palace of wax has its 120,000 well-arranged cells overflowing with new honey, and with the many-coloured flour, known as "bees' bread," on which nymphs and larvae are fed. Never is the hive more beautiful than on the eve of its heroic renouncement, in its unrivalled hour of fullest abundance and joy; serene for all its apparent excitement and feverishness. Let us endeavour to picture it to ourselves, not as it appears to the bees, — for we cannot tell in what magical, formidable fashion things may be reflected in the 6,000 or 7,000 facets of their lateral eyes and the triple cyclopean eye on their brow[.]

Let us endeavour, Maeterlinck writes, let us endeavour to picture it to ourselves "as it would seem to us, were we of their stature [but not bees with their eyes]" – a problem of scale; impossible, further, to disentangle this qualitative problem (interpretative silence) from the quantitative; what if sheer mass makes sense stop – and changes into an almost fantastical mode:

From the height of a dome more colossal than that of St. Peter's at Rome waxen walls descend to the ground, balanced in the void and the darkness; gigantic and manifold, vertical and parallel geometric constructions, to which, for relative precision, audacity, and vastness, no human structure is comparable. Each of these walls, whose substance still is immaculate and fragrant, of virginal, silvery freshness, contains thousands of cells, that are stored with provisions sufficient to feed the whole people for several weeks. Here, lodged in transparent cells, are the pollens, love-ferment of every flower of spring, making brilliant splashes of red and yellow, of black and mauve. Close by, in twenty thousand reservoirs, sealed with a seal that shall only be broken on days of supreme distress, the honey of April is stored, most limpid and perfumed of all, wrapped round with long and magnificent embroidery of gold, whose borders hang stiff and rigid. Still lower the honey of May matures, in great open vats, by whose side watchful cohorts maintain an incessant current of air. In the centre, and far from the light whose diamond rays steal in through the only opening, in the warmest part of the hive, there stands the abode of the future; here does it sleep, and wake. For this is the royal domain of the brood-cells, set apart for the queen and her acolytes; about 10,000 cells wherein the eggs repose, 15,000 or 16,000 chambers tenanted by larvae, 40,000 dwellings inhabited by white nymphs to whom thousands of nurses minister. And finally, in the holy of holies of these parts are the three, four, six, or twelve sealed palaces, vast in size compared with the others, where the adolescent princesses lie who await their hour, wrapped in a kind of shroud, all of them motionless and pale, and fed in the darkness. On the day, then, that the Spirit of the Hive has ordained, a certain part of the population will go forth, selected in accordance with sure and immovable laws, and make way for hopes that as yet are formless.

And of course, scale and readability is not to be separated from frequency:

Certain as it may seem that the bees communicate with each other, we know not whether this be done in human fashion. It is possible even that their own refrain may be inaudible to them: the murmur that comes to us heavily laden with perfume of honey, the ecstatic whisper of fairest summer days that the bee-keeper loves so well, the festival song of labour that rises and falls around the hive in the crystal of the hour, and might almost be the chant of the eager flowers, hymn of their gladness and echo of their soft fragrance, the voice of the white carnations, the marjoram, and the thyme. They have, however, a whole gamut of sounds that we can distinguish, ranging from profound delight to menace, distress, and anger; they have the ode of the queen, the song of abundance, the psalms of grief, and, lastly, the long and mysterious war-cries the adolescent princesses send forth during the combats and massacres that precede the nuptial flight. May this be a fortuitous music that fails to attain their inward silence? In any event they seem not the least disturbed at the noises we make near the hive; but they regard these perhaps as not of their world, and possessed of no interest for them. It is possible that we on our side hear only a fractional part of the sounds that the bees produce, and that they have many harmonies to which our ears are not attuned. We soon shall see with what startling rapidity they are able to understand each other, and adopt concerted measures[.]

While the swarm is not fully silent, it could nevertheless hold an inaudible remainder ("It is possible that we on our side hear only a fractional part of the sounds that the bees produce") – and the real silence is that the swarm does not tell us whether it does or not. And while it is not fully deaf ("We soon shall see with what startling rapidity they are able to understand each other"), it might be deaf to what humans do ("they seem not the least disturbed at the noises we make near the hive"), and maybe to parts of what they themselves do ("It is possible even that their own refrain may be inaudible to them").

Concerted measures, almost-audible.

L'ésprit de la ruche, then, is the figure for the impossibility to decide, for the limits of a judgment. It is possible that we hear only a fractional part of the sounds that the bees produce, it is possible that Fernando is counter-plagiarizing Maeterlinck to punish him. It is possible that the refugee is Teresa's lover, it is possible that Frankenstein works a metaphor for Franco's regime; all of this is possible because El espíritu de la colmena follows itself, follows l'ésprit de la ruche: an impossibility to determine which interpretation (of a limited set) ultimately wins over the others, which one grasps the aspects of the Bildraum as they are in 'reality' and not only virtually.

But this does not mean that 'anything is possible', 'anything is true'. It is not because the film is 'woven too loosely', so that 'everything could be true', that the judgment between the interpretations remains suspended. Rather, its inner organization seems so strict that any gesture of interpretation will at some point fall short in front of the opaque gold it is confronted with. It is by virtue of its extreme density of laws that the beehive renders these laws hard to read (and bring forth the spirit of the hive as a phenomenological note of caution – as make-do-method of holding something together that holds together so well that it might as well be incomprehensible).

The dense inner organization of the film can mean that if, for example, we accept the first part of Isabel's theorem, namely that en el cine, todo es mentira, and that thus, the monster from Frankenstein is not real and the monster at the end of El espíritu de la colmena is not real either, but a hallucination on Ana's part, and that El espíritu de la colmena is therefore a coming-of-age story entailing, as part of its internal Bildung, the realization of the monster's irreality (vs. the reality of fascist violence, for example, the darkness of 'adult worlds'), we would at the same time be forced to concede that the meseta depicted and the year signified with "hacia 1940" are mentira too, and thus exactly as real, namely fake, as the monster from Frankenstein, thus meaning that either, the film is not about fascist Spain, or that the monster at the end is actually real in just the sense that fascist Spain depicted in the film is. It is following any rule that leads us out of sense and towards a golden opaqueness.

Making a hermeneutic beeline for content, here, means taking a hexagonal route.

In his Der Sürrealismus. Die letzte Momentaufnahme der europäischen Intelligenz, Walter Benjamin claims the following:

Jede ernsthafte Ergründung der okkulten, sürrealistischen, phantasmagorischen Gaben und Phänomene hat eine dialektische Verschränkung zur Voraussetzung, die ein romantischer Kopf sich niemals aneignen wird. Es bringt uns nämlich nicht weiter, die rätselhafte Seite am Rätselhaften pathetisch oder fanatisch zu unterstreichen; vielmehr durchdringen wir das Geheimnis nur in dem Grade, als wir es im Alltäglichen wiederfinden, kraft einer dialektischen Optik, die das Alltägliche als undurchdringlich, das Undurchdringliche als alltäglich erkennt.

Any serious exploration of occult, surrealistic, phantasmagoric gifts and phenomena presupposes a dialectical intertwinement to which a romantic turn of mind is impervious. For histrionic or fanatical stress on the mysterious side of the mysterious takes us no further; we penetrate the mystery only to the degree that we recognize it in the everyday world, by virtue of a dialectical optic that perceives the everyday as impenetrable, the impenetrable as everyday.

In Benjamin's argument, thus, we penetrate the mystery only to the degree that we find it in the everyday world, and we find it in the everyday world only to the degree that we realize that it is impenetrable (unreadable, deaf, silent, opaque: what if there is only rabble?).

So let me bear this notion of an impenetrable everyday in mind when coming back to that particular, immensely beautiful golden hue of the indoor scenes (in the sentences just after those quoted, Benjamin goes on to speak of Erleuchtung, illumination).

I have already said that because of the honey touch of this light, and because the hexagonal structures of the windows – origin, as filter, of the light – obviously resemble the wax cells of a honeycomb (as if every window were a comb), it has always been tempting to read the beehive as the analogon to the life of this family, or maybe to life in post-Civil War Spain altogether, governed by an incomprehensible, alien, absently reigning force in the shape of El espíritu. So it looks like the honeycomb windows and the honey-light illumination of the rooms favors this rather straightforward kind of allegorical reading after all and gives one interpretation weight over all others (we win an interpretation by following this the-house-is-an-analogon-to-the-beehive-route; we lose nothing except the reality of the monster, which is just another part of an allegorical level: the film's 'punchline', as it were, lies in this lighting, which is allegorical).

But remember what Stanley Cavell said about colour in film:

It is not merely that film colors were not accurate transcriptions of natural colors, nor that the stories shot in color were explicitly unrealistic. It was that film color masked the black and white axis of brilliance, and the drama of characters and contexts supported by it, along which our comprehensibility of personality and event were secured. [...] Movies in color cede our recently natural (dramatic) grasp of those figures, not by denying so much as by neutralizing our connection with the world so filmed.

Cavell's point is that colour in film marks the end of a certain dualism (black and white) in favour of a much more unstable system of hues and degrees; and that the abandonment of this dualism in favour of a suspended judgment (is this colour a symbol of black or of white?) rendered stories "unrealistic" even where they were not explicitly so; their purchase on realism, one could say, was diminished when they switched from B&W to colour – which led, among other things, to an increase in narratologically 'unrealistic' plots, but this was more or less a byproduct of a more fundamental development away from Realism – an estate founded on a dualism realistic/unrealistic transmutable into others (plausible/implausible, white/black, real/irreal, true/untrue) towards colour and its hues.

By 1973, at the time Erice and his team shoot El espíritu de la colmena, colour in film is well established (whereas Cavell is concerned with film at the historical B&W/colour-threshold). Film's abandonment of Realism in its discovery of colour – en el cine, todo se ha convertido en mentira – has been refamiliarized. What the unmissable golden tint (defended by Cuadrado against Erice's wish to film in black & white) of El espíritu does, then, is at least to de-familiarize colour, to re-activate a dynamic it once had: It renders the events depicted 'in it' opaque, precisely not readable as 'metaphors for bees and vice versa'; inhabiting a world to which our connection is "neutralized", in Cavell's words. It is in this fashion, though, that it meets exactly the function of l'ésprit de la ruche in Maeterlinck, which, again, did not serve as an analogous basis on which to make parallels between bees and humans (as Michelet, in L'insecte, entertains), but as an emblem of opaqueness, as the limit of an understanding. Our "comprehensibility of personality and event" is shattered by colour, in this case a honey-gold colour tint, just as Maeterlinck realizes that his "natural (dramatic) grasp" (still Cavell) of apian activity must cede at precisely the point where l'ésprit starts, because l'ésprit is precisely the name for this ceding.

Il arrive, en effet, que plusieurs jours de suite l'émoi doré et transparent s'élève et s'apaise sans raison apparente.

It happens, actually, that for several days in a row, a golden and translucent commotion will rise and vanish without apparent reason.

(Maeterlinck again).

For a double reason, then, Cuadrado's gold is not akin to Hollywood's south-of-the-border yellow. First, and more importantly, it does not increase readability ("We're in Mexico!"). Second, it is not 'fixed in post', but diegetically anchored (the house's windows are painted yellow; outside of the house, the golden hue is absent), which leaves a reading of the film as "so realistic that it is almost documentary" intact, and pushes the whimsical notion of "natural colour" to its most beautifully precarious degree. In a dialectical movement that might please Benjamin, it is natural light, here, that ends Realism's gaslight; it is precisely natural colour that suspends all degrees of 'realism' in this Bildraum, that revives the mysterious by rendering the everyday (of which it is a part, it is no intradiegetic miracle) impenetrable. Is the Realism switch on or off? How to tell, when everything is bathed in honey? When everybody is every body, and every body is torn apart and put together not in trivial -tomy, but in the anatomy lesson of colour and its hues?

Überall, wo ein Handeln selber das Bild aus sich herausstellt und ist, in sich hineinreißt und frißt, wo die Nähe sich selbst aus den Augen sieht, tut dieser gesuchte Bildraum sich auf, die Welt allseitiger und integraler Aktualität, in der die »gute Stube« ausfällt, der Raum mit einem Wort, in welchem der politische Materialismus und die physische Kreatur den inneren Menschen, die Psyche, das Individuum oder was sonst wir ihnen vorwerfen wollen, nach dialektischer Gerechtigkeit, so daß kein Glied ihm unzerrissen bleibt, miteinander teilen. Dennoch aber - ja gerade nach solch dialektischer Vernichtung - wird dieser Raum noch Bildraum, und konkreter: Leibraum sein. (Benjamin, Der Sürrealismus)

Thus, the honeycomb-world of the family house may lead to the beehive and its spirit, yes, but to that spirit precisely as what it is in Maeterlinck (and what it isn't in interpretations that all too easily identify it as an allegorical level to fascist Spain): as impenentrability; as the point where hermeneutic reading reaches its limit and fades to colour. That haunting honey hue is not the promise of allegory, but an instance of the same power that makes the realism of Frankenstein's monster exactly as debatable as the reality of Fernando, of bees, or of Spain.

Cuadrado's gold thus helps to keep Realism deactivated, and as long as Realism is not yet activated, we’re not simply elsewhere. We’re just below Realism, or right outside its door. Or rather, we’re just below genre, outside the door of Realism, but also of the door of Surrealism, the door of Fantasy, the door of Sci-Fi. Rondamos las habitaciones. We stalk around the estates.

WELL BUT THEN ISN'T THIS MAGICAL REALISM, some friend might begin to shout at this point. Haven't we had this back in History of Literature 101? Coexistence of the magical and the real? The mysterious as mundane, failing laundry machines next to virgins transforming into a swarm of butterflies? Neither high fantasy nor straightforward realism? Coming home at 1pm with a coke and a McDo menu only to encounter a fairy, wondering whether that's still the weed talking or whether that's really a fairy; or whether 'fairy', here, is a slur for a male-performing homosexual, say, Lorca? Isn't magical realism precisely when you let that sort of decision be in suspension? Isn't Walter Benjamin's "das Alltägliche als undurchdringlich" simply Alejo Carpentier's real maravilloso (put forth in his El reino de este mundo of 1949... just how large is the scope of that "hacia 1940"), or even Franz Roh's even earlier "magischer Realismus" from 1925?

Kind of, I would answer. It depends. In fact, everything, I think, turns around the hinge of Benjamins das Alltägliche (the everyday). It is the everyday, not 'the real', it is not Carpentier's real, and certainly not 'the realistic'. The 'realistic' is something on which Realism's estate has a purchase, the proof of which is that it is all too easily translatable into other terms: the domestic, the private, the Western, the white, the male, the ethically normal (with all the fascism this term entails). It is quite quickly synonymous to the politically plausible. Not even 'the real', das Wirkliche, appears in Benjamin's text, because he knows what he's doing.

And das Alltägliche, on the other hand, is simply, and no, you won't be surprised: a frequency. Not at all excluding the realistic, certainly not excluding Carpentier's more complex real, it entails simply, but fully, the repeatable and repeated. Das Alltägliche, the quotidian, is moveable: to a soldier in a 1915 trench, it includes shells and gassings, waitings and being-frightened – but from day to day to day [to the last syllable of recorded time, potentially]. To a bourgeois Prussian landowner of 1890, it includes eating, sleeping, and not realizing that your wife is banging someone else. To the wife, it includes reading, sleeping, and banging the gardener's wife. To the gardener's wife, it includes eating, banging her husband's boss's wife, and mixing potions...

Anyway, what counts is that the Alltägliche is at least also an effect of repetition, not of some originary ethical ground. "[W]e penetrate the mystery only to the degree that we recognize it in the everyday world" therefore means, when taken in its full dialectical thrust, that the mysterious is exactly as real as the everyday if it is recognizable in the everyday world, that is: if it is as repeatable and repeated as the everyday world is.

This puts a limit to "WELL BUT THEN ISN'T THIS MAGICAL REALISM".

Because the point about the monster at the end of El espíritu de la colmena is also that this isn't the first time that monster appears, not at all: we've seen it once in the same movie (onscreen in the town hall) but also in another movie called Frankenstein that happens to exist outside of El espíritu de la colmena, too; and then that film is itself an adaptation (and quite a free-spirited one, one must say) of Mary Shelley's novel: so the monster from Frankenstein, when it appears at the end of El espíritu de la colmena, appears not at all for the first time or as something 'genuine' – recall Fernando maybe-quoting, maybe-plagiarizing, maybe-rewriting Maeterlinck – but as something repeated, something shared to the such an extent that we no longer know whether 'Frankenstein' is the monster or the scientist, something that appears in a realm of desire, in an ámbito, that is the effect of a collective desire, of which Ana is but an organ.

And if we want to know how ‘real’ something is, Lorca seems to say, the crucial difference is not between “a fantastic beast” and “a physical thing”, but between “something that is repeatable and repeated across time” (like Frankenstein's monster, a cliché, a myth, un dulce, or a political structure; those are very real) and “something that exists only once” (like the Basílica de la Sagrada Família, or Un Chien Andalou; those are not very real). There are fantastic beasts repeated and shared (such as el coco, or Frankenstein's monster) – those exist; and there are fantastic beasts barely (or not at all) repeated and shared (such as, say, Nagini) – those do not exist, which is to say the exist about as little as the Sagrada Família.

And the 'problem' or the difficulty of magical realism for what I'm saying here is that magical realism doesn't really give a lot of weight to frequencies, which considers individual fantasies (a colonel's daughter is, with her full consent, 'abducted' by a swarm of eight-winged flamingos made of fire) and collective fantasies (a puritan settler family's oldest daughter is seduced by the devil and turns into a witch) on an equal level, although only the second is alltäglich, because repeatable and, for better or worse, repeated (unless eight-winged flamingos made of fire are a collective fantasy).

These different qualifications of frequency have an important impact on the question of realism. For if frequency does not matter, one can easily remain within realism all while allowing for an extraordinary event, which will be relegated to various explicatory modes of 'flights of fancy', which, in the end, only help to reinforce Realism's estate (whether ghost's don't exist at all or only exist in the minds of its inhabitants: in both cases, it will remain unhaunted). On a political level, this can be shown quite simply in the fact that although the genre of magical realism has been popularized by a lot of writers considered 'left wing', say Isabel Allende or Gabriel García Márquez, – and theoretically supported by the aforementioned, at least equally 'left-wing' Alejo Carpentier or Miguel Ángel Asturias – it allowed pretty easily for a Liberalist-individualist appropriation by someone like Mario Vargas Llosa. Non-repeatable and non-repeated dreams sit easy with something that is simply, once again, at home at Realism's estate, and magical realism might still accomodate them. Márquez, probably suspecting what was up, went to a great effort to situate his magic realist masterpiece in the isolated town of Macondo: its isolation, about which he famously made a whole fuzz, one hundred years and what not, was crucial, if the project of magical realism was to be saved: only this isolation could defend the possibility that women transforming into butterflies while hanging up their laundry would be expressions of a collective fantasy (a fantasy that just never left Macondo – but how could it have, with Macondo abandoned and lonely in its century of solitude?) and not figments of just the kind of individual imaginative burp that might as well suit Llosa's rather limited ambitions.

So what I pursue here – the notion of a text just outside realism, allowing for a suspension of judgment about the reality of its aspects – is not simply a difficult circumlocution to arrive back at magical realism. Rather, magical realism probably includes the kind of text I'm interested in, but is not simply coincident with it. Repeatability, rather, is what is at stake: frequency, and for what it matters, the refrain of which both Lorca's study on lullabies and Maeterlinck's study on bees speak ("It is possible even that their own refrain may be inaudible to them").

What is Ana writing? What degree of reality would the events of her texts have?

(This, actually, is what I would consider the true question of this film).

Can we allow for the pun that what she's writing is probably not circling around metaphor (μεταφορά, "carrying over") but anaphor (αναφορά, "repetition")?

And why would this matter? Well,

well,

because Ana, too, might be re-writing, re-writing texts and quotes such as those that claim that

[i]t was for a long time believed that when these wise bees, generally so prudent, so far-sighted and economical, abandoned the treasures of their kingdom and flung themselves upon the uncertainties of life, they were yielding to a kind of irresistible folly, a mechanical impulse, a law of the species, a decree of nature, or to the force that for all creatures lies hidden in the revolution of time. It is our habit, in the case of the bees no less than our own, to regard as fatality all that we do not as yet understand. But now that the hive has surrendered two or three of its material secrets, we have discovered that this exodus is neither instinctive nor inevitable. It is not a blind emigration, but apparently the well-considered sacrifice of the present generation in favour of the generation to come.

Auch das Kollektivum ist leibhaft:. Und die Physis, die sich in der Technik ihm organisiert, ist nach ihrer ganzen politischen und sachlichen Wirklichkeit nur in jenem Bildraume zu erzeugen, in welchem die profane Erleuchtung uns heimisch macht. Erst wenn in ihr sich Leib und Bildraum so tief durchdringen, daß alle revolutionäre Spannung leibliche kollektive Innervation, alle leiblichen Innervationen des Kollektivs revolutionäre Entladung werden, hat die Wirklichkeit so sehr sich selbst übertroffen, wie das kommunistische Manifest es fordert. Für den Augenblick sind die Sürrealisten die einzigen, die seine heutige Order begriffen haben. Sie geben ihr Mienenspiel in Tausch gegen das Zifferblatt eines Weckers, der jede Minute sechzig Sekunden lang anschlägt.