Clipped Essaym III: Si es Goya

But make no mistake, this is not only Goya the grumpy ogre critic trashing his fellow Spaniards and fuelling la leyenda negra with both of his green paws – this is also Goya the pleasure-drunk ogre joining the mad dance and celebrating the paradoxical feast that is a burial (in general) of an absent non-sardine symbolizing an end of austerity at the moment of the actual beginning of austerity (specifically) – this is Goya joining in the obsequies of carnival and celebrating that there will never be another celebration, but that this celebration, in turn, will know no end –

this is Goya going like

HOLY SHIT GUYS THERE IS NO SARDINE

– well, maybe not to that extent, but it is important to note – and Goya scholarship has often done so (yes, don’t worry, I’ve read some) – that Goya’s gaze is characterized by an enormous empathy especially for what one lazily calls the ‘outcasts’ of society, for the drunks, the disabled, the imprisoned, the impaired, the stupid, the mentally ill, etc. And often, this is associated with his deafness – Goya, standing aside, disabled, feels sympathy for those who, in ways, share his fate.

Yes, especially compared to his greatest predecessor, Velazquez, who can pitch-perfectly channel icy disdain, infinite tenderness, or stately respect, it is much harder to decide whether Goya approves of what he paints or not, and I think it is indeed impossible to identify either pure disdain or pure support for what he calls El entierro.

But this indecision alone is not what lies at heart of Goya’s alleged empathy. For it is one thing to say that, for example, the mentally troubled deserve humane treatment, but it is an entirely different thing to enter the ámbito of their desires. Both require empathy, but to a completely different degree, or of a rather different kind. I would like to say that the first is so easy that it is self-evident, but both history and the present show that it isn’t. And it is very important to be capable of the first without the second. But the second one is exceedingly complicated in and of itself.

As it touches the question of being just below judgment.

Now, I’d argue that Goya’s famous empathy is famous because it primarily excels in the second way (this view is weirdly supported by a strand of art history who considers Goya one of “the first moderns” because he supposedly realized the proximity of genius and madness, that, in other words, the artist is like the mentally ill and the mentally ill are like artists: but no, you morons, that’s not at all simply the same thing; let me tell it to you in Lorca’s words: No quiero decir, sin embargo, que todas las mujeres que la cantan sean adúlteras; pero sí que, sin darse cuenta, entran en el ámbito del adulterio.). In other words, he is exceedingly ready to not only support, but also participate in desires, to enter their ámbito.

So the impossibility to say whether Goya approves of the burial celebration or not is not simply due to an indecision on his part, but more essentially due to the fact that he is sharing in the heap of desires unfolding in front of him – Goya is not only painting what he sees, but what theysee.

As if complicit with even the most disturbing undertone of the feast.

(If this were a different essay, I would say that this complicity is what makes him such an important predecessor of Expressionism – indeed, El entierro de la sardina might quite precisely mark the instance where the Baroque and Expressionism shake, as it were, their grotesque and majestic hands: Velazquez meeting Ensor. But I’m not writing that essay.)

This also means that the much-liked notion of the ‘empathy with the outcasts’ is slightly amiss; rather, Goya is very much able and willing to participate in desires, but also (at least to a degree) to choose in which ones – like Lorca does not jump on any random desire and lets himself be taken away, but chooses precisely the ámbito of (poorer) women, whose desires he deems politically interesting, and follows those. ‘Women’ are not simply ‘outcast’, but disenfranchised – they are part of society without full access to its advantages, but with a few added disadvantages in turn – and similarly, the festive crowd burying the sardine is hardly a heap of ‘outcasts of society’; rather, and crucially, they are society.

the mob built the walls, the streets

Much more than the bunch of degenerates, Goya seems to say, that make up the Royal family.

Doubtlessly, the entierro is a much more dynamic site of production than the decrepit stasis of the Royals. In the former, a palpitating rhythm secretes sociality, vital to the point of obscenity; in the latter, sociality comes to die in a dusty room full of mannequin-like humans with vacant stares. The third person from the left, by the way, the young man who’s decidedly getting worn by his blue clothes rather than the other way around, is the future King Ferdinand VII, the one who will re-allow carnival and re-install absolutism.

This is not anarchy vs. the state, by the way, the entierro depicts an array of social roles (of masks and costumes) and thus of social strata, not a nondescript and identity-less multitude alien to all notion of authority, right, or violence; while conversely, the Royal family is so profoundly out of order that they couldn’t possibly establish any. Not for the unlife of them.

It is, rather, a differentiating between states of reality: between the reality of the entierro and la familia real.

For it is fully possible that the burial of the non-sardine is a requirement of their interaction.

And in order to leave that possibility open, it is necessary to do what Goya does in the entierro, namely to stay so, so far away from touching that Realism switch, coincidentally making it impossible to say whether the people on the painting are masked or, maybe, not.

So I think it is very important, when thinking about surrealism, to note that it was fully possible to paint that Goya painting through nothing else than a study of popular desire, formulated here in dance and costume rather than rhyme and melody – to not invent monsters, but to discover them in the web of social reality, as products of a swarm imagination, as stereotypes, as masks, and as fact; and to put El entierro de la sardina, surely a title every self-respecting surrealist dreams of, as a purely descriptive title.

Thus, it seems to me that El entierro de la sardina holds a truth that was, at some point in the 20thcentury, or maybe even earlier, kind of lost.

Which is that, if surrealism has to do with popular formulations of desire, there is always the risk that any singular individual high-art artwork, almost no matter its quality, will be simply, nonchalantly, and utterly overtaken by any dynamic that is a dynamic of the market.

This is not about the work of art as an individual and singular metaphysical event being reduced to a commodity. Rather, my point is that any commodity tends to be a much better surrealist object than any artwork, precisely because the artwork is, at worst, the product of only one individual imagination, whereas the commodity is intrinsically composed of multiple strata of horizontally distributed and vertically layered, intense and contradictory desires.

Surrealism doesn’t happen in ateliers, but in supermarkets.

Or let me restate the problem: No figment of a Jungian archetype or a personal trauma you might find way, way down in the cellars of your biography could ever be an index or a manifestation of a more complex, abyssal, beautiful, and disturbing desire than a successful advertisement, an urban legend or a meme is. As any desire derived from individual experience is only limitedly repeate- and shareable (it’s private, duh), it is, from the viewpoint of scientific surrealism, absolutely uninteresting.

To claim something different would mean to spit down on popular desire with an arrogance that is real rather than surrealist.

It means to differentiate between manifestation of desire not on grounds of how shared the desires are, but how high the price tag for the manifestation is (artworks express more than commodities because they’re more expensive). That’s also a nice way of thinking about all of this, of course, but it’s not surrealist.

Recall Breton’s slogan in the Manifeste du surréalisme

Fiez-vous au caractère inépuisable du murmure.

Commit yourself to the inexhaustible character of the murmur.

Is anyone thinking that the inexhaustible murmur is the expression of any individual? With a name and maybe a trademark moustache? Isn’t this, rather, the murmur which re-appears in Foucault, when he assembles a massive attack against the single authorial figure, instead aligning himself with those discourses that se dérouleraient dans l'anonymat du murmure, that unfold in the anonymat of the murmur?

This, I’d argue, is one of the major tensions animating Goya’s art: The advent of scientific surrealism, with its concomitant commitment to the swarm and the murmur, in the midst of the life of a celebrated court painter and portraitist.

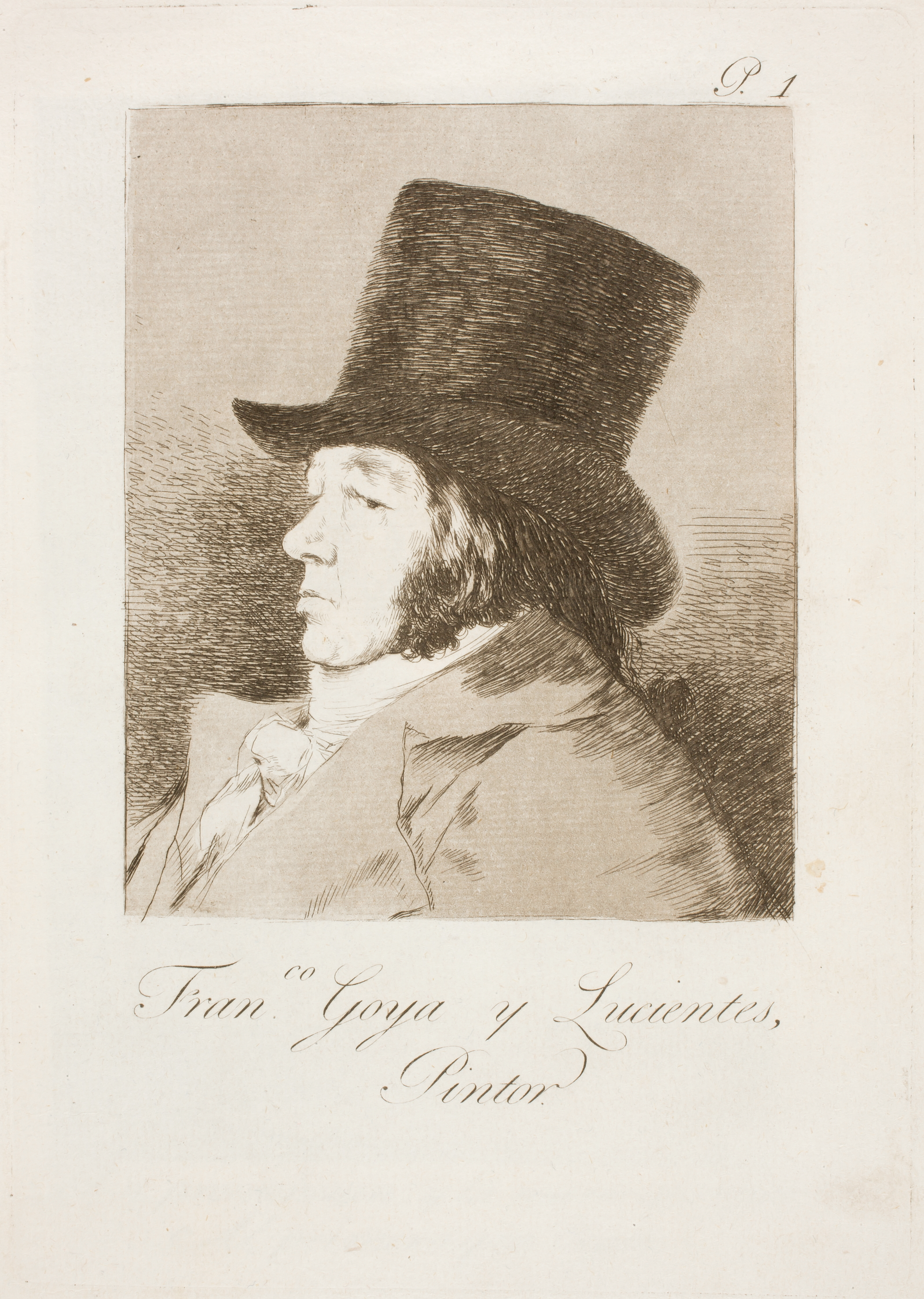

Yes, Goya does his best to share in the glorious, sense-drunk anonymat of the entierro. But simultaneously, he is fully aware that something keeps him from their feast, lessens him in their multitudinous eyes: his top hat of a name. Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes.

This, of course, is what keeps him from the anonymat. This is the present non-sardine, the sardine that is a sardine by name only, but by name proper: his proper name.

Yes, he celebrates the entierro in all ways accessible to him; he celebrates the nameless swarming desires that palpitate in the dancing mass as if pointing at them and saying: this here is power (puissance), this is what rightfully belongs under the sort of emperor sky Titian invented for the monarchs of a different age.

But he does not appear, himself, in the painting. It’s not the group on El entierro that includes the painter.

It’s the royal family.

La familia de Carlos IV is not just a brutal takedown of bankrupt authoritarians, is it also a portrayal of the doglike attachment of the author to those authoritarians. It’s not only a sendup of power-holders, but also, and maybe even more mordantly, of the complicity of artists in the establishment of that power (pouvoir) – if Goya’s painting somewhat looks like a sad and tired parody of Velazquez Las meninas, that’s because it is:

While Las meninas had been both a major document and factor for the recognition of painting as real art (a recognition only the power-holders could afford), La familia de Carlos IV is like saying: Well look how that turned out. The painter stands behind his easel, in the shade of his own canvas and the two massive paintings already hanging on the wall and, finally, the shade thrown by the decrepit wax-figures cosplaying a different era.

Outside, somewhere, they’re burying the absent non-sardine. You can almost hear the bass.

Just below audible frequency.

YOU HAVE RECEIVED

TEXTS (1)

ANDRÉ BRETON: LE MANIFESTE DU SURRÉALISME

ITEMS (1)

FOOD 1x ALMOST AUDIBLE BASS