Abstracat

for V.

"The cat program is a popular problem."

Some ten years ago, I shared an apartment with, among others, a student of IT. Once, he brought home stray homework from his programming class. The task basically consisted of coding a cat, that is, of designing a program that would fulfill the cat-function. The cat-function, in turn, was defined as – if I remember correctly – the ability to be asleep some of the time, awake for the rest of the time, to meow at irregular intervals, and to spend some of the time awake 'playing with a ball of wool'. Maybe some other stuff I have forgotten about, but it was certainly quite a short list. Now, the goal was to design this cat as efficiently – with as few lines of code – as possible, and to make it run 'as autonomously as a cat', namely without requiring input and without producing output (other than the 'cat' as a temporally distributed amalgmation of doing and non-doing). As an additional goodie for the cracks, you were allowed to widen the cat-function by adding other activities (say, licking its fur every six hours), but the goal remained to do it with as few lines as possible, with the designer of the 'shortest' or 'tightest' cat being awarded with some prize I can't remember. What I do remember is sitting in front of the computer with my former flatmate and a few of his colleagues, staring at the lines in front of us, frantically searching for opportunities to trim the virtual cat down to its most necessary lines.

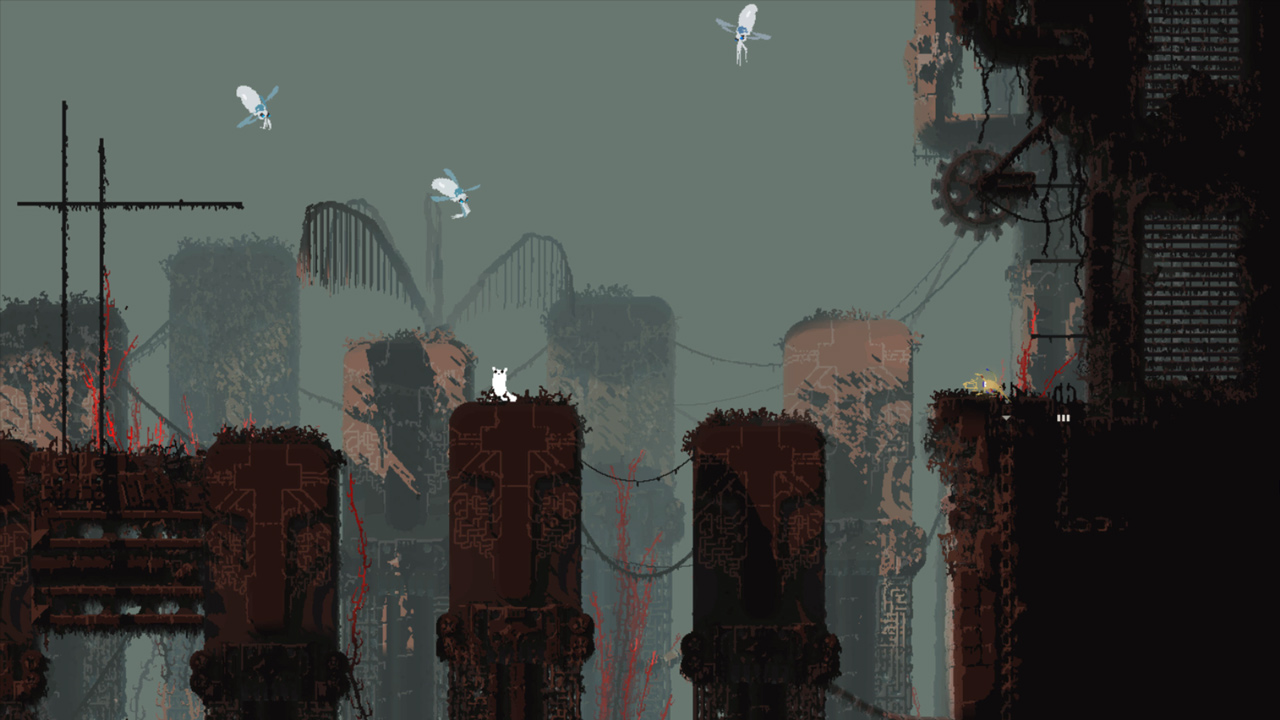

I was reminded of this when recently, I played Stray, after a recommendation from, of all places, the feuilleton of The Guardian. Stray is a video game in which the player assumes the control of a stray cat in what might be a post-apocalyptic world no longer populated by humans, but by a variety of animals and by robots, remnants of the anthropo-hegemony past.

While the story and the world etc. are charming and well-crafted, the main appeal of the game is very obviously the possibility to 'steer' a cat. All those parts of the game that are truly video-gamey in a stereotypical sense (entailing enemies, quests, combat, stealth, etc.) pale in comparison to those parts in which you're simply a cat doing cat-things ("press B to meow") in a world modelled after Hong Kong's notorious Kowloon Walled City. Allowing you to experience some yberpunk from below the waistline, or spinally horizontal cyberpunk, you walk across keyboards and piano keys, leave scratchmarks on virtually every expensive surface, snuggle up against legs, make robots stumble over you, or roll yourself into a furry bundle on some cushion and take a nap. Moreover, you make use of tubes and wiring and air conditioners and washing lines and buckets and what not to make the most of every verticality available, to impose a wholly different urbanism onto a city-structure intended for humans and their robots. Feeling the psychogeography of this Blade-Runner-y city transform under swift paws belongs to the best of what Stray has to offer, especially as it also allows you to realize that these 'futuristic' cities have become extremely familiar (with their neon, their slum-glam, their techno-orientalism, their incessantly wet streets) and thus de-familiarizable by Stray's feline viewpoint.

At the same time, the cat protagonist (of unspecified name and gender) never has to eat (althought it can drink), never has to sleep, never has to pee; all these aspects of a living cat are trimmed away. Stray's cat has no needs at all (just like the cat of my flatmate's homework, once running, they require no input). Their world includes only things they are able or unable to do, but nothing that they must do. Maybe this is the game's strongest feat of defamiliarization: to insert into the post-apocalyptic terrain, or the cyberpunk dystopia, worlds so often defined by unfulfilled needs (economic scarcity and libidinal frustration), a being that has no needs at all.

"If you are a cat, it’s your duty to learn to program. If you are not a cat, but know someone who is a cat, please persuade them to read this book."

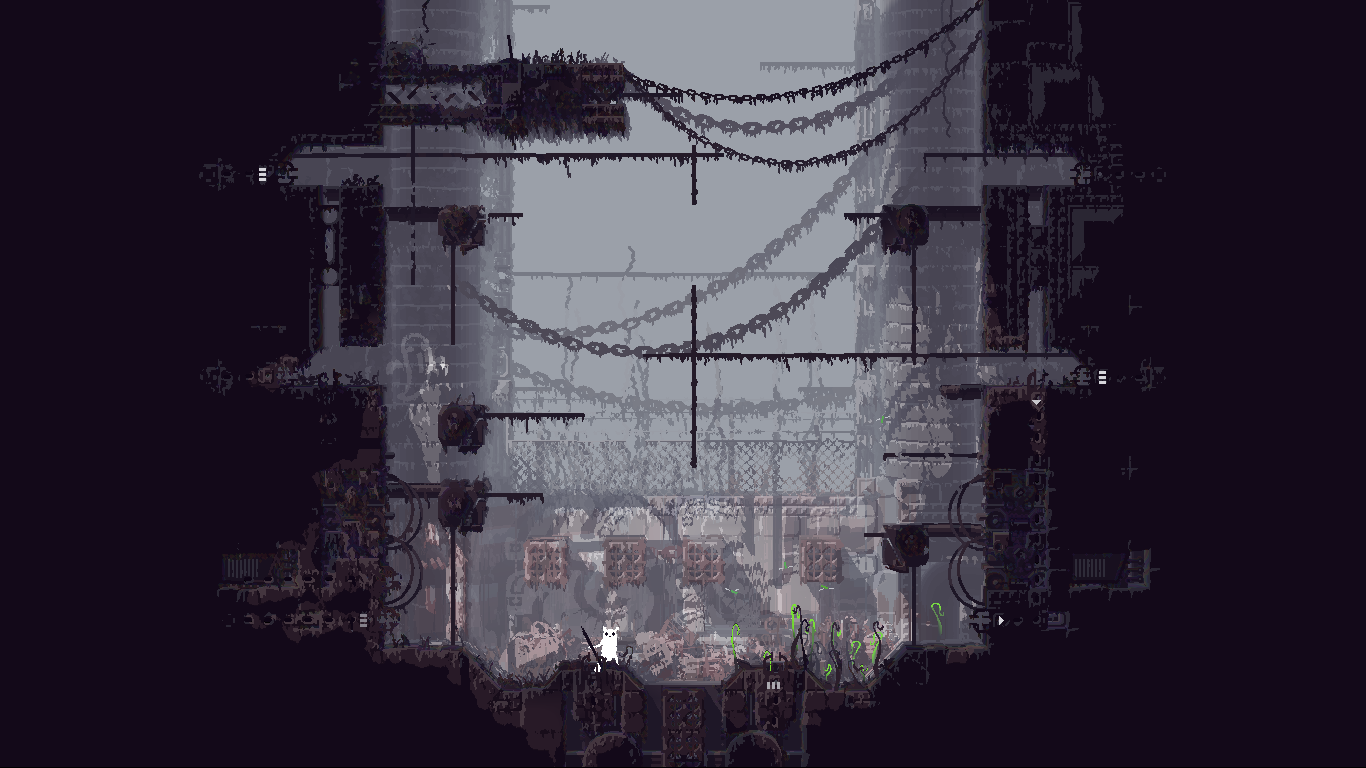

2017's Rain World had taken an in many ways opposite approach: its felid protagonist-creature roams its posthuman world not as if it were a playground, but driven by a set of fierce needs (food, shelter).

In Rain World, exploration is not a pastime, but a requirement full of fear and danger. Stray's protagonist is more or less outside of the food chain, Rain World's protagonist is somewhere on the lower rungs, and it shows – while Stray can be mildly frustrating at points, it is never, never difficult; Rain World, in turn, is brutally difficult, as you never have enough time for anything and every turn might be your last as you're devoured by a much stronger enemy you just happened to encounter by bad luck. Playing Stray feels like a walk in the park, with both the definition of 'walk' and 'park' extended to qualitatively and quantitatively very good levels; playing Rain World feels like a continued panic attack. Smaller creatures tend to have a higher heart rate, do they not?

But then the protagonist of Rain World is not strictly speaking a cat, but a member of the fictive species 'slugcat'.

Further differences between the two games could be named: Stray's world has no 'weather' (taking place almost entirely within a shut-in, as-if-subterranean world) and makes up a cute little ingame reason for the cyberpunk wet gleam on the asphalt, Rain World has, well, a recurring downpour that is all but lethal to the slugcat and must thus be avoided.

But, of course, what seems most towering is the similarity: the similarity of a feline story written (griffé) on a canvas not simply without, but after human beings.

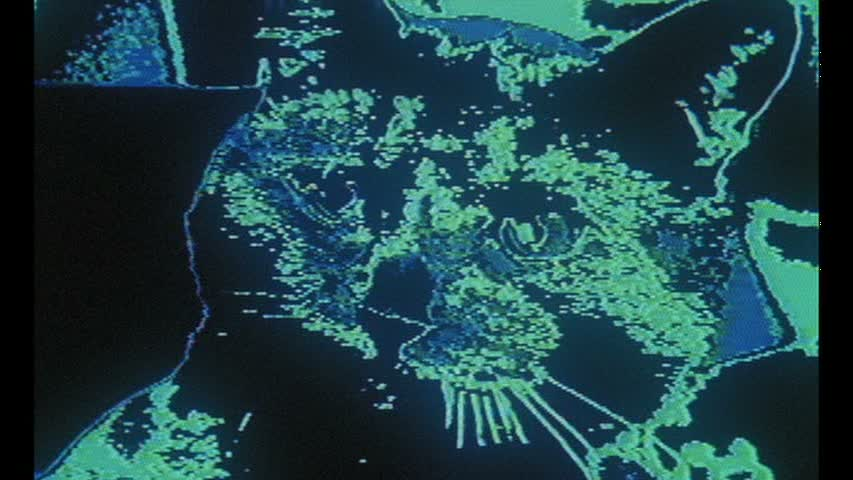

But Stray also reminded me of a film by one my of favourite directors: Sans Soleil (1983) by Chris Marker. Not just because the game takes place literally "sans soleil", seeing that it is completely underground, but mostly because Stray seems like a playthrough of Marker's prime obsessions (in no particular order): the future, the physical basis to the 'digital world' (wires, tubes, etc.), Eastern Asia, memory, and, of course, cats.

Cats of the organic, and cats of the non-organic kind.

In Sans Soleil, in a digression about Japanese video game arcades, we meet Hayao Yamaneko, who provides one of the film's most important concepts (the 'Zone'), and who is a programmer of 'synthesized images', that is, of technologically generated images, computed with an EMS Spectre Video Synthesizer. To please the narrator, the narrator tells us, Yamaneko would generate images of the narrator's favorite animals, among which features, prominently, the cat:

Not a really suprising move from someone whose surname is Yamaneko, "wild cat".

And not a suprising move in a film by a director whose part time alter ego, part time muse, happened to be a large cat, called Guillaume-en-Egypte or Monsieur Guillaume or Guillaume le Chat alternatingly, shown below with Agnès Varda:

And who also represented Chris Marker during his performance/presentation in Second Life (and the museum-island he had built ingame featured Guillaume all over the place):

Here, in fact, are Varda and Guillaume again, this time in Second Life:

Or rather, it's Varda's avatar (Vardatar?) dancing with a virtual cut-out of Guillaume, whose first (or second?) instantiation is probably in Egypt, and thus not here, in Second Life. Anyway, what is Second Life to a being that has nine?

"Video games are the first stage in a plan for machines to help the human race, the only plan that offers a future for intelligence."

– Chris Marker

Everyone must always recall and respeak Derrida meeting his cat (and his cat meeting him!) in the bathroom. In her contribution to Der Alltag der Dekonstruktion, Vera Thomann has performed a brilliant (if fiercely difficult) reading of the different theoretico-political strategies with which Derrida's famous bathroom-cat-encounter has turned itself into a cornerstone of (the philosophically inclined parts of) animal studies. An aspect of Derrida's text that might possibly be called recursive offers an entrance or a gateway ("Tor") into that bathroom-encounter, again and again –

"[D]er Philosoph begegnet seiner Katze, immer und immer wieder. Die Anekdote dient folglich als Tor zu dieser Erfahrung: Derrida führt die Pluralisierung und die Potenzierung von Kontingenz derart in ,seiner' Katze zusammen, dass ein Erleben davon entsteht, was es heißt, sich mit dem Tier zu beschäftigen."

The cat-encounter is thus the point in Derrida's text – the passage – that allows (and forces) readers to plug in, to plug into the argument and to follow (Derrida's pun: l'animal que donc je suis, the animal that I thus follow), it is where you boot up the program again and again ("immer und immer wieder"). Install the Cixous-mod or don't, speedrun it, re-read it with more knowledge and for the harder problems ("NG+"), the "Abstraktionspotenzial der Tierszene - das heißt der Kompatibilität ihrer Erfahrungswelt" will force, push, embrace you towards something that looks scarily like three dimensions, and produce a Second Life on the other side, a second, a ninth, an n-th. Kompatibilität, Komputabilität. Animot, Animoteur.

Conversely ("Im Umkehrschuss"), this signifies that, no matter how often you reboot, "jede Rezeption der Katzen-Anekdote die der Derrida'schen Theorie unterliegende These mitrezipieren muss, dass sich nämlich Jacques Derrida als erster Philosoph - und damit als Begründer einer neuen Diskurskategorie - mit dem Tier beschäftigt hat". If Derrida goes to lengths to deny that this cat-encounter is an "Urszene", as Thomann shows, this is obviously true insofar as it is infinitely replayable, as Thomann equally demonstrates, but at the same time, it is also true in a way the Derrida-program is – well, maybe not unable to think, but perhaps where it falls prey to the contingencies ("Derrida führt die Pluralisierung und die Potenzierung von Kontingenz derart in ,seiner' Katze zusammen, dass ein Erleben davon entsteht, was es heißt, sich mit dem Tier zu beschäftigen", my italics) of a memory that is only partially random access.

"J’aurais passé ma vie à m’interroger sur la fonction du souvenir, qui n’est pas le contraire de l’oubli, plutôt son envers."

– Sans Soleil

If part of a L'animal-que-donc-je-suis-playthrough, 100%, no bosses skipped, means to re- and re-re-replay something that is no Urszene in any second life, but a first in the first, namely that Derrida's game is the first philosophical game in which you can play the cat-encounter (as a stand-in for the animal encounter), this game somewhat conveniently 'de-remembers' an amount of ecofeminist scholarship (see also Susan Fraiman's work on the topic, whom Thomann quotes). But well, the tutorial to Derrida's game would answer, that's a question of genre (gender/Gattung), ecofeminists are mostly real-time strategy, whereas L'animal que donc je suis is obviously a First-Person Shooter (que donc je suis). You're simply not looking for the same thing. Ok, one might answer in turn, but Derrida's program also entails de-remembering that post-structuralism had already talked about the animal, had, indeed, talked about cats, back when it was still called structuralism; when Claude Lévi-Strauss and Roman Jakobson co-wrote an interpretation of Charles Baudelaire's "Les chats".

Les amoureux fervents et les savants austères

Aiment également, dans leur mûre saison,

Les chats puissants et doux, orgueil de la maison,

Qui comme eux sont frileux et comme eux sédentaires.

Amis de la science et de la volupté,

Ils cherchent le silence et l’horreur des ténèbres ;

L’Erèbe les eût pris pour ses coursiers funèbres,

S’ils pouvaient au servage incliner leur fierté.

Ils prennent en songeant les nobles attitudes

Des grands sphinx allongés au fond des solitudes,

Qui semblent s’endormir dans un rêve sans fin ;

Leurs reins féconds sont pleins d’étincelles magiques,

Et des parcelles d’or, ainsi qu’un sable fin,

Etoilent vaguement leurs prunelles mystiques.

- Charles Baudelaire, "Les chats"

This – Jakobson and Lévi-Strauss co-writing a text on cats-in-plural – is not an Urszene of structuralism; and Lévi-Strauss writing a text on cat-in-singular exactly ten years later (Histoire de Lynx; which will turn out to be a text about twins) is not the Schlussszene. But how does structuralism, here, engage with the cat problem, play the cat program? By pretending that the poem is an old, 19th-century house, half-ruined yet curiously eternal, or haunted by something that surpasses it, and then by following its haunts via the two feline axiis of smooth and silent spinal horizontality (what they call syntagm), a movement so soft and supine it might as well be part of the floorboard; and the rain drain climbing, latent in each put paw, that connects, with hidden abruptness, the floors with other, possible floors (what they call paradigm). The haunt is what follows from this intersection.

And by formulating this neat little cat-function:

L’Erèbe les eût pris pour ses coursiers funèbres,

S’ils pouvaient au servage incliner leur fierté.

Ils prennent en songeant les nobles attitudes

Des grands sphinx allongés au fond des solitudes

Shorten, I imagine my former roommates' teacher saying.

Erebos would have taken them as his dark messengers, if they weren't too proud to do it [...] They take, when dreaming, the noble attitudes of great, stretched-out sphinxes.

Shorter, I imagine my former roommates' teacher bellowing.

Erebos would have taken them as workers [...] They take the noble attitudes of sleeping mythical creatures.

Shorter still.

They refuse to be taken as active, because they take themselves as passive.

Is this a short formulation of the cat-function? Maybe at least as long as they're dreaming.