Clipped Essaym IV: Audible Frequencies

For parts I-III, see here, here, and here.

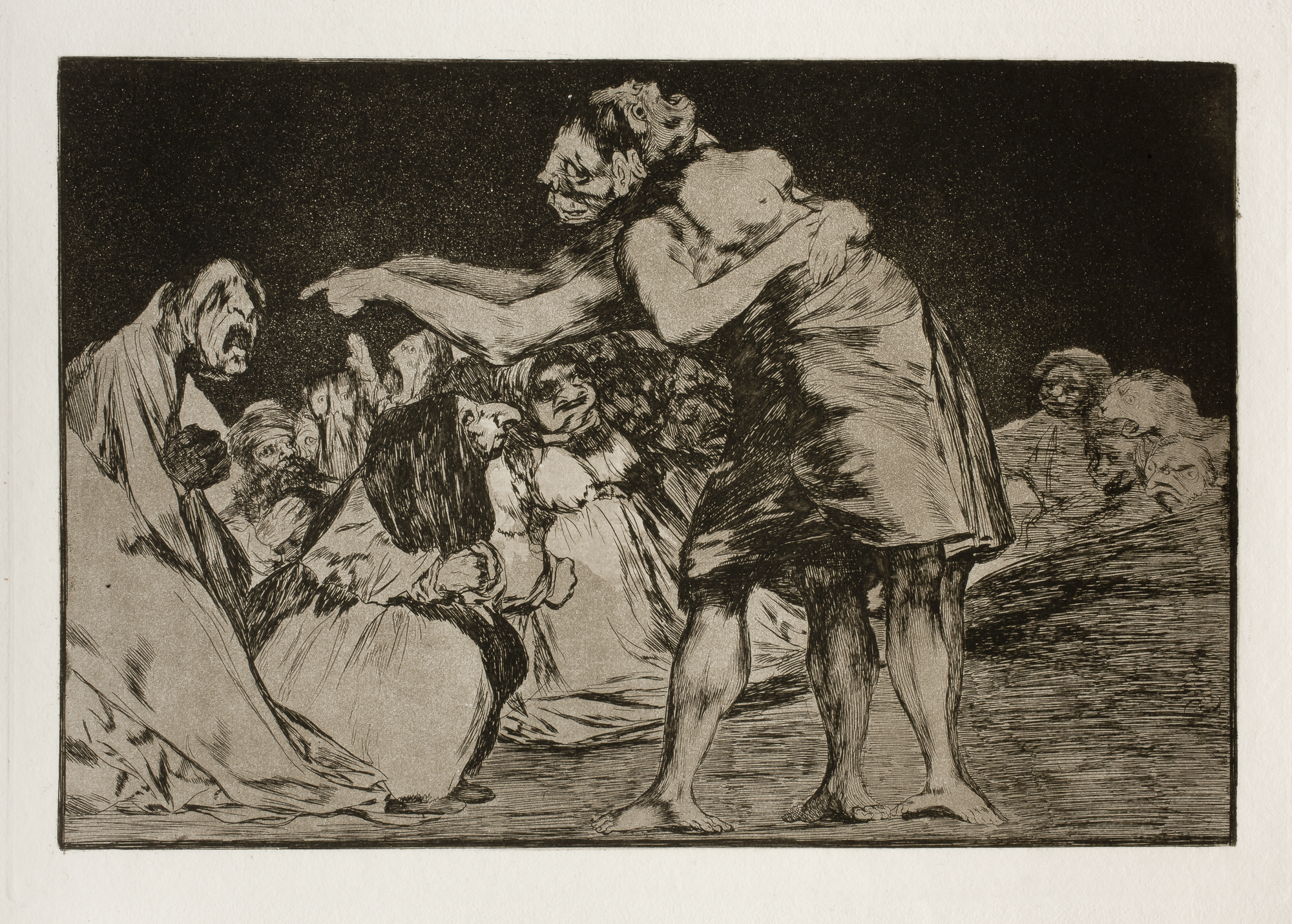

Is it any wonder that early descriptions of modern society have been so prominently haunted by the phenomenon of the rabble? Progenitors of social theory from Michelet and Hegel to Marx and Tarde have been concerned, in various ways, with those who are, in a much later formulation of Rancière’s, ‘the part [of society] that has no part [in society]’ (part sans-part) – with the latently aggressive mass of people who beg and steal, rob and rape; who refuse to work, who indeed refuse to contribute to society tout court but who, nevertheless, ask everything from it; who demand abundance and offer excrement; who one lazily calls the ‘outcasts’ of society; with the vulgar, uneducated, untrained, unclean, brutal, deaf, silent, and stubborn.

For Hegel, Frank Ruda has famously shown that the rabble (Pöbel) functions as a sort of phantom pivot of the Grundlinien der Philosophie des Rechts (1820), a hinge around which the work turns, a central problem it admits it cannot really solve (and towards which it reacts with a mixture of interest and anger). In his attempt to provide a reasonable (vernünftig) description of the workings of modern society, Hegel is quick to identify poverty as a core problem, “bewegend[] und quälend[]”, of modern bourgeois society, insofar as it is a structurally inevitable byproduct of its inner workings – poverty is a “bewegend”, moving, problem of modern society as it is a problem brought forth by the movement of said society itself; impossible to simply be left behind or discarded, and impossible to ‘take back’ through any recourse into past social forms. Tied to the movement of modern society, it is here to stay moving; as the counterpart and byproduct of the existence of “unverhältnismäßiger Reichtümer”, to which it works, within the clockwork of modern society, like a pendulum:

Wenn die bürgerliche Gesellschaft sich in ungehinderter Wirksamkeit befindet, so ist sie innerhalb ihrer selbst in fortschreitender Bevölkerung und Industrie begriffen. – Durch die Verallgemeinerung des Zusammenhangs der Menschen durch ihre Bedürfnisse und der Weisen, die Mittel für diese zu bereiten und herbeizubringen, vermehrt sich die Anhäufung der Reichtümer – denn aus dieser gedoppelten Allgemeinheit wird der größte Gewinn gezogen – auf der einen Seite, wie auf der ändern Seite die Vereinzelung und Beschränktheit der besonderen Arbeit und damit die Abhängigkeit und Not der an diese Arbeit gebundenen Klasse, womit die Unfähigkeit der Empfindung und des Genusses der weiteren Freiheiten und besonders der geistigen Vorteile der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft zusammenhängt.

Das Herabsinken einer großen Masse unter das Maß einer gewissen Subsistenzweise, die sich von selbst als die für ein Mitglied der Gesellschaft notwendige reguliert – und damit zum Verluste des Gefühls des Rechts, der Rechtlichkeit und der Ehre, durch eigene Tätigkeit und Arbeit zu bestehen –, bringt die Erzeugung des Pöbels hervor, die hinwiederum zugleich die größere Leichtigkeit, unverhältnismäßige Reichtümer in wenige Hände zu konzentrieren, mit sich führt.

Crucial, here, is the “Gefühl[] des Rechts, der Rechtlichkeit und der Ehre, durch eigene Tätigkeit und Arbeit zu bestehen” – the rabble is “quälend” to modern society because it refuses to comply with its core principle: that the rights it grants are founded on labor. To be a functioning member of modern society, Hegel argues, is to be a part of its labor economy; in the activity as worker, the human being turns into a civilian, with rights and duties, privileges and conditions. By founding itself on the production of value, however, bourgeois society keeps producing those who produce ‘nothing of value’; it necessarily brings forth those it cannot provide with the means to fulfill their duty. It brings forth the rabble, as a structural necessity.

If Hegel lists a number of instruments with which the emergence of Pöbel can be fought, it is nevertheless clear (certainly clear to the text, if not always clear to Hegel) that they are insufficient: Notrecht (simply allow stealing for subsistence, on the moral grounds that the necessity to survive surpasses the civil duty of respecting property) must remain reserved for exceptional cases and cannot be generalized without breaking the social contract of bourgeois society. If the state allots labor in order to ‘force’ full employment into being, it produces a crisis of surplus production (unless it also allots consumption, which, again, breaks with bourgeois society). Colonialization of other regions (and thus re-calibrating the subsistence market) achieves a mere postponement, as it changes nothing about the structural conflict within bourgeois society but instead only delays rabble-outbreak in what is now a colonial metropolis (that can, temporarily, export conflict into its peripheries). Policing (Polizei) can only represent and defend the bourgeois order, and thus the very system that continually brings the rabble forth. Worse: Polizei tasks itself with defending the bourgeois order, but not on the abstract level on which this order exists, but on a day-to-day basis, in the shape of situations, subject to randomness and relativization. “Es sind die Sitten, der Geist der übrigen Verfassung, der jedesmalige Zustand, die Gefahr des Augenblicks usf., welche die näheren Bestimmungen geben”, Hegel argues – and thus to the individual judgment of policing individuals in the moment, individuals that defend an objective order in a subjective mode (“Alles ist hier persönlich; das subjektive Meinen tritt ein”).

Durch diese Seiten der Zufälligkeit und willkürlichen Persönlichkeit erhält die Polizei etwas Gehässiges.

If nor Notrecht, nor Colonialization, nor Polizei can sufficiently change anything about the bourgeois order, the same goes for Korporationen, Hegel’s notion of what is basically a proto-union: its members would be protected from job loss to a degree, and the capital amassed from the membership fees would go, among other goals, to paying an ersatz-salary to people who lose their job for the time they are between positions. Thus, Korporationen would prevent the emergence of rabble (as being pushed out of the labor market would not mean being also pushed off of all platforms from which a new position within the labor market could be accessed; one can still search for a new job ‘as a functioning member of society’, with the help and support of the “zweite Familie” that is the Korporation, not as an organ of rabble).

Yet Ruda has poignantly formulated the limit – to which Hegel seems oblivious – of the Korporation in its attempt to prevent rabble:

The corporation is able to grant the security of its members. But it knows the poor only as former, capable producers. Or to put it differently: it only feeds and supports the poor that it knows. […] The corporation always knows a remainder and this remainder is the poverty of those that it does not know.

Thus, although the Korporation can prevent impoverishment of a select few, it cannot prevent the existence of the already-impoverished, the already-rabble. In the end, the rabble is characterized by passing no test at all, by having fallen through every net; impossible that rabble would ever be accepted into a Korporation (if it could be, it would not be rabble).

But what Ruda calls the Korporation’s “remainder” leads into the very heart of why rabble must be a moving and painful problem (bewegend und quälend) not only for modern bourgeois society, but indeed for any attempt, such as Hegel’s, at giving a reasonable (vernünftig) description of it.

The social problem of the Pöbel, to Hegel, is that they refuse mediation (Vermittlung): they refuse to work for money (the economic Vermittlung), they refuse to be taught anything, they refuse to think, they refuse, in short, all production of value. They just happen, unvermittelt (immediately). The Korporation, an instituted attempt at mediating, will fall short because the Pöbel remains, in consequence, unvermittelbar: its alterity cannot be grasped. It cannot be known (it is the unkown remainder).

And the problem of a reasonable description of society is thus the following:

What if there is only, or almost only rabble?

What if a description of society suffers the same fate as the Korporation – that it is haunted by its own remainder, a remainder that consists precisely in the (economic and/or semiotic) poverty of those it does not know; and of which it cannot tell even the size (it knows precisely nothing about them except that they might exist).

That they are in some way hidden, buried; part-while-not-partaking, present-as-absent; negating and negated; but there.

The problem of the ökonomische Tatsache or the fait social: they presuppose some sort of metonymic continuation between themselves and the web into which they are meant to lead: there must be an Ökonomie or a société to which they are the door. But behind might be worse than a labyrinth: there might be nothing. It might be a picture of a door painted unto a wall.

The problem of the truly, because necessarily silent majority: of an impenetrable deafness on the other side, of a stubbornness, of a refusal to produce anything of value, of an interpretative numbness, and an unreadability, far surpassing in size the small layer of sense one holds before the eyes – the rest of the iceberg, of which one does not even know whether it is still iceberg or something else entirely.

A silent majority that resists description without the describers even knowing that (or in what shape) it exists.

Indeed, beginning with Hegel is beginning pretty late: Roman Widder, in his excellent study Pöbel, Poet und Publikum (2020) has shown how 16th-century descriptions of society already identify Pofel (rabble) as a danger to established society: the mass of the lazy, deaf, greedy, property-less, vagrating, stubbornly refusing Bildung as well as Arbeit.

Impossible to disentangle the social problem diagnosed from the epistemological problem of diagnosing it: the investigation into social sense-making must inevitably fall short viz. those who simply refuse to make sense – they are its remainder, and as the source of epistemic frustration, objects of moral aggression.

And impossible, further, to disentangle this qualitative problem (interpretative silence) from the quantitative: what if most of social activity does not make sense? What if the majority is silent, what if most of society is nonsense? Is this worry, admitted or not, not part of the equally early sociological interest into mass – almost from the beginning under forensic auspices, almost from the beginning convinced that the mass is something unruly, possibly a priori criminal (Scipio Sighele's La folla delinquente: studio di psicologia collettiva of 1891, Gustave Le Bon's Psychologie des foules of 1895, Gabriel Tarde's L'opinion et la foule of 1901; the first and the last written by a criminologist, Le Bon's by a medical doctor)? Are they not haunted by the question: what if rabble-ness is a function of quantity – what if sheer majority makes people silent, sheer mass stops sense?

What if the problem of rabble and the problem of mass are the same?

What would this mean for a description of society, if society means, in some way 'a lot of people' and sociology 'the study of how they produce sense'?

And of course, to prescriptive social study, this problem was (and is) even more urgent: what is silent to description, is deaf to prescription. What if there is no working class? What if there is a working class, but it refuses to listen? What would be worse? What if the vanguard (party) drones on, emptily, in front of a deaf mass, making sense in front of that which refuses sense?

Methodological answers to this slightly crudely formulated worry have been varied: restricting oneself to extremely hedged and limited scientific claims was one possibility, admitting a base agnoticism via 'most of society and its workings', abandoning the question of size altogether. Putting the production of sense as a liminal goal was another – to say that, descriptively, one can conceive of a description thick enough that even rabble makes sense (we've just never found a description of such extreme thickness, but we might, in the future, if we really try); or to say that, prescriptively, there is a class, it just lacks consciousness for the most part (the majority) now, but we might, in the future, raise them into sense, into an understanding of itself and its relation to others, if we really try. But just like the Korporation and the Polizei, Notrecht and Colonialism, this does not make rabble disappear, it just shuffles it about.

And then there were the extreme reactions.

One way was to give society an abstract reality: society exists, but there are no people in it. (Luhmann's approach, for example). There are simply no members of society, thus no majorities, neither speaking nor silent. There is organized sense-making, but that sense is not made by human beings.

And the other way was to deny the reality of society: people exist, but there is no society. (The libertarian approach, for example). There is no organized sense-making in the first place, and every claim to the contrary is proto-totalitarian (is ready to enforce a totality where there is and can be none).

Both approaches pushed the rabble-problem further away, but without solving it. The second approach is generalized Polizei, always-only-spontaneous order requiring spontaneous defense, always-easily bordering on something gehässig. As for the first, Luhmann's late remarks on social exclusion are telling in this regard:

"Zur Überraschung aller Wohlgesinnten muß man feststellen, daß es doch Exklusion gibt, und zwar so massenhaft und in einer Art von Elend, die sich der Beschreibung entzieht. Jeder, der einen Besuch in den Favelas südamerikanischer Großstädte wagt und lebendig wieder herauskommt, kann davon berichten [...] Es bedarf dazu keiner empirischen Untersuchungen. Wer seinen Augen traut, kann es sehen, und zwar in einer Eindrücklichkeit, an der die verfügbaren Erklärungen scheitern." (Luhmann, "Jenseits der Barbarei", 1995)

Stepped down from the cold and inhuman heights of system theory, Luhmann's confrontation with the "part sans part" comes, crucially, with a simultaneous methodological surrender. The misery of the rabble is a misery "die sich der Beschreibung entzieht" (is indescribable), but that at the same time requires "keine[] empirischen Untersuchungen" (no empirical investigations). "Wer seinen Augen traut, kann es sehen" – the phenomenon is immediate: unvermittelt, and descriptively unvermittelbar. Equally crucially, not only the misery of the rabble goes beyond what can be described, but also its size: "und zwar so massenhaft", Luhmann writes, in a formula that, although found within his sentence, is nevertheless 'without grammar' ("so massenhaft [...] die sich der Beschreibung entzieht" doesn't add up). The formulation of the size is a grammatical remainder itself. The mass of the rabble, in its deafness and its silence, goes beyond what the sociologist can theoretically or grammatically express.

In his À l’ombre des majorités silencieuses ou la fin du social (1978), Baudrillard identified the massive silence and deafness of sociology's remainder – of the mass-rabble, the rabble-mass – as their mode of resistance. In contrast to the situationist interpretation, to him, the masses were not held in passivity by the incessant 'spectacle' of consumerism, alienated from their true desires, but instead showed 'defiance' by hyper-conforming to the spectacle.

Once again, it is not a question of mystification: it is a question of their own exigencies, of an explicit and positive counter-strategy - the task of absorbing and annihilating culture, knowledge, power, the social. An immemorial task, but one which assumes its full scope today. A deep antagonism which forces the inversion of received scenarios: it is no longer meaning which would be the ideal line of force in our societies, that which eludes it being only waste intended for reabsorption some time or other - on the contrary, it is meaning which is only an ambiguous and inconsequential accident, an effect due to ideal convergence of a perspective space at any given moment (History, Power, etc.) and which, moreover, has only ever really concerned a tiny fraction and superficial layer of our "societies." And this is true of individuals also: we are only episodic conductors of meaning, for in the main, and profoundly, we form a mass, living most of the time in panic or haphazardly, above and beyond any meaning.

Sense is produced in abundant quantities, Baudrillard argues, everyone is urged to produce sense, to make sense(s) – and the masses resist this urge in what could be called a semiotic strike. They simply participate, deaf, alien, and silent, in the spectacle. They indulge in an absolute rabble-ness, in their being outside to what bourgeois sociology and activist politics could grasp.

What is terrifying about the masses as they indulge in the spectacle, just above or just below or just outside meaning, one could paraphrase Baudrillard, is not only their abyssal deafness, but also their harrowing, hollowing silence.

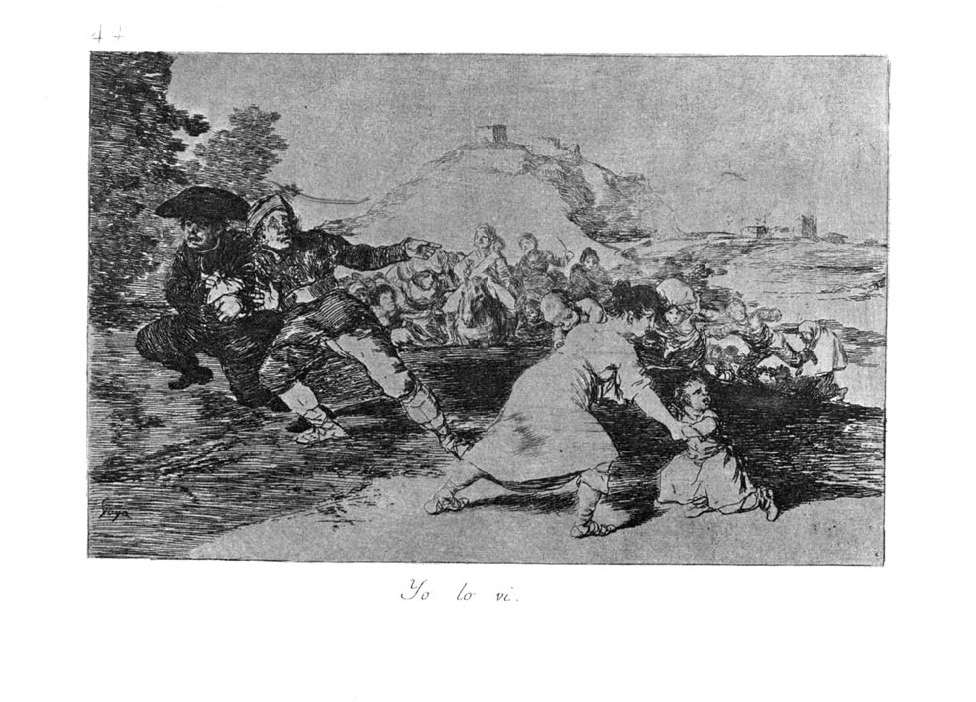

Of course, one can imagine Goya painting the Entierro and thinking: This is what you celebrate, you dumb fucks? Do you not see that there is no sardine? Is there any grey matter behind those stupid masks, is there anything you realize except this trivial feast pseudo-generously afforded to you by someone betraying, suppressing, hurting, and killing you; the illusory toys handed to you by Big Father Of Control? Did none of you expect the Spanish Inquisition?

But then, he is El Sordo ("The Deaf"), after all; and it is maybe this deafness that draws an ambito to enter, and a silence to plunge into.

YOU HAVE LOST

ITEM (1)

ABILITY 1x HEARING