Artifical Osman Spare

When the time will have come to truly begin the self-mystifying part of my own life, I will tell everyone that in my youth, having just returned from the murs de poussière of Northern Africa, I used to study in an old, often fog-covered European lakeside town near the Alps, under a professor specializing on the esoteric and the occult.

And when the will have come to add a bit of clarity and honesty to the myth, I will be forced to admit that I never really cared for the occult and the esoteric, with very, very few (and superficial) exceptions.

One of those exceptions was the work of Austin Osman Spare (1886-1956), a British occultist and artist (writer and draughtsman). AOS for short, he was involved with Aleister Crowley himself, yet had a falling out with that big elder statesman of British occultism because AOS had no patience for the hierarchical structure Crowley's order championed. He later became friends with one of my favourite weirdos of the 20th century (and another of the aforementioned exceptions), Kenneth Grant, who spent a good part of his life cataloguing all 'existing' demons – a wild synthesis of classic Western esotericism and occultism, H.P. Lovecraft's fictional universe, Jewish mysticism, Vaudou, and his own additions, and including manuals on how to summon them. AOS designed a tarot set and a card set to divine horse racing outcomes with, he wrote a few tracts (every occult must write a few tracts, it seems), developed numerous short-lived theories about the cosmos, very briefly editored an art journal called "FORM" (that's where my interest started) and argued for what he called "atavistic resurgence" – I'm not going to explain that one, but this was the second thing about him that piqued my interest.

And, of course, he drew. That was the third thing that made me vaguely interested, because I guess I do really think that the greatest aspects of occultist activity are the aesthetic ones. In short, occult thought sometimes makes for great art, such as Kenneth Grant's ridiculous neologisms and ominous titles – or such as Austin Osman Spare's drawings.

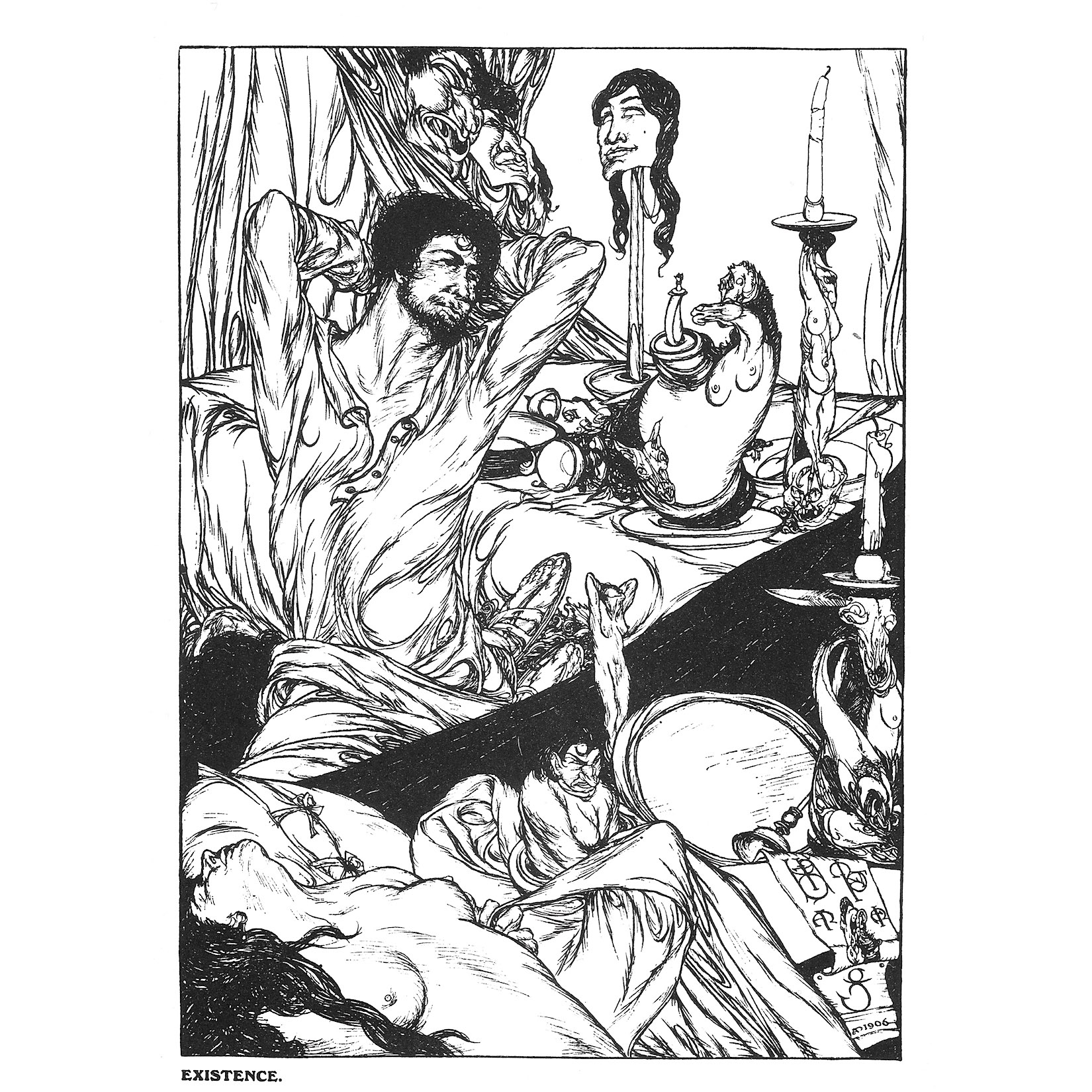

In his most famous phase, AOS practiced a style reminiscent of high-time art nouveau drawing with its sinuous lines and mythical imagery, especially of Aubrey Beardsley's style with its virtuoso craftsmanship and satiric bent. Drawings such as The Argument illustrate Beardsley's influence most clearly:

Just like with Beardsley, I find it hard – as someone who's drawn a fair amount of stuff themselves – to not at least admire the sheer craftsmanship of this style, more precisely: by the absolute confidence of those lines. I suppose that everyone who's ever been at least somewhat committed to drawing will be able to tell you that drawing is very much about confidence and doubt. It would almost be possible to characterize drawing styles according to their relationship to doubt: some styles encapsulate doubt and 'remain' searching; other styles work to eliminate it altogether (or, more exactly I think, to raise or lower it to a different level without ever eliminating it). Beardsley is an absolute champion of the confident line as it punches through space like that famous "train qui jamais ne s'arrête [...] parcourant la blanche immensité d'un hiver eternel". And so is Spare, and it would be hard to tell whether the confidence of someone who is ready to give his ever-changing, always-offbeat theory of the cosmos as a whole spilled over into the confidence of a master draughtsman or the other way round.

But what is funny about Spare, what is funny about him in the year 2024, is where his Beardsley-like style derives from Beardsley. Even when Beardsley's scenes get very crowded, such as in The Cave of Spleen, he is absolutely meticulous about the come and go of his lines:

I will bet about fifteen of Kenneth Grant's demons that you can follow every single one of these lines and trace where it starts and where it leads to, and make (visual-logical) sense of it. Beardsley's drawings can get crowded and are almost always grotesque in some sense of that word, but they pride themselves in the visual severity they impose on it – what binds them, truly and thoroughly, to a Modernist aesthetic after all. Spare, on the other hand, goes into quite a different direction. His lines, confident as they are, are a shadow of a doubt pertaining to "where from?" and "where to?". There are mild forms, such as the head of the creature this guy is dancing (?) with, where some pretty solidly weird folding is going on, but which remains somewhat visually stable:

And then there are more 'severe' forms, for example this:

What exactly is going on with what might be the torso's right arm?

And then, there is hardcore stuff, where the visually consistent objects seem like islands in a tempest of abstracting forces and icomprehensible lines, such as Existence.:

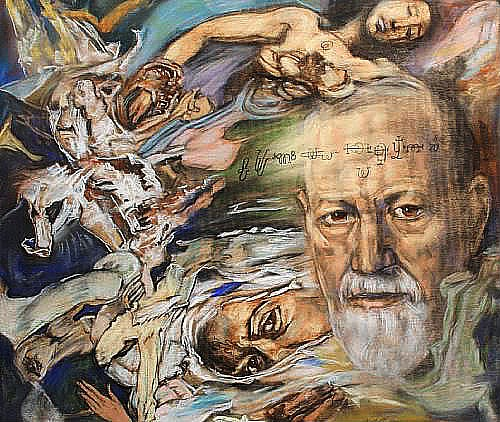

Or, for that matter, the Portrait of Sigmund Freud:

And why is this funny, or maybe even interesting? Well, because when you look up AOS pictures on google, you will find that a substantial part of the results are concerned with AI prompts 'about' Spare (such as: "xyz in the style of Austin Osman Spare", or simply "Austin Osman Spare painting/drawing").

Now, what happens as a result of those prompts?

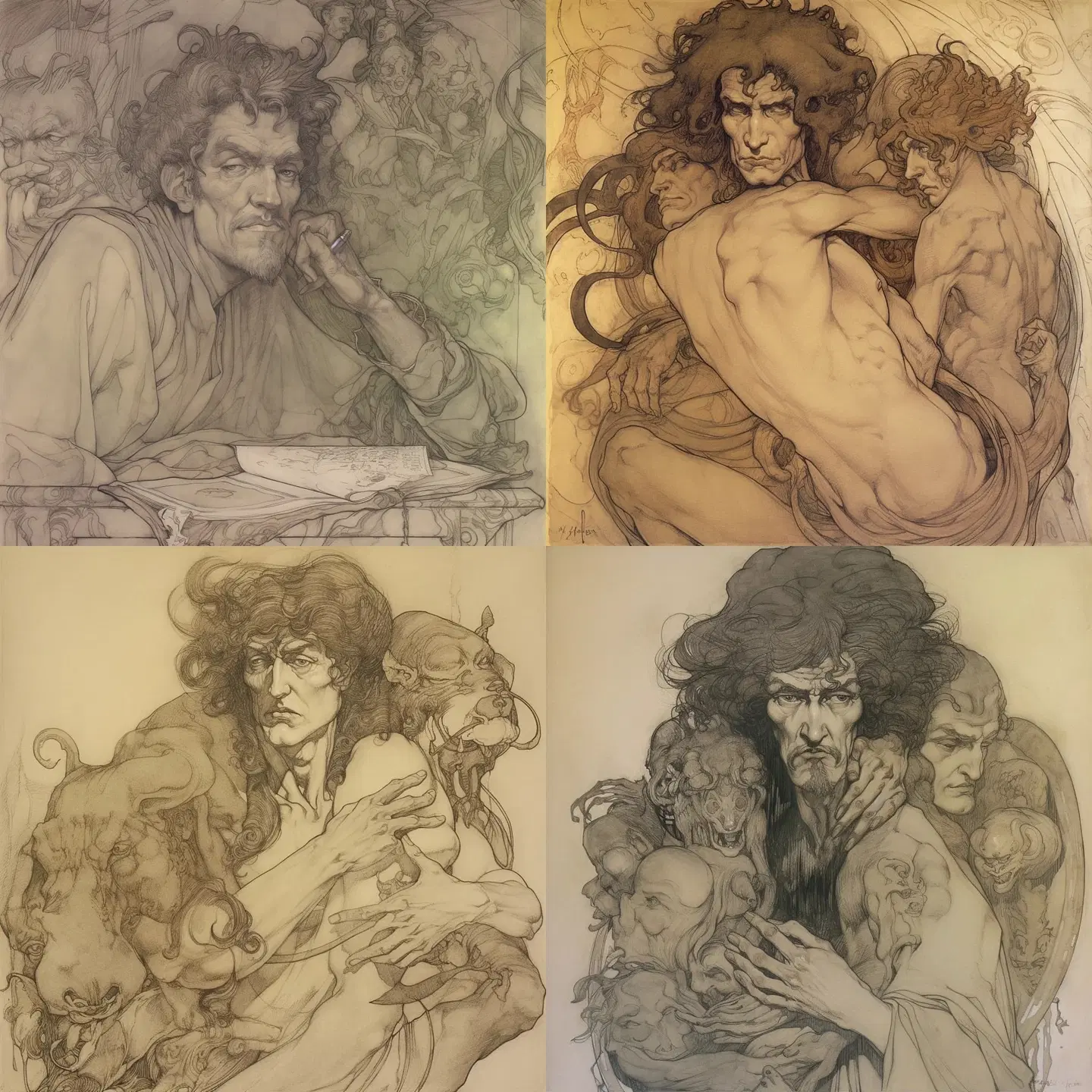

An overview in the Midjourney library shows a progression: Midjourney generations proposed varying interpretations of "Austin Osman Spare painting", starting with quasi-portraits of Austin Osman Spare with what I would call a heavy anime-tendency:

After this Castlevania-channeling phase, Midjourney V.3 and V. 4 presented rather boring portraits of the guy before V.5 got to the real shit:

This, finally, was a new reading of the prompt: this was "Austin Osman Spare painting" visibly in the double sense of the word: A painting of Austin Osman Spare in what looks like an emulation of his style. (And a massive chad-ification of the artist at the same time).

V 5.1 and 5.2 continued in that vein, before V. 6 went into a different direction, now more decidely symbolistic in nature, abandoning some of the art-nouveau inflection of V. 5 in favor of what looks like 1940s or 1950s fantasy illustration and finally also a goth-component that got even more pronounced in V. 6.1., where Austin Osman Spare somehow completely turns into The Crow, complete with a folding-back of AOS' proper style into a US comic book approach:

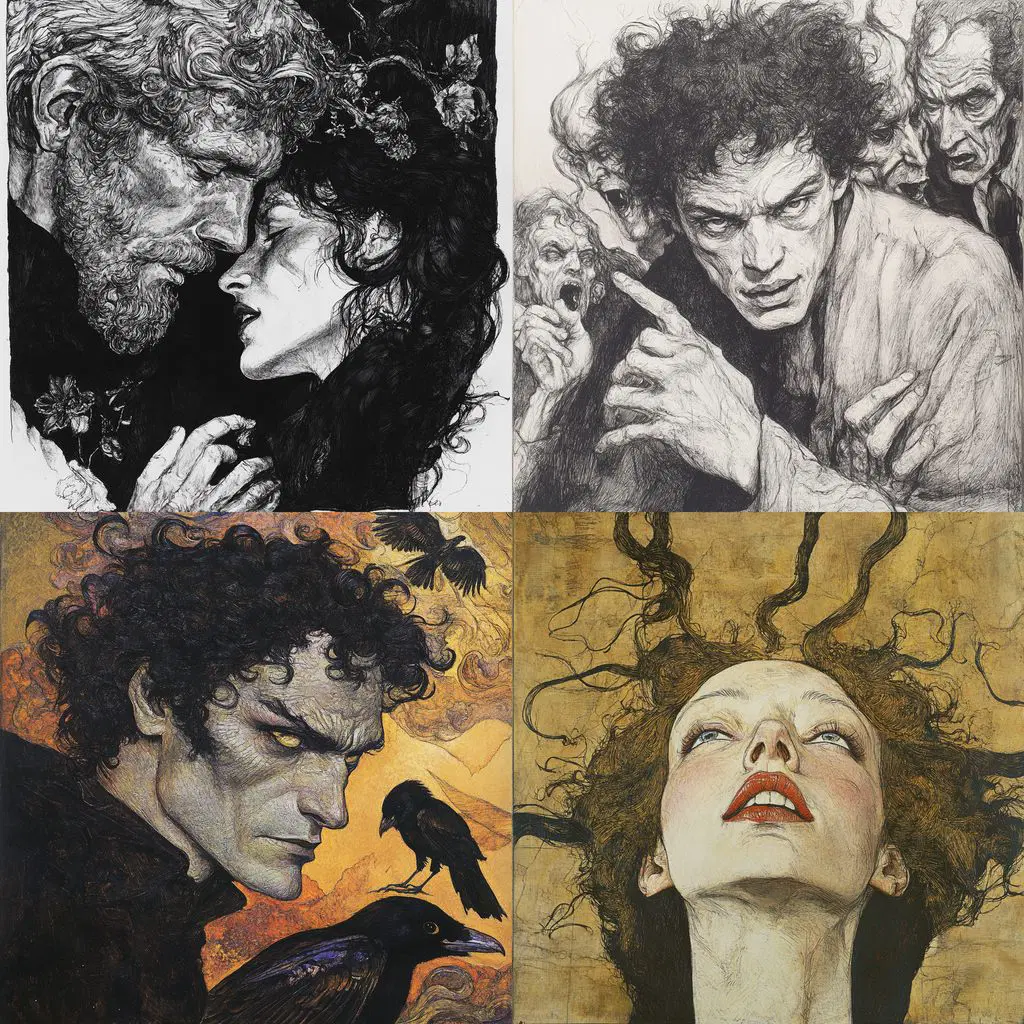

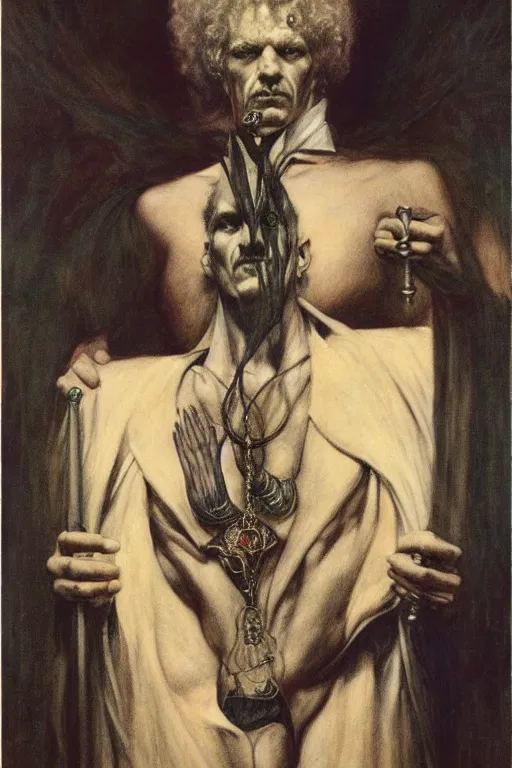

But it is Stable Diffusion that offered one of the most intriguing suggestions, following the lovely prompt "occult art portrait of austin osman spare by austin osman spare"

Now on first sight, this doesn't look anything like an Austin Osman Spare drawing and much more like darkened William Blake, except, of course, the line work. Much like in Existence. and other AOS works, visual consistency is something that occurs from time to time, but is in no way an unconditional characteristic of everything depicted. And of course, this is true of the Midjourney V.5 pictures, too.

And you might say, why, yes of course, this is true of all AI art, at least in its current state. But this is where it gets funny: it is true of AI art, but it is also true of AOS art. It is true of both in such a strong sense that Midjourney V.6 looks less like Austin Osman Spare's style because its visual consistency grows compared to his own work. AOS lines are precisely not as thoroughly intelligible, which makes V.6's propositions, in turn, go into the direction of more recent fantasy illustrations.

What I find funny or interesting about this is that it shows that maybe AI (in today's state) actually has a style, a style in the strong sense: it is wholly distinct yet distinctive aspects are shareable. Austin Osman Spare, for example, shared some. This is very different from the now almost-canonical view of AI art as primarily deficient, either in a crude pictorial sense (AI cannot depict reality, for example because it cannot uphold visual consistency – but neither do AOS drawings), or in a pragmatic sense: it is treated as a tool devoid of style and in need of it, in need of the input "abc in the style of xyz". But maybe 2023 and early 2024 AI had its own style, and it shares many similarities with Spare's. Visually consistent objects caught in a storm of visual inconsistency. Private lines coexisting with free lines, working lines coexisting with striking ones.

Spare was convinced that his lines were tracings shared with a (humanly fully accessible) higher form of intelligence (see: The Book of Pleasure). Art history was convinced that his take on non-figurative art (not ever truly abstract, but never fully representative) sucked. It didn't break up the figure in any theoretically sanctioned and reasonably sound way (like Duchamp or Gris), it didn't abandon it altogether (like af Klint or Malevich), but it wasn't some strange and lovely late bulwark of the classic figure (like Magritte or Modigliani), either. And moreover, it wasn't intelligent (like Klee). From all established art directions, it was maybe closest to Max Ernst. Like Ernst, it kind of went nowhere (in fact, it went even less anywhere, maybe because it is a lot less decorative than the somewhat painterly Ernst).

What Spare claimed and AI knows, and art history only sometimes realizes, is that nobody knows what memory contains.