Clipped Essaym V: Mise en Abeille

Den Pessimismus organisieren heißt nämlich nichts anderes als die moralische Metapher aus der Politik herausbefördern und im Raum des politischen Handelns den hundertprozentigen Bildraum entdecken.

– Walter Benjamin, Der Sürrealismus. Die letzte Momentaufnahme der europäischen Intelligenz (1929)

Picture Goya, strolling through a barren Spanish landscape at dusk, kind of like an old man who’s a bit lonely and a bit hard of hearing, and tracing, in slow steps, the almost lunar emptiness around him, the sparse vegetation, the ocean of dust, the vast milkily overcast sky, the few dark and gaunt trees, the furrows segmenting an unhospitable earth –

– and then take Goya out of the image: And you would arrive on something similar to the "lugar de la meseta castellana" where Victor Erice's 1973 film El espíritu de la colmena is set.

The time is "hacia 1940", 'around 1940'; thus, four years after Federico García Lorca's death, in a place of similar rurality, at the hands of fascist militia, and – depending on how much scope we grant that "hacia" – right towards the end or shortly after the end of the Spanish Civil War.

With its rather small cast, the film follows a family of four, plus their maid, living in a somewhat run-down manor in a rural village of central Spain. The family consists of Teresa, the mother, Fernando, the father, Isabel, the older daughter, and Ana, the younger (although there are not too many years separating the two children). Isabel is just a bit older, and tries to use that tiny gap to her advantage within the power dynamic of the two sisters – but am I getting ahead of myself? Maybe.

Instead, fragments of a family portrait – that is, a denied family portrait, fragmenting into portraits of the family members (certainly not the same thing).

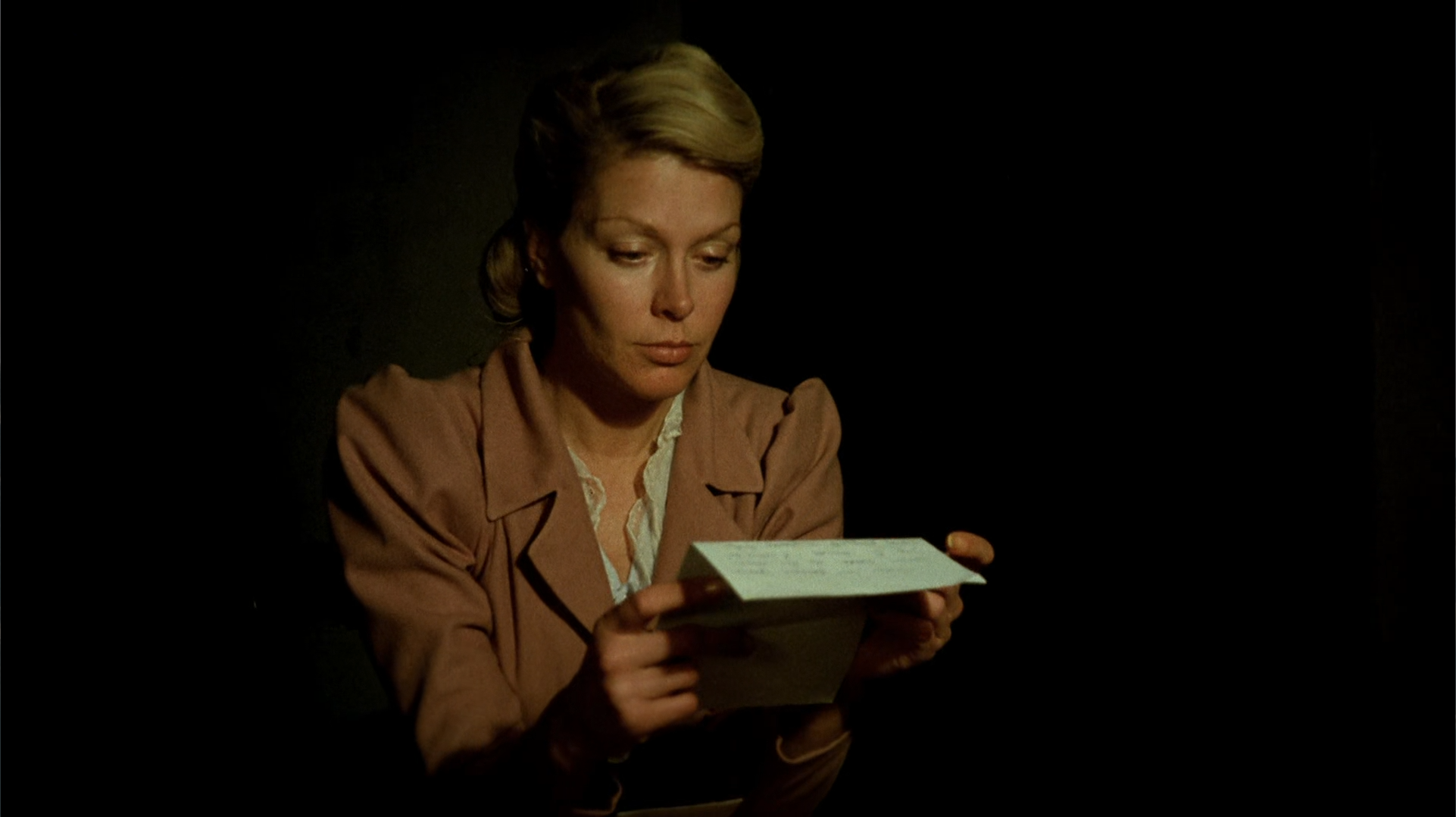

Why not begin with Teresa, the mother: brimming with melancholy. Writes letters to an absent lover and sends them, by train, towards their destination. We know little about their relationship, only – and only from her letter – that the lover has seen the house the family lives in, but when it was in a better state, and has known the landscape the house is set in, but when it was in a less sad and destroyed condition. We know of two letters she writes. We know of almost nothing more.

But what we do know, already, is that what we're dealing with here is an ámbito, a region drawn by a desire.

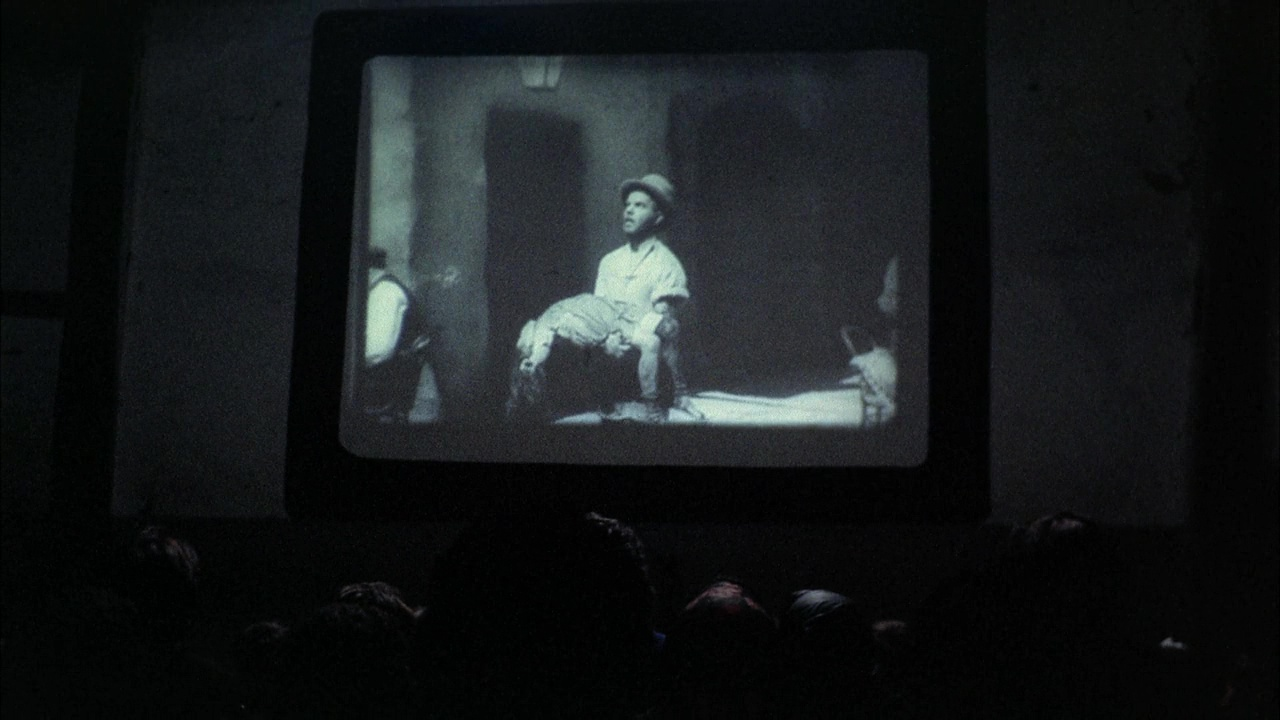

Or why not begin with the first scene of the film, in which a travelling cinema brings a film to the town's hall: James Whale's legendary Frankenstein of 1931. At 5pm precisely, the screening begins, and the two daughters attend, transfixed by what unfolds, in black and white, before them.

This is not necessarily the postmodernist pathos of 'the advent of cinema' (even though an intercut scene showing a steam railroad arriving at the town's station all but quotes the Lumière brothers); but it is the arrival of what Walter Benjamin, in his essays on surrealism, might have called a Bildraum, an image-space. A hall of anorganic life into which a wish can be introduced, or an enigma interwoven, and kept alive.

Ana, the younger daughter, is especially captivated by the scene in which the monster encounters a young girl at a lake:

Now, the film – El espíritu de la colmena, I mean – shows the town people watching this scene, and then cuts back to Frankenstein only after the next scene has already begun, in which a distraught father carries his drowned child into town:

The 'omission' of what happens inbetween is crucial. In full, the scene depicts the monster happily meeting the young girl and playfully throwing flowers onto the lake surface, watching them float on the water. Once there are no more flowers, the monster throws the little girl, thinking that it would float just like the flowers. We then see the monster stumbling away from the lake, visibly confused and sad, and only then the film cuts to the father carrying his dead daughter. Depending on the film version, however, the scene by the lake is omitted altogether, or shows only the monster encountering the girl, skips the flower-part, and cuts directly to the monster walking away from the lake (and then to the grieving father), giving a very different impression of what happened. Because of El espíritu's editing, we cannot decide which version the town audience saw.

Whichever it was, Ana is deeply fascinated by the two scenes, and asks her older sister why the monster killed the girl. In the evening, lying in bed, whisperingly, she repeats the question. Her sister tells her that first, the monster is not real and it did not kill the girl, because everything in the movies is fake; and second, that the monster is an espíritu, a spirit; that it is usually incorporeal and has only assumed a body in order to meet the girl; and that she, Isabel, has met the spirit before.

And of course, from that moment on, the espíritu becomes a fixed mark within Ana's outlook on the world, as something that exists, out there, in the barren fields and thin forests, and that turns the world into a web of threads and indices coming from and leading to that mysterious spirit entity. A space of frights and wishes, harboring, somewhere, like an open secret, the enigmatic espíritu.

Another ámbito.

Or why not begin with that strange title, El espíritu de la colmena, which translates to The Spirit of the Beehive? It seems to push us towards the father, Fernando, who keeps bees:

Whether he is a beekeeper by trade, we do not know. The sort of white-collar-professional-dress he usually wears (suit, trenchcoat, hat, umbrella), and the one instance he's called away on an early morning, leaving on a horse-drawn carriage, suggest otherwise. If beekeeping is his pastime, it is one that seems to absorb a great deal of his time, however, and entails several places (the outdoor-hives depicted above, indoor-hives within the family house) as well as several parts of his day (afternoon and evening, at least). With a higher degree of certainty, one could say that honey is not the prime focus of his beekeeping ventures (if we're dealing with a production of honey, here, it is of a hidden, absent, buried, non-honey kind). Rather, he seems intent on studying them in some scholarly fashion, and he 'keeps book' of his beekeeping activities.

The bookkeeping in question, however, is very peculiar. We are only offered one excerpt of it. I will give it to you in full, and directly in English, because as we will see, this is passage is not exactly Spanish anyway:

"Someone to whom I recently showed my glass beehive, with its movement like the main gear wheel of a clock; someone who saw the constant agitation of the honeycomb, the mysterious, maddened commotion of the nurse bees over the nests, the teeming bridges and staircases of wax, the invading spirals of the queen, the endlessly varied and repetitive labours of the swarm, the relentless yet ineffectual toil, the fevered comings and goings, the call to sleep always ignored, undermining the next day’s work, the final repose of death far from a place that tolerates neither sickness nor tombs; someone who observed these things, once the initial astonishment had passed and quickly looked away with an expression of indescribable sadness and horror."

This passage, written down by Fernando in his notebook, is a direct quote from the English (in Fernando's case, Spanish) translation of Maurice Maeterlinck's magnificent treatise La vie des abeilles (The Life of the Bees) from 1901. And indeed, it is Maeterlinck who coined the term l'ésprit de la ruche – the spirit of the hive, el espíritu de la colmena – to describe what he saw as an inexplicable, incomprehensible force structuring apian society; that which governs the swarm, but is either exactly coincident with the sum of every single bee cell (and only that, and impossible to formulate on any lower level, like "leading group of bees", "this or that bee alternatingly", "the queen", "all the workers"), or completely distinct from every single bee, utterly outside of all bee-ness, and all the more alien (there is an apian society, but there are no bees in it).

So what is going on with Fernando and his notebook? We are forced, I suppose, to consider a set of at least the following possibilities:

(1) Fernando is writing a book on bees, uses Maeterlinck's book as a source, and 'the film happens to catch him' at exactly the moment he quotes his source.

(2) Fernando is consciously copying Maeterlinck, plagiarizing him in order to punish, in some way or other, the wealthy Nobel-prize winner for ruthlessly plagiarizing the chronically ill, depressed, financially destitute and virtually powerless Southern African writer Eugène Marais in the 'sequel' to the bee-book, La Vie des Termites – Fernando, then, keeps book not only in a documentary, but especially in a moral, maybe even metaphysical way (as Maeterlinck and Marais might never ever hear anything about the prosecution Fernando is leading, out in some corner of the Iberian meseta).

(3) Fernando is consciously re-writing Maeterlinck's text; in just the way that Pierre Menard, in Borges' Pierre Menard, autor del Quijote, re-writes Don Quiijote, syllable for syllabe, word for word, chapter for chapter. "Su admirable ambición era producir unas páginas que coincidieran palabra por palabra y línea por línea con las de [Maurice Maeterlinck]." Like Menard, Fernando thus produces a text infinitely richer – "infinitamente más rico", Menard's reviewer writes – than its completely identical predecessor; enrichened as the former is by the changes of time (Maeterlinck's "the final repose of death far from a place that tolerates neither sickness nor tombs" is mere fin-de-siècle pathos mixed with a crude anthropomorphism, but Fernando's "the final repose of death far from a place that tolerates neither sickness nor tombs" is a scathing attack on Francoist Spain). [Recall, also, that Menard's other works dealt, in different ways, with Francophone symbolism, of which Maeterlinck was a part.]

(4) Fernando writes what he considers his book on bees and beekeeping and just happens to copy and/or re-write La vie des abeilles word for word, syllable for syllable, línea por línea, fully convinced that he, an individual, writes an individual text, unconscious of the fact that someone else has actually written that very same text: two hands, two feathers, guided by an obscure vanishing third, an else, which governs both on a level beyond their intentionality.

(5) Fernando, and thus, we might at least assume, the rest of the characters, live in a world in which Maeterlinck has either never written La vie des abeilles or has never existed at all; that, thus, Fernando is writing a genuinely original work, is writing lines never written before in the universe he inhabits, because he, like everything else in the movie, exists in a world fully different from our own.

Whichever interpretation one prefers, it is essential that the film itself gives us hardly any reason to favour one over the other; the film's own judgment on this prism of possibilities is suspended: it is just this prism (including maybe more options, which I've overlooked). And it is equally essential that whichever interpretation one chooses, with the exception of (5), they all are 'about' repetition and repeatability. Only the interpretation that seems (to me) the most unlikely – but again, there is nothing in the film that would ever truly render it impossible – namely (5), discards any aspect of repetition.

And whichever interpretation one prefers, it seems to guide you back, inevitably, to Maeterlinck's text and that notion of an ésprit de la ruche, of an enigmatic force governing the swarm's activities, the politics of a given bee state.

Or, we could begin with the film's particular colour scheme. It has become indispensable part of El espíritu de la colmena's mythography to mention that its cinematographer, Luis Cuadrado, was going blind during filming. His farewell to eyesight is marked by an impeccable, haunting golden light: The scenes taking place within the family house are bathed in a tranquil honey luminosity:

This blonde tint, reserved exclusively for indoor-scenes, is not a filmic filter (in the sense of an add-in during production). Like every other scene of the movie, it relies fully on natural light, and the reason for the perpetual golden hour indoors lies in the particular kind of glass used for the windows:

While the director, Victor Erice, had first planned to shoot El espíritu de la colmena in black and white, Cuadrado convinced him otherwise and employed his own father, a glass painter, to meticulously paint every single of those hexagonal glass fragments a mild yellow, leading to those peculiar swaths of golden haze passing through the rooms. The yellow tint is thus artificial, but intradiegetically so; it is not at all akin to the "south-of-the-border-yellow" in which Hollywood films like to drench every scene set in Mexico at least since Traffic. There is a particular hue to the world within the family house's walls, but there is an in-film reason for this hue; its deliciousness and its enigma are part of the filmic world itself, that is of its Bildraum.

Because of the honey touch of this light, and because the hexagonal structures of the windows – origin, as filter, of the light – obviously resemble the wax cells of a honeycomb (as if every window were a comb), it has always been tempting to read the beehive as the analogon to the life of this family, or maybe to life in post-Civil War Spain altogether, governed by an incomprehensible, alien, absently reigning force in the shape of El espíritu. The colmena neither begins nor ends in one (or the sum) of Fernando's hive boxes, but encompasses social life of the whole family, living as they are between the honeycombs, in golden light, following their little schedules, incomprehensible to each other, incomprehensible to us: what is Fernando writing, exactly? To whom is Teresa writing; does the addressee exist somewhere outside her head? Does Isabel believe in the spirit, or is she only pretending she does and tries to make the younger and more naive Ana believe in it, in some game of power? Does Ana believe in the spirit; and is the spirit the same as El espíritu [de la colmena]?

And indeed, separation lingers over the family as if each member were dwelling in their own wax cell: the adults hardly ever share the screen (they do once, but in a scene where Teresa stands on the balcony, and Fernando down on the ground, so with quite some separation between them). Teresa and Ana have one scene with shared screentime; and there is a forest scene where both children share the screen with their father as they all look for mushrooms. There are breakfast scenes, where the family is supposedly assembled around the table, but the film cuts from one to the other without every truly letting the characters share the screen. That they are, in fact, sharing a room within the film at that particular moment, is something we as viewers have to fill in. Ana and Isabel share the screen frequently, but there again, separation creeps in: first, due to a development within the film's narrative that leads Ana to no longer trust her older sister; and second, due to the fact that in what seems one of the two most intimate scenes between the children, where the two are lying in their beds, talking about the film they saw, whisperingly, with Isabel offering up the great secret of the spirit that roams somewhere out there: this scene was filmed with each of the two children separately, with Erice reading the other girl's part, and then edited together to give the impression of a conversation filmed shot/reverse-shot (this is also the scene in which Isabel says that "en el cine todo es mentira", in cinema, everything is a lie). More often that seems to be the case at first sight, then, even the two children are actually separate from each other, each in their wax cell, and cells all the way down.

So, if Fernando is re-writing La vie des abeilles in a project similar to Menard's re-writing of Don Quijote, in order to imbue an identical textual surface with a different production history, he could be doing so in order to shed light on how his family works: as a swarm within a hive, guided by an incomprehensible spirit. Really, whatever is related to frequency seems to confirm this: be it the color frequencies 'let through' by the filtering windows, or be it the acoustic layering within the house. Part of Fernando's evening habits lies in listening to shortwave radio, and one is tempted to say that he listens to the BBC or some other program prohibited in fascist Spain; to a frequency, anyway, that is hard for states to censor (as shortwaves can travel over thousands of miles without the need of an intermediate transmitter, so a single shortwave emitter in London can transfer its messages to a recipient in the meseta without it having to pass through any 'official', state-controlled transmission gate). While he listens to the radio, the two children have their conversation in bed, about the spirit; and because they are supposed to be sleeping, they wisper, choosing, themselves, a hard-to-control frequency. While Isabel explains that the spirit is indeed somewhere out there, Ana overhears the steps of Fernando as he paces through his reading room, listening to the radio, and the heavy steps of the father make it easy for both Ana's and the viewer's (and listener's) imagination to hear the heavy steps of the intermittently corporeal spirit within them –

– as it "ronde las habitaciones", in Lorca's words, 'stalks around the house', all while está el padre en casa, the father is in the house (in his reading room, listening to radio), but now inhabiting the very acoustic frequencies that allow him to collapse, on some level, into el papón, the big-daddy-of-control that is the Castilian version of el coco.

Papa's boots. Recall, here, that the shape the spirit has taken in the one instance is the monster from Frankenstein, a name that cannot but echo, especially when pronounced in the Spanish accent employed by the itinerant showman who presents it in the town hall, that other, Big-Daddy-of-Control name: Francisco Franco. What exactly is your job, Fernando? What kind of radio are you listening to? What did you do in those previous years, before you entered the fog of "hacia 1940"? Are you a melancholy, desperate dissident exiled in a nowhere, defending a golden light for your family, keeping bees, taking revenge for Eugène Marais, quietly criticizing fascism by re-writing La vie des abeilles, holding hopes up, listening to the BBC? Or are you another syllable of the disturbingly stupid refrains of el papón, of Francisco "Frankenstein" Franco and his Colonel[s] Coco, that are somewhere out there? Why is your wife so distant from you?

But note that these are question marks, and must remain as such for the moment. Again, we're confronted with a prism of possibilities, with the film suspending its own judgment.

Let me instead follow Ana's thread, as it were, and go to the other scene in which she discusses the spirit. This time, it is with her mother, in the one scene they share screentime. Teresa combs Ana's hair, and while she does, Ana asks her what a spirit is.

Un espíritu es un espíritu, Teresa replies. A spirit is a spirit [and nothing more, she implies: don't come at me with metaphor]. Are they good or bad, Ana wants to know. To good girls they're very good, the mother answers, to bad girls they're very bad.

So abstract is the blur that is el coco, Lorca says, that the fear it evokes is a cosmic fear, but it is also so abstract that its characteristics will depend almost exclusively on the imagination of the child – y puede, incluso, serle simpatico. One can even grow to like it.

In some proximity to the family house, there is a dusty field with a stone hut and a well; first seen only as what looks like a perforation of the field-tissue, like two holes (and the association with eyes is stressed by the fact that the scene just before is a school scene, an anatomy lesson, during which Ana has to 'install' the eyes of a cardboard human figure).

From up close, it looks like this:

The two children are drawn to this empty, run-d0wn hut and especially to the well because it seems to hold some mystery. It is the house of the spirit, Isabel says.

And it is in this stone hut that, later in the film, an injured refugee, by all signs an anti-fascist partisan fighter, takes shelter – only to be found by Ana, who discovers him by accident as she goes back to the hut.

The film does not tell us about the epistemological reaction Ana has towards this new person: whether she is quick to identify him as the spirit, now in the body of a different-looking, but still tall and somewhat darkish man; or whether she thinks he's 'just' a stranger with no metaphysical upgrades. But it does tell us Ana's ethical reaction: without any visible degree of being scared, maybe in spite of a level of fear, she immediately starts to care for the injured partisan. She brings him food and her father's coat and pocketwatch; in scenes that, in the mixture of the small girl's selfless care and the strangeness and foreignness of the tall man, seem like a refrain of the lake scene in Frankenstein.

And it is in this house that the refugee is, eventually and in the middle of the night, found by the fascist police, and shot on site.

Fernando's pocketwatch is apparently iconic enough (or holds his name engraved) that it is easily traced back to him. He is briefly questioned by police, shown the refugee's body; Fernando shakes his head, no, he doesn't know this person. He's let go without any obvious further inquiry. His 'no' is apparently enough. (What did you do in those previous years, Fernando, before you and your family entered the fog of "hacia 1940"? What exactly is your job now?)

If the discovery of the pocketwatch on the fugitive seems to have no consequence for Fernando, it seems to have some sort of consequence on Teresa and Ana. Let me start with Teresa. It is necessary, here, to go back into her ambito, intimately tied as it is to letter-writing by hand. This is what she writes in the first letter the film tells us about (again, I will give it to you directly in English):

"Though nothing can bring back the happy hours we spent together, I ask God to grant me the joy of seeing you again. That's been my constant prayer ever since we parted during the war and it's still my prayer here, in this remote spot where Fernando, the girls and I try to survive. Except for the walls little is left of the house you once knew. I often wonder what happened to all the things we had there. I don't say it out of nostalgia. It's difficult to feel nostalgic after what we've been through these past few years. But, sometimes, when I look around and see so much loss, so much destruction and so much sadness, something tells me that our ability to live life to the full has vanished along with it. I don't even know if you'll receive this letter. The news we get from the outside world is so scant and confused. Please write soon to let me know you're still alive. With all my love, Teresa."

Everywhere it counts, this is difficult to interpret: what seems clear is that she's writing to someone she once knew (and still loves). But we do not know whether this is a lover, a friend, or a family member. Every sentence would make sense adressed to either of the three possible recipient-types. Apparently, the house the family lives in now (with the honeycomb windows) is not the first house Teresa has lived in. She met the addressee in the house she lived in before, but that house is destroyed or at least damaged beyond livability. It could be, thus, that she is writing to ther brother, and the house in question is, say, the house they grew up together. Or it could be a former lover, a former husband even; or it could be a childhood friend. The degree of secrecy Teresa enshrouds her letter-writing with seems to suggest some aspect of illictness, possibly tilting the balance towards 'lover', but then secrecy and hidden frequencies are so prevalent features of the family house that it should maybe not be valued too highly in this case.

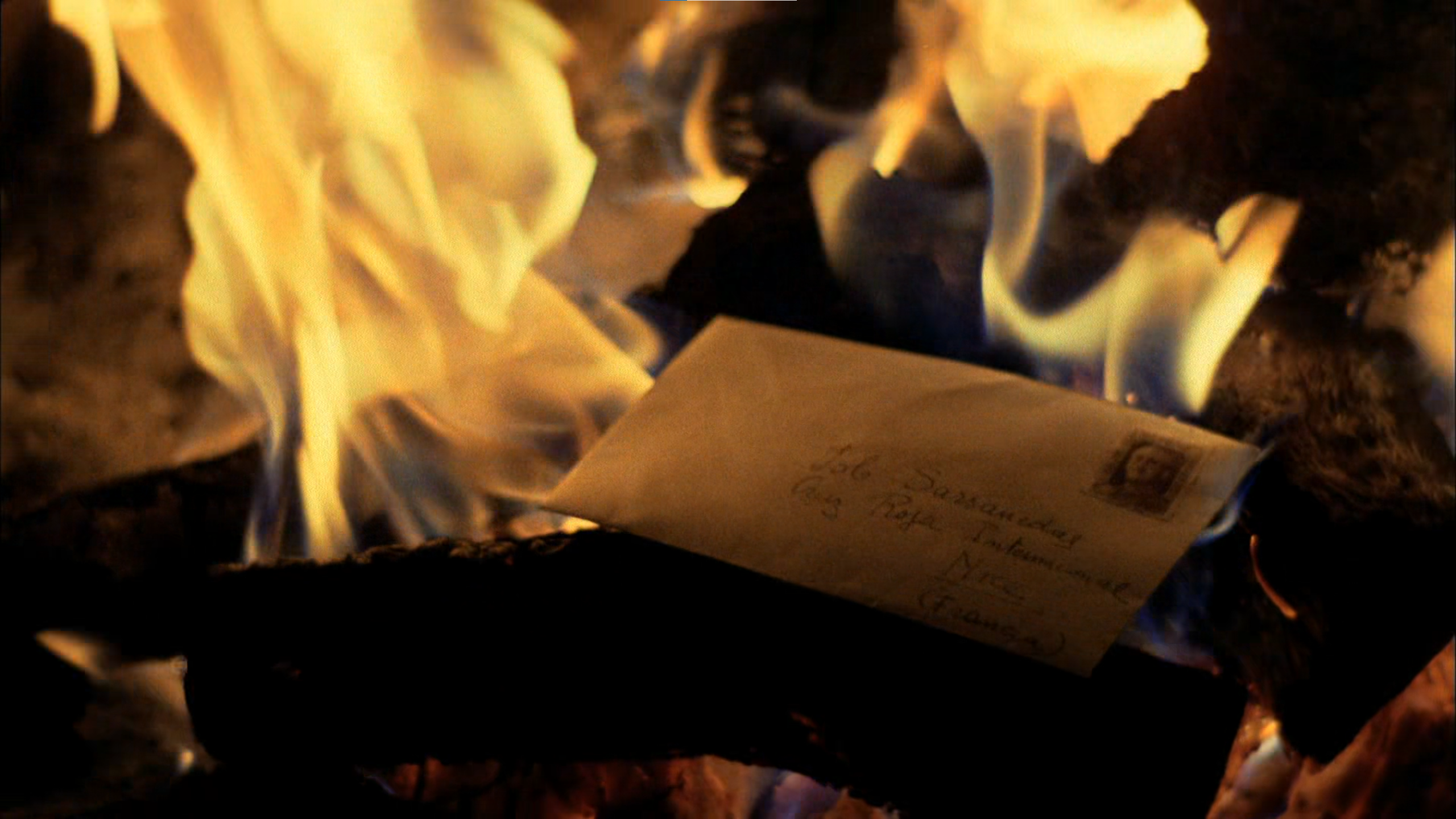

What we further know is that she brings these letters to the train station and sends them off by railway; by the same railway that brings the refugee to this abandoned corner of the earth (he jumps off a train wagon). And what we also know is that, although we do not know what she writes or has written in that letter, she burns one just after news is around that a refugee was shot in the small hut outside town. She neatly folds the letter, puts it into an envelope, and then throws it into the fire.

The advantage of this shot is that it gives us an address, or at least if one could read it it would. What I can make out is this:

Job [?] Sass[?], Cruz Roja Internacional, Nice, (Francia)

So if – and only if – we assume that this is the same address every other letter of hers was sent to, we know that the addressee lives in Nice, France, and has something to do with the International Red Cross. Much like with Fernando's bookkeeping, Teresa's letter-writing and more importantly letter-burning, then, would open up a prism of possibilities, two of which must immediately come to mind:

(1) Teresa was writing to a real person in Nice, France; but she got the news that this person has died, so she doesn't send her last letter but burns it. The problem with this interpretation is that we wouldn't know how she got that information ("The news we get from the outside world is so scant and confused."). Maybe she assumed that not getting a response for so long means that the other person is surely dead.

(2) Teresa was writing to a real person in Nice, France; this person was with the Red Cross because of injuries suffered in the Civil War and in France because he was on the losing (=republican) side, so he had to flee Spain. Maybe because of the Italian fascist attack "hacia 1940" on the Côte d'Azur, he had to escape again and this time chose to flee back to spain, hoping to reach Teresa, but is killed just before reaching his destination.

Or, third: Teresa's letter-writing is closer to a certain interpretation of Fernando's book-keeping in that she her writing engenders a symbolic power. Addressed to a personified 'outside', she keeps a hope up, channels a desire, produces and reserves a Bildraum. She scribbles a speculative name, hardly readable, onto the envelope, and sends it off by the one artery that leads to the outside, the steam railway: "Cruz Roja Internacional" is there as a symbol for collective care not bound by nationalist constraints, and "Nice" is there as an "I love you" or an "Go fuck yourself" kind of nod to her husband, because Nice is where, "hacia 1940", Maeterlinck lives.

This third variant would mean that Ana would be correct if she thought that she encountered the spirit when encountering the refugee, precisely insofar as the refugee is (as much as this verb can mean anything, here) el coco.

As el coco arises as the full textile heap of desire, in fright and arousal, between the child and the mother, as the third of their frequencies.

"Un espíritu es un espíritu" (Teresa), "Después de todo, ese hombre misterioso que está en la puerta y no debe entrar es el hombre que lleva la cara oculta por el gran sombrero, con quien sueña toda mujer verdadera y desligada" (Lorca) – is a spirit bad? – To good girls, he is very, very good.

Abstract enough to not be governed by rules of logic – it appears out of nowhere, of thin air, without reason why it knows where the child and woman are, without reason why it exists but their interaction – it is nevertheless bound to a single rule, formulated in lullabies as much as in Lorca's study of them:

El que está en la puerta / que non entre agora

Nunca puede aparecer aunque ronde las habitaciones

It cannot enter the house, it is out there, maybe just outside of town, but no matter how impossible its journey to arrive there, it will not, never, make the last tiny steps required to join the mother and the child.

El espíritu is el coco, but el coco is precisely not necessarily el papón.

Yes, Francisco Franco is a refrain of "Frankenstein" but as everyone knows, Frankenstein is not the name of the creature, but of the madman doctor, of the father of the child that cries, of Big-Daddy-of-Control: of Papa Doc.

Just like the alternative translation I gave of one of the lullabies discussed in Lorca:

El que está en la puerta

que non entre agora,

que está el padre en casa

del neñu que llora.

Ea, mi neñín, agora non,

ea, mi neñín, que está el papón.

El que está en la puerta

que vuelva mañana.

could be translated to, if only in spirit,

The spirit who is at the door

May not come in now,

For Papa Doc is home,

The father of the child that cries.

Oh, my baby, not now,

Oh, my baby, Papa Doc is here.

May the spirit who is at the door

come back tomorrow.

And as I said back then, this mañana is of a complicated and melancholic temporality (every instance of the lullaby sung reinstates the agora and its non), but it might be a tomorrow indispensable to Teresa – and others. At this point, I have to come back to the family member I've discussed least so far, Isabel, who gives a pretty precise qualification of the monster: It did not kill the girl, and it did not get killed itself, because everything in the movies is fake. And also, she's met the monster before, and it is not a monster, nor a ghost, but a spirit. That is, the movies are fake, but that doesn't mean the monster does not exist. It is, so to speak, untouched by the fakeness of the movie. Its reality does not rely on the veracity of the filmic world in which it is presented. Similarly, lullabies are fake (mother and child are not actually in a stone hut somewhere in the mountains or on a barren field outside town, there is not actually el coco roaming around the house), but that does not mean that there is no coco (nor no papón).

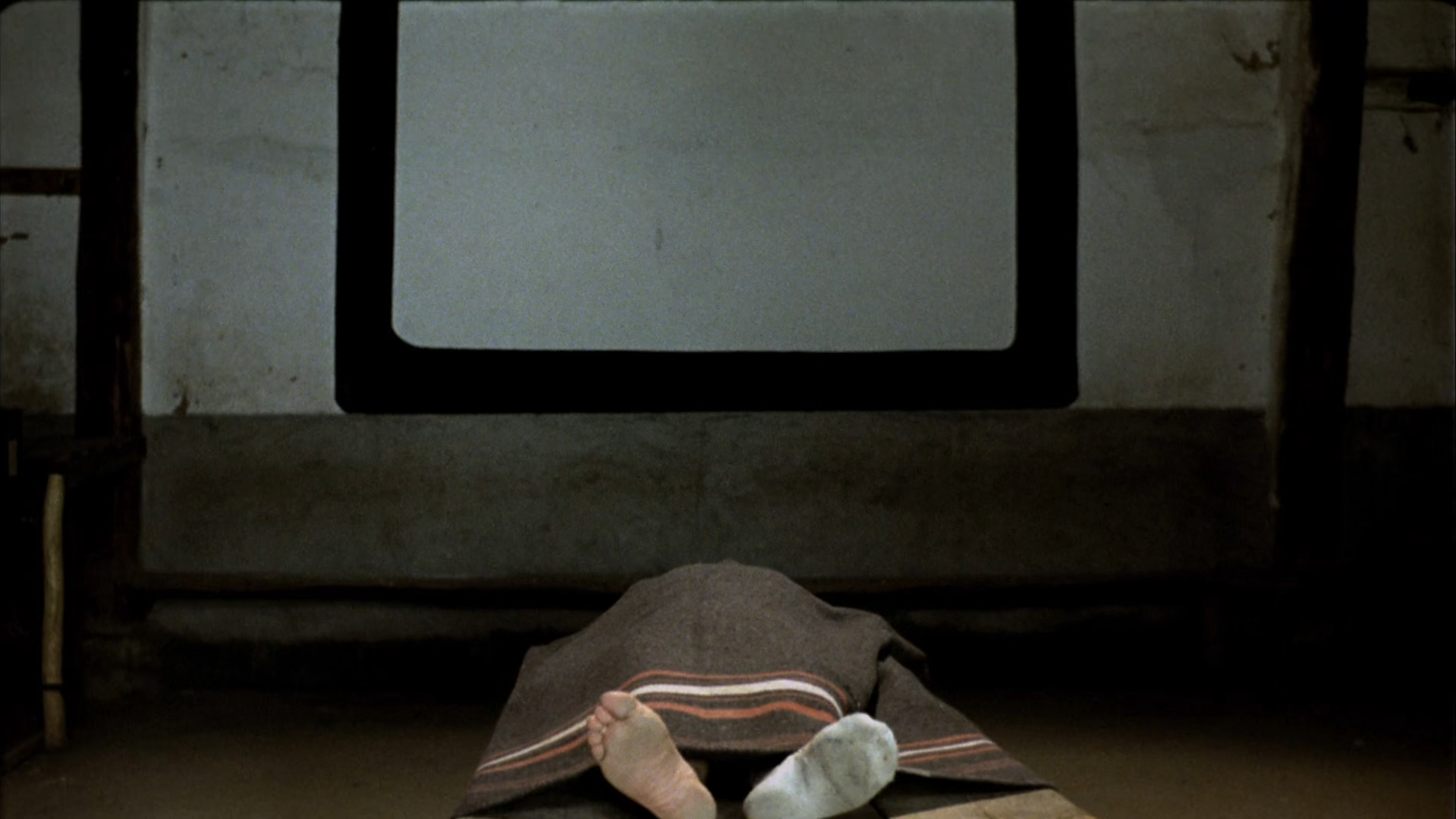

It is only when el coco appears and is killed that it no longer exists, which is why Teresa burns the letter: Writing to something that does not exist yet was possible ("It's difficult to feel nostalgic after what we've been through these past few years"), but writing to something that did not exist and then stopped existing is impossible. To Teresa, this step must feel like disappointment; to Ana, the encountering of the espíritu as no more nor less than that is something that can be framed in a teleologic of 'growing up'. Both must feel the sudden anulment of a considerable libidinal investment. Both must feel that a lot more and a lot less than a human being has died in that little hut. Both have a scene featuring a fire shortly after the refugee's death: in Teresa's case, it's the scene before the fireplace with her burning the letter; in Ana's, it's a scene with her watching other girls jumping through a summer solstice bonfire while standing by the side; both scenes vaguely evoking an ending, Ana's (through the solstice) quite strongly a renewal also. In the absence of both women, a third scene, with Fernando being presented with the dead refugee, unfolds; the refugee happens to lie, dead and covered with a blanket, in the town hall, just under where the screen was during the Frankenstein-screening, now empty and grey – the spirit gone:

Lullaby over.

With not consolation but "the final repose of death far from a place that tolerates neither sickness nor tombs". The beehive, "with its movement like the main gear wheel of a clock" leaves us with nothing than "an expression of indescribable sadness and horror."

But does it? Ana chooses to run away, into the forest, not towards the hut of the spirit/monster/coco, but into the woods. At night, she arrives at a small lake and sits down by its banks:

Silently establishing a refrain to the iconic lake scene she's sceen on the town hall screen.

She watches herself as reflected on the water surface – recall Lorca, here, and his notion that in the lullaby, "La madre adopta una actitud de ángulo sobre el agua al sentirse espiada por el agudo crítico de su voz" and my observation that Lorca's sentence leaves open whether that observing is done by the mirror-image reflected on the water’s surface (which would mean, in accordance to the lullabies wherein the mother-figure adopts the viewpoint of the child, that the “acute critic of voice” is the mother-figure herself as reflected on the surface of the child – she watches her reflection as in a mirror and is thus, in turn, watched by it); or whether that acute critic lies somewhere beneath the surface, beyond the reflected surface image, in the (impenetrable?) depths of the dark waters, and that it could also be that the “most acute critic of voice” is a third character, neither the mother-figure nor the child, but someone alluded to or invented in the interplay of the two first characters. Because what Ana sees, when she looks into the waters, is this:

And it is at this point, I argue, that this film becomes more than merely beautiful, well-made, or interesting, because next we cut back over Ana's shoulder to the forest behind her, and see this:

And it is as if in this moment, the film would lift its hand (or tentacle) and show the realism switch completely untouched. It does not change anything; rather, it shows, out of nowhere, that nothing was changed all along. It is not a scene that bullies itself into the front row as a supposed 'highlight'; rather, it throws into jeopardy any interpretation that would claim one scene as 'more telling' than any other. It is not a plot twist, it just confirms that the plot has been left untwisted from the very beginning on.

It shows that we have not entered the state of the real as realism's real estate: rather, rondamos las habitaciones. We stalk around the houses.

So high-church filmic realism has two options: either discarding this scene as a 'hallucination' or an 'extended metaphor', for which we have little to no ground (at least, it would allow the a-realist school to say that in this case, we could, with comparable evidence, claim that the film takes place in a world where Maeterlinck never was and that Fernando is thus writing a genuinely original work). Or it has to concede that the straightforward, anti-metaphorical appearance of a monster makes the film precisely what it identified as from the very beginning on:

A bee movie.

YOU HAVE RECEIVED

ITEMS (1)

CHARACTER (LVL 1940) 1x EL COCO (CUADRADO VERSION)

TEXTS (1)

MAURICE MAETERLINCK: LA VIE DES ABEILLES